Pluralizing Narratives

24 October 2018

Magazine C& Magazine

7 min de lecture

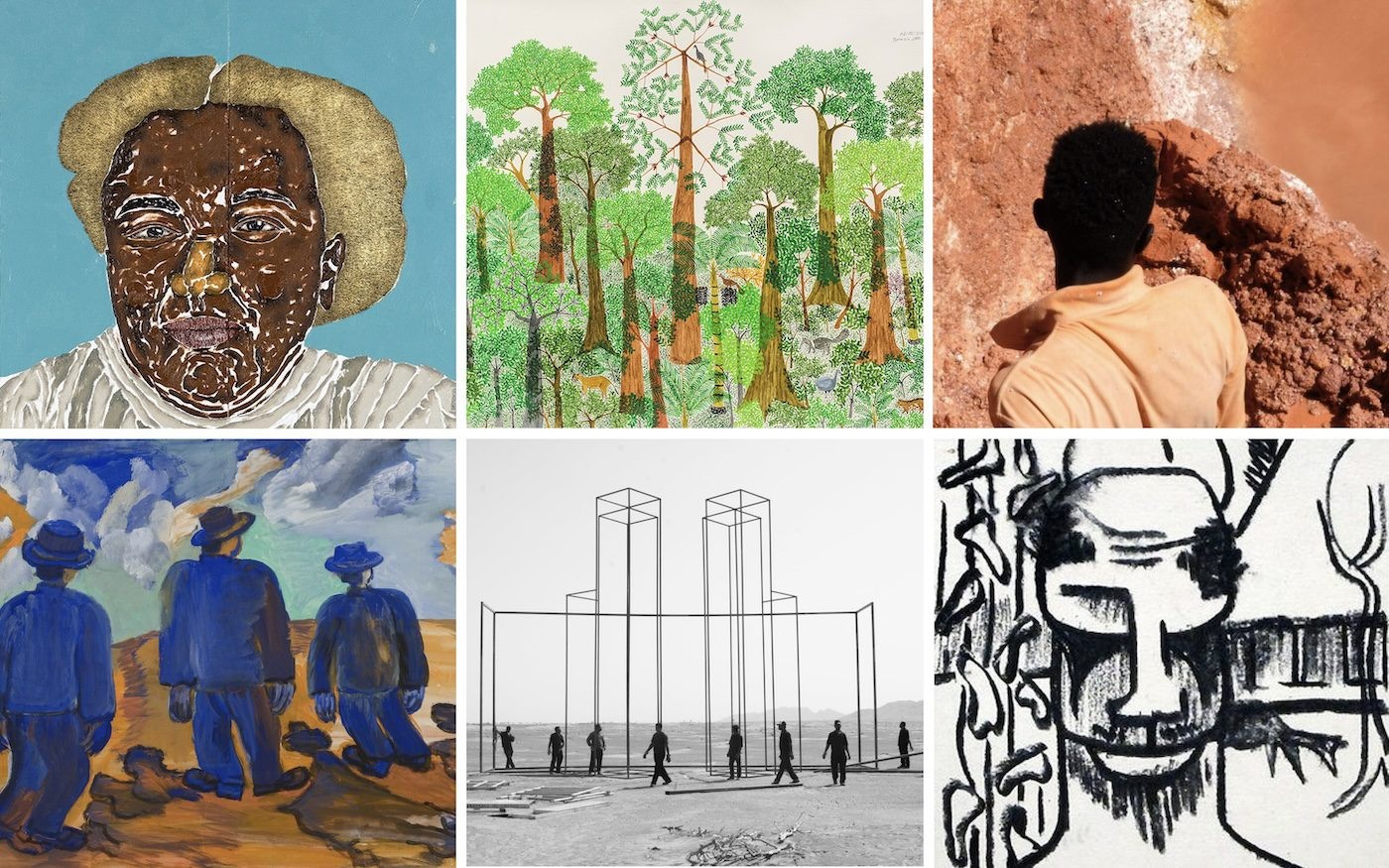

With 450 works by 214 artists and eight thematic areas, an exhibition at two of São Paulo’s major art spaces revealed a complex network of social relationships around art produced by Afro-descendants.

<div class="col-md-11 col-nopadding-mob">

In line with Adriano Pedrosa and Lilia Schwarcz’s curatorial rationale for Histórias Mestiças (Mestizo Histories), and focused on the abundance of material references to racial mixing in Brazil, the exhibition Afro-Atlantic Histories, revealed the complex network of social relationships in which an infinite number of historical and art objects circulates. As many private galleries and collections as public museums and institutions aided in putting together its multifaceted narrative, which by pluralizing the term history suggested a desire to escape the dangers of a single story.

Curated by Pedrosa, Schwarcz, Ayrson Heráclito, Hélio Menezes, and Tomás Toledo, a total of 450 works by 214 artists were on exhibit, spread between MASP (the Museum of Arte in São Paulo) and the Instituto Tomie Ohtake. With this grouping, the exhibition offered different cultural temporalities, without attempting to establish a chronology of events that would begin in the sixteenth century and culminate in the twenty-first century without further tensions. Rather, the exhibition signaled – although through an excess of works interspersed with documents – formal and thematic approximations. It was organized in eight areas: Maps and Margins; Emancipations;Daily Life; Rites and Rhythms; Routes and Trances: Africas, Jamaica, Bahia; Portraits; Afro-Atlantic Modernisms; and Resistances.

</a> Flávio Cerqueira, Amnesia, 2015. Flávio Cerqueira Collection. Foto: Romulo Fialdini.</figure>

One example of formal-thematic approximation was in the Portraits section, which included: Amnesia, a figurative bronze sculpture by young artist Flávio Cerqueira; two enormous paintings by seventeenth-century Dutch painter Albert Eckhout, representing a woman with a boy and a Black man by himself; the painting Girl from Guinea, by Nigerian artist Uzo Egonu (1931–1996); and an untitledpainting by late Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, donated to MASP in 2018. This curatorial arrangement pointed not only to the renown of some works, for instance Eckhout’s pieces, seen in the country since the huge Brazil 500:Rediscovery Exhibition (2000), including at Mestizo Histories, but also forced into visibility works that are confined to museum collections and rarely moved around due to a lack of projects addressing specific themes – even those of major importance and urgency, such as the debate on race.

<span lang="EN">Africana Diaspora in subway stations and bus stops</span>

Far from MASP or the Tomie Ohtake, certain works were placed around city subway stations and bus stops to get the word out about the exhibition. It would be interesting to know exactly how far these reached, because this was the largest exhibition so far to address the topic of African Diaspora in Brazil, bringing the Americas, Africa, and the Caribbean closer together to reflect upon the effects of the slave trade and the respective marks it left on regional cultures.

</a> Dalton Paula, (left) Zeferina, (right) João de Deus Nascimento, 2018. Both collection of the artist. Photos: Paulo Rezende.</figure>

Among the advertising images disseminated along public transport routes were the portraits João de Deus and Zeferina (2018), by Dalton Paula, a young artist from Goiânia and a big name in contemporary Afro-Brazilian art. Paula brilliantly gives faces to Black leaders of the past whose features are unknown to us. And when his oeuvre penetrates urban space, it encounters other images, such as those showing Black people in conventional advertising. This visual presence is relatively familiar today, yet positive images of Black people in advertising are still unsettling for many people.

<span lang="EN">Another trend?</span>

When the exhibition opened, provocative threads circulated on social media suggesting that exhibitions with Afrocentric themes are a “trend” or “fad.” This pointed to a reaction in certain quarters to institutions of the magnitude of MASP or the Tomie Ohtake seeking to revive their presence in the city and exhibit other artists, including some who were previously silenced in their own collections, giving their works new interpretations and thus new meanings.

What will happen once the “trend” is over? To answer this question, it is useful to point to the dynamic of the arts universe, which promotes some and excludes others over time; it is possible that this trend will pass, like pop art or the big screens of the 1980s did. Some names remain in circulation, while others will only be recognized by large institutions long after their death. With luck some works will become part of institutional collections. How many works exhibited today in Afro-Atlantic Histories were historically relevant when they were produced? How many artists are only being recognized now by a broader public?

<span lang="EN">A low female presence</span>

Blackness as a theme pervaded the entire exhibition, and it would be impossible to list here the exhibited artists interested in the subject – after all, so much was brought together at once. The motivation at two Brazilian museums to coordinate so many borrowed works was impressive.

</a> Janaína Barros, Psychoanalysis of the caress: a prologue about medicines, affect and place. Benedictus fructus ventris tui et fructus terrae tuae fructusque jumentorum tuorum greges armentorum et caulae ovium tuarum. The fruit of your womb shall be blessed, the fruit of your earth, the fruit of your livestock, the breeding of your cows and your sheep, 2018. Artist’s Collection.</figure>

Yet it is important to point out that among the Black artists coming from other countries, the majority were men, as is the case in Brazil. Only a small group of Black Brazilian contemporary women artists were represented: Aline Motta, Janaína Barros, Nádia Taquary, Rosana Paulino, and Sônia Gomes. Except for Taquary and Paulino, each had only one work on display. To a certain extent parallel programming at the Instituto Tomie Ohtake made up for this low presence of women, in a country where many Black artists are active, helping balance the voices of different genders in the exhibition.

The performances of renowned artists in this parallel programming included the works E SE? (AND IF?) Na fresta da certeza, o vermelho escuro(At the Window of Certainty, Dark Red) by Luciane Ramos; On White Paper (black process),by Michelle Mattiuzzi; Como construir baronatos(How to Build Nobility), by Priscila Rezende; and Axexê by A Negra or o descanso das mulheres que mereciam serem amadas (Rest for the Women Who Deserved to Be Loved), by Renata Felinto. The inclusion of Ramos, a <span lang="EN-US">dancer, choreographer, anthropologist, and cultural organizer,</span><span lang="EN">in this visual art field was important, since it required grappling with questions like corporeal discipline and narrative-producing modes in performance.</span>

</a> Sonia Gomes, Memory, 2004. Mendes Wood DM Collection, São Paulo, Brasil. Photo: Eduardo Ortega.</figure>

<span lang="EN">The collection pieces</span>

The exhibition of Black production of the past and present is important, since it is a long overdue way of recognizing artistic creation over time, but it is necessary to go further. This will only effectively be done when Black artists’ oeuvres are no longer identified as “artists collection” and represented as such by their galleries, but rather as part of MASP’s collection.

Temporary exhibitions are relevant, but without collections, other versions of history, as the Afro-Atlantic Histories itself showed, cannot be told. In a country that still traps people in work situations that are analogous to slavery, this would indisputably be the right time to include works by Afro-Brazilian artists in MASP’s permanent collection, promoting their circulation in and outside of Brazil, guaranteeing that more people know them, and finally telling more forgotten or deliberately hidden stories that are waiting to be heard.

<span lang="EN">Alexandre Araujo Bispo</span><span lang="EN"> is an anthropologist, critic, independent curator, and educator.</span><span lang="EN">Afro-Atlantic Histories was on display at the Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP) and at Instituto Tomie Ohtake from June 28 util October 21 2018.

</span><span lang="EN">Translated from Portuguese by Sara Hanaburgh.</span>

</div>

Plus d'articles de

MUNCAB inaugura novo espaço dedicado à arte afro-brasileira

Mãos: 35 anos da Mão Afro-Brasileira

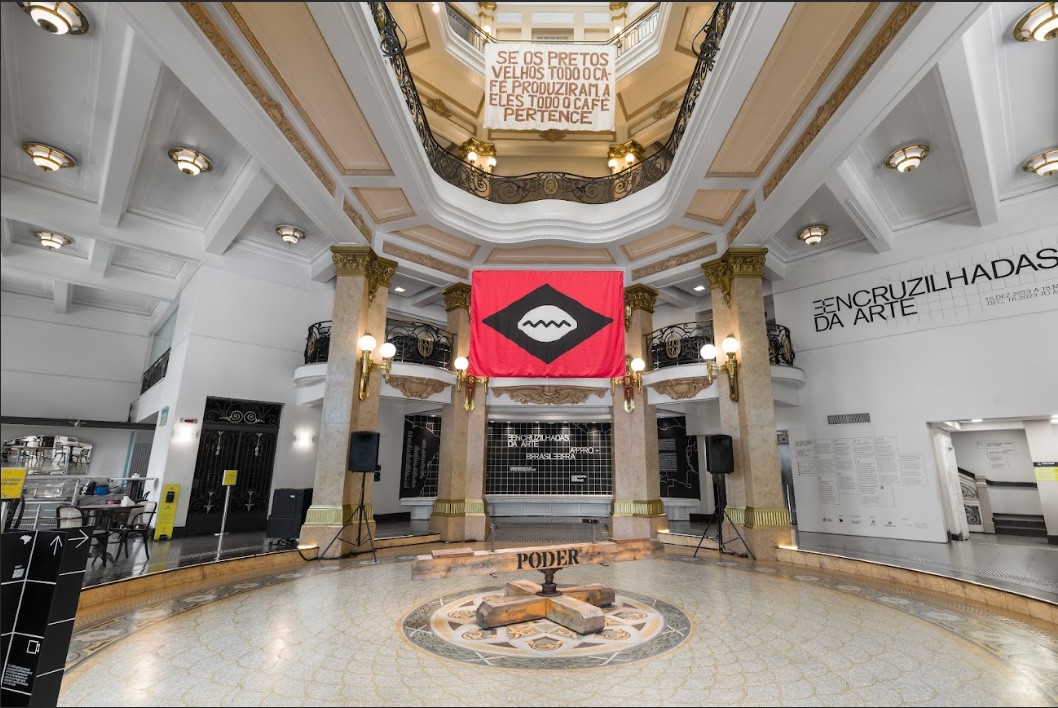

Crossroads of Afro-Brazilian Art

Plus d'articles de

Ancestors and Liberation at Pedrosa’s Foreigners Everywhere

Silver Lion Goes to Karimah Ashadu