Kemang Wa Lehulere: Évaluer les traumatismes personnels et collectifs

25 May 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Will Furtado

5 min de lecture

« Artiste de l’année » 2017 de la Deutsche Bank, Wa Lehulere présente actuellement sa première exposition institutionnelle à la Deutsche Bank KunstHalle à Berlin. Notre auteur Will Furtado s’y est intéressé de près.

L’histoire de l’Afrique du Sud reste encore aujourd’hui difficile à raconter, mais aussi à digérer. Malgré de nombreux aspects réjouissants – tels que la richesse et la variété de la culture, une nature époustouflante et une équipe de football nationale couronnée de succès –, la vie des Sud-Africains est encore marquée par le spectre de son passé sous l’apartheid. Né au Cap, l’artiste Kemang Wa Lehulere a passé une partie de son enfance sous ce régime. Dans son travail, il aborde les effets de l’apartheid sous de multiples angles poétiques.

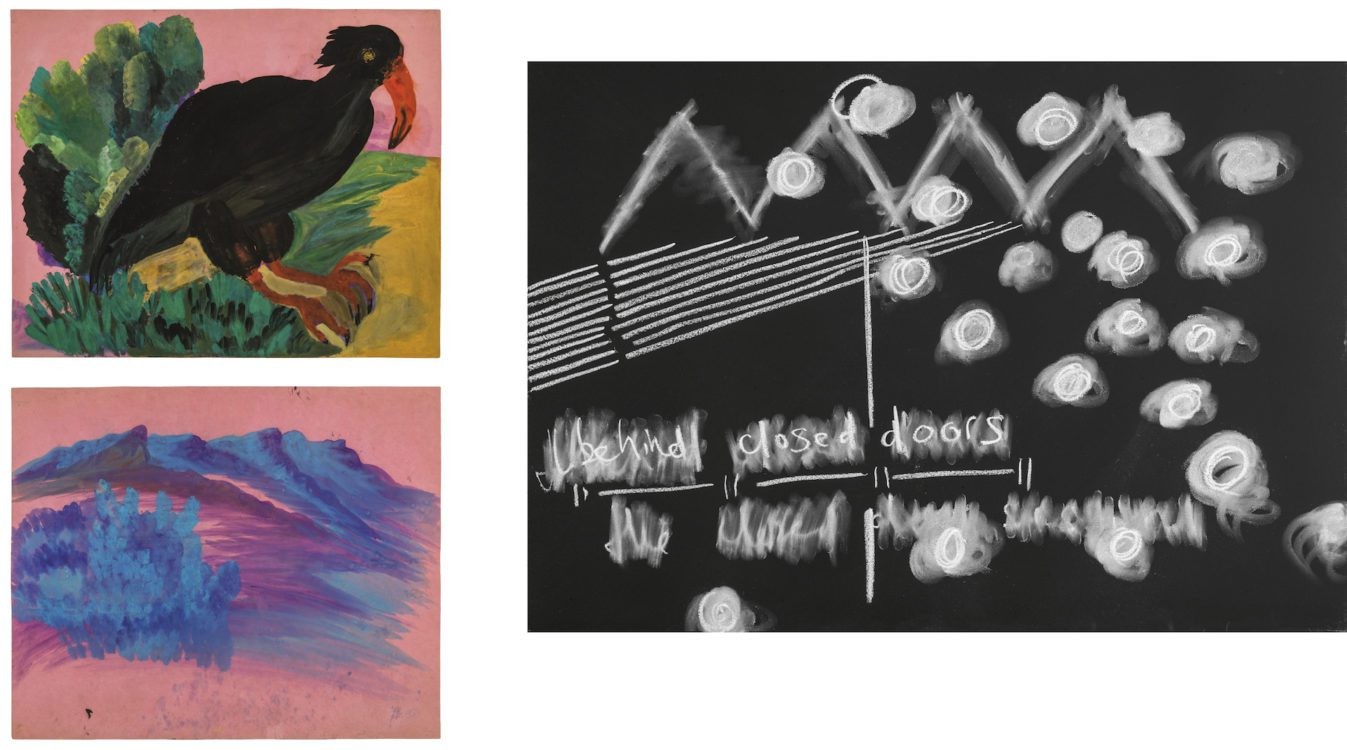

Le point de départ de l’exposition est un hommage à la peintre sud-africaine oubliée, Gladys Mgudlandlu (1917-1979), qui vivait dans le township Gugulethu où Lehulere a grandi. Mgudlandlu a été l’une des premières artistes noires à exposer en Afrique du Sud, et ses peintures de paysages lui ont valu le surnom de « Bird Lady ». « Bird Song » continue de relier le passé et le présent, avec, entre autres, une reconstitution d’une des peintures murales de Mgudlandlu que la tante Sophia de Wa Lehulere avait vue petite fille. D’autres œuvres de Gladys Mgudlandlu, telles des scènes d’animaux ou de rue à la gouache sur papier, sont mises en miroir des dessins à la craie de Sophia Lehulere sur des tableaux d’écoliers qui immortalisent ses souvenirs des œuvres de Mgudlandlu : Does this Mirror Have a Memory (2015). Ce rapport entre reconstitution et reconnaissance donne le ton du reste de cette exposition, qui questionne les nouvelles formes de relations du présent et du passé.

</a> Kemang Wa Lehulere, Does this Mirror Have a Memory 4, 2015. Left: Gladys Mgudlandlu, untitled, 1966. Right: Drawing in collaboration with Sophia Lehulere, 2015. © Kemang Wa Lehulere, Sophia Lehulere, Gladys Mgudlandlu, courtesy STEVENSON Cape Town and Johannesburg</figure>

Many of the works were created especially for this show and most of them explore personal and collective traumas through the universal symbolism of the bird – which can mean the struggle to achieve freedom and displacement. My Apologies to Time (2017) is an installation made up of birdhouses connected to school desks with steel pipes. Here, Wa Lehulere hints at the similarities between birdhouses and schools as places of refuge. Yet, the sculpture also has more solemn connotations. The materials used originate from the schools of a township that was declared a white residential area, which resulted in forced removals. Next to the installation sit ceramic dogs with a humorous expression. On the one hand they symbolize police presence and the rigor of education. But on the other hand they also represent the cherished pets that were not allowed to move with their owners and instead were killed – an act of violence by the apartheid authorities in the 1960s and 1970s.

</a> Kemang Wa Lehulere, Bird Song, Installation view. Front: My Apologies to Time, 2017. Photo: Mathias Schormann</figure>

This dichotomy between good and evil, tender and callous is present throughout and is what gives the show its strength. Projected onto the wall is the video Homeless Song 5 (2017), filmed by the artist in the now empty townships overlooking the ocean. Kemang Wa Lehulere features in it with his naked back serving as a screen for the projection of the title in sign language. American Sign Language also appears elsewhere in the show, apparently symbolizing a universal language, however, this seems somewhat arbitrary, especially since not even the artist is fluent in this language.

</a> Kemang Wa Lehulere: Homeless Song 5, 2017, Videostill, Digitalvideo © Kemang Wa Lehulere</figure>

Overall, Kemang Wa Lehulere does show his flexibility and versatility in mediums and narrative modes when representing repressed stories and adding political commentary to his work. There is one piece on the wall that fully embodies that versatility: the canvas features music notes from an album Wa Lehulere especially recorded for this show with free jazz musician Mandla Mlangeni. Since the note sheet is made out of Afro hair – presumably the artist’s – the work has more than one dimension, paying tribute to Black identity and resistance in a subtle yet powerful and poetic way.

But Broken Wing (2017) is by far the largest and most impressive installation in the exhibition. Made out of parts of old school desks to form objects resembling crutches assembled in a wing formation, the suspended sculpture undulates in the air while one of its detached parts alludes to a broken wing. As many of Wa Lehulere’s other works, this one is imbued with symbolism. Each of the crutches has a set of teeth inserted between the wooden rods, while the teeth are clamped on Bibles in the Xhosa language, suggesting that religion and education can be tools of oppression in disguise.

Despite the earnestness in Kemang Wa Lehulere’s narratives, warmth and wit are very often present. When he addresses loss he emphasizes rebuilding processes, and where there is no apparent connection he unearths missing links. Bird Song shows an artist making use of diverse approaches that put the present into perspective, yet without fetishizing the past.

Kemang Wa Lehulere’s Bird Song, curated by Britta Färber, is on view at Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Berlin, until 18 June, 2017

Plus d'articles de

Samson Mnisi: A Master Posthumously Receives His Due

LGBTQIA+ Diversity Stories

Les sensibilités de Ladji Diaby en matière d'échantillonnage sont matérielles et intemporelles

Plus d'articles de

Beyond the Black Atlantic

Installation View: “May You Live In Interesting Times” at Giardini