Maxine Walke On Her Way Towards Self-actualization

Maxine Walker’s focus has always been on the representation of Black womanhood. London’s Autograph Gallery reintroduces her stunning work on self-realization in an exhibition called Untitled. Our author Sabo Kpade looks on this intimite portrayal of Blackness.

Born in 1962 and active from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, Maxine Walker was a pioneer and stalwart of photography by Black British artists. She co-founded collectives and publications which promoted photographers, and her approach now shows in her small but considerable body of work.

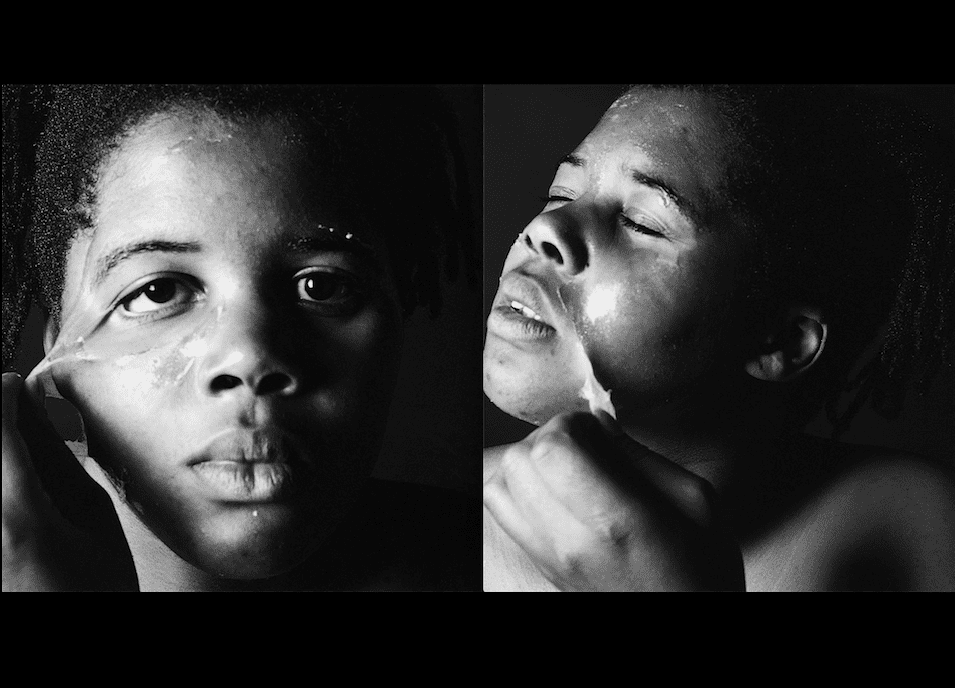

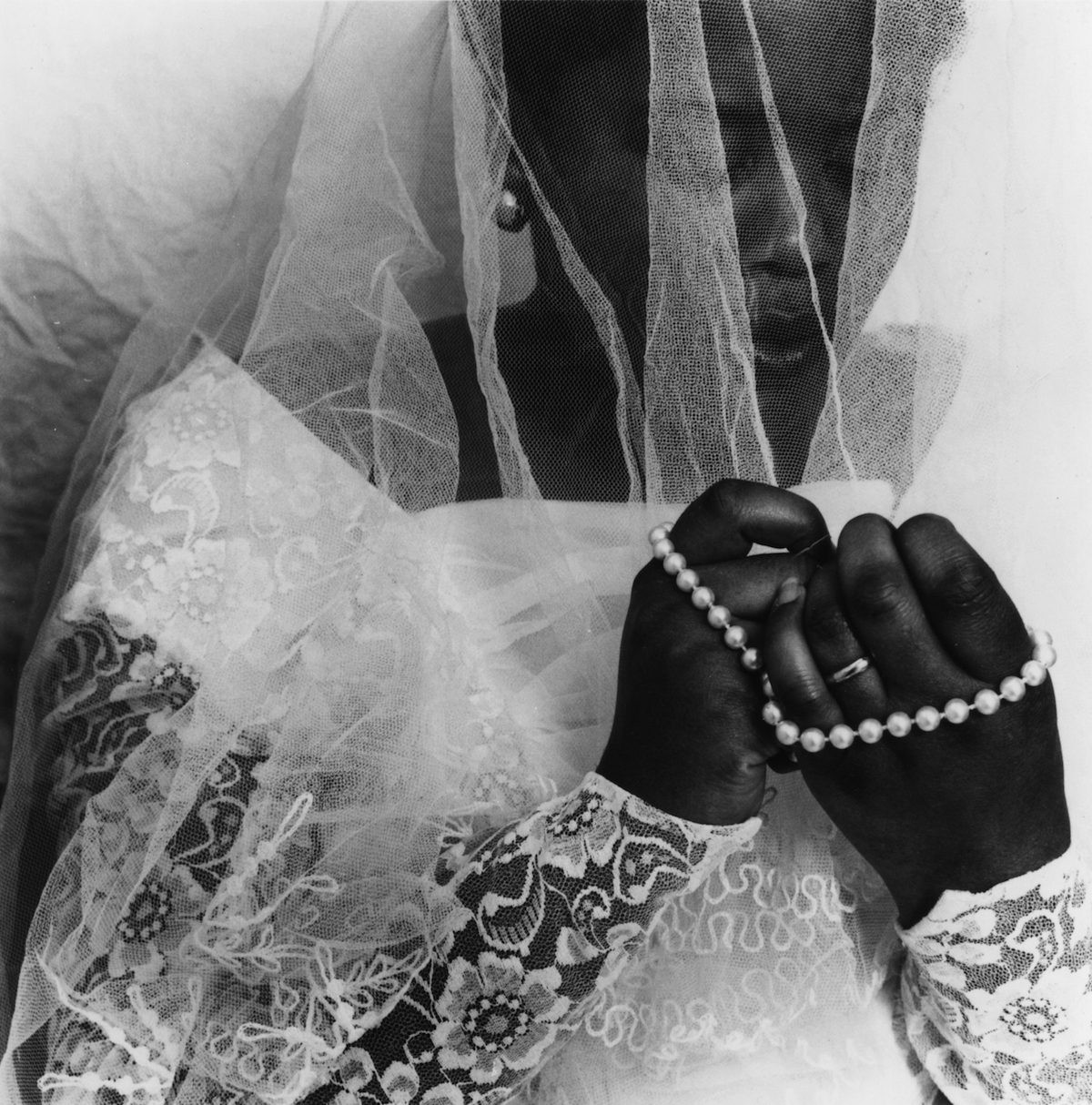

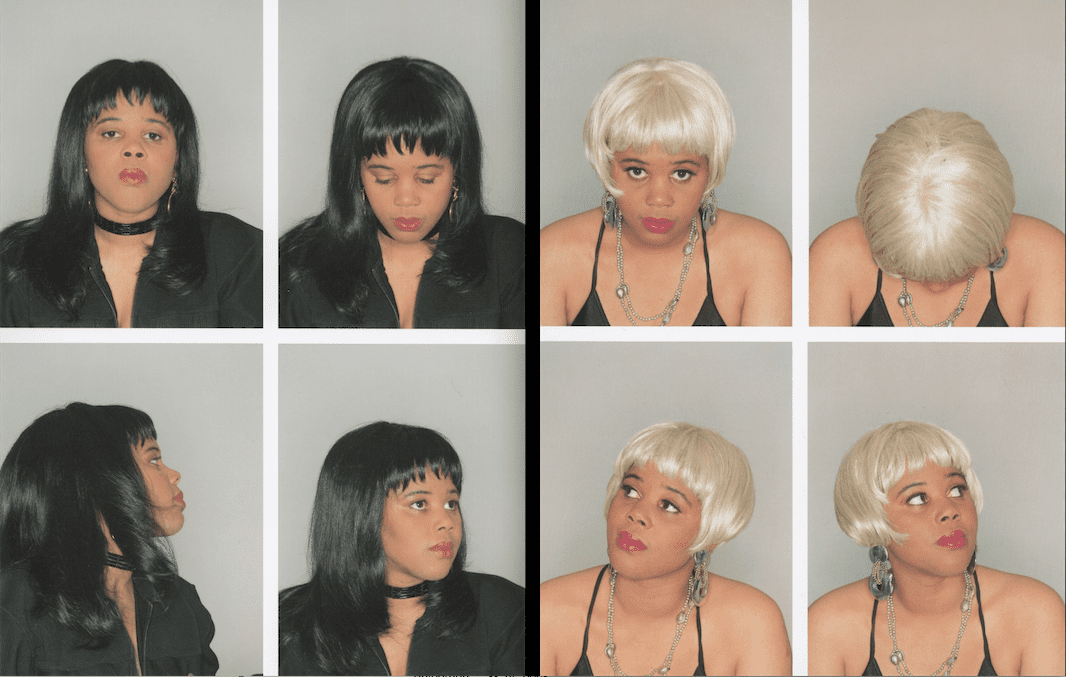

Untitled (1996) makes up the bulk of what is Walker’s first solo exhibition in twenty-three years, at Autograph Gallery. It is a series of close-up self-portraits in which the artist is seen peeling transparent film from her face, a simple gesture repeated in varying poses over ten images. Works from her photo series Black Beauty (1991) and The Bride (1989) are also present, as well as three glass panels that display her art journalism and ephemera, including annotated contact sheets and exhibition literature. (This latter appears to be an effort to simply bulk up what might otherwise seem a scant exhibition.)

Maxine Walker, from the series The Bride, 1989. Courtesy of the artist and Autograph, London. Copyright: © Maxine Walker

In Untitled, eight of the ten images see the artist gazing directly into the camera as she pulls the film away from her face. It is a gaze that is fixed but not fixated. She isn’t luring the camera (or viewer) to herself, neither is she wary of its presence (or the viewer’s) – and this suggests a steely resolve. In the two other images, Walker looks away from the camera in what could be euphoria or relief from the discomfort of peeling a sticky layer of film from her facial skin.

Walker’s intentions of interrogating ideas of selfhood, womanhood, and Blackness are well-stated and celebrated in the exhibition notes in the gallery space and on the website by curators Renée Mussai and Bindi Vora. What isn’t made clear – and this gives one a lot to think about – is whether Walker or the curators see the series as depicting one big act of self-realization, or the logical next stage of self-actualization, or an act that will be repeated at intervals over a lifetime. Is one great awakening of the “self” sufficient, or is continuous renewal (peeling) of false layers more essential for spiritual growth?

(left) Maxine Walker, Untitled, 1995. (right) Maxine Walker, Untitled, 1995. Both images courtesy of the artist and Autograph, London. Copyright: © Maxine Walker

Give these images more time, and even more questions come up: Is Walker suggesting the awakening of the “self” is separate from the awakening of the “Black self”? And are these two states of essentiality equal to one another, or does one come before the other? And if so, why? All this is left to the individual viewer to ponder, though the curators’ laudatory notes – it is a form that should always be scrutinized for bombast – make a sound argument for the revisiting of Walker’s work amid the current swell of interest in the productions of artists of the African Diaspora.

If the ten images were in color, initial visual pleasure would no doubt be increased as the eye is greedy for whatever will excite it, but the black and white is elegant, uncompromising, and nostalgic. Yet the real power of the lot is also derived from the succinct storytelling executed by the artist around a charged subject matter and tastefully curated by Mussai and Vora. The pair’s choice of purple walls color-blocked by white walls makes for a prominent yet unobtrusive background for Walker’s monochrome images – themselves contained by white squares with black frames – creating a neat and compact viewing experience.

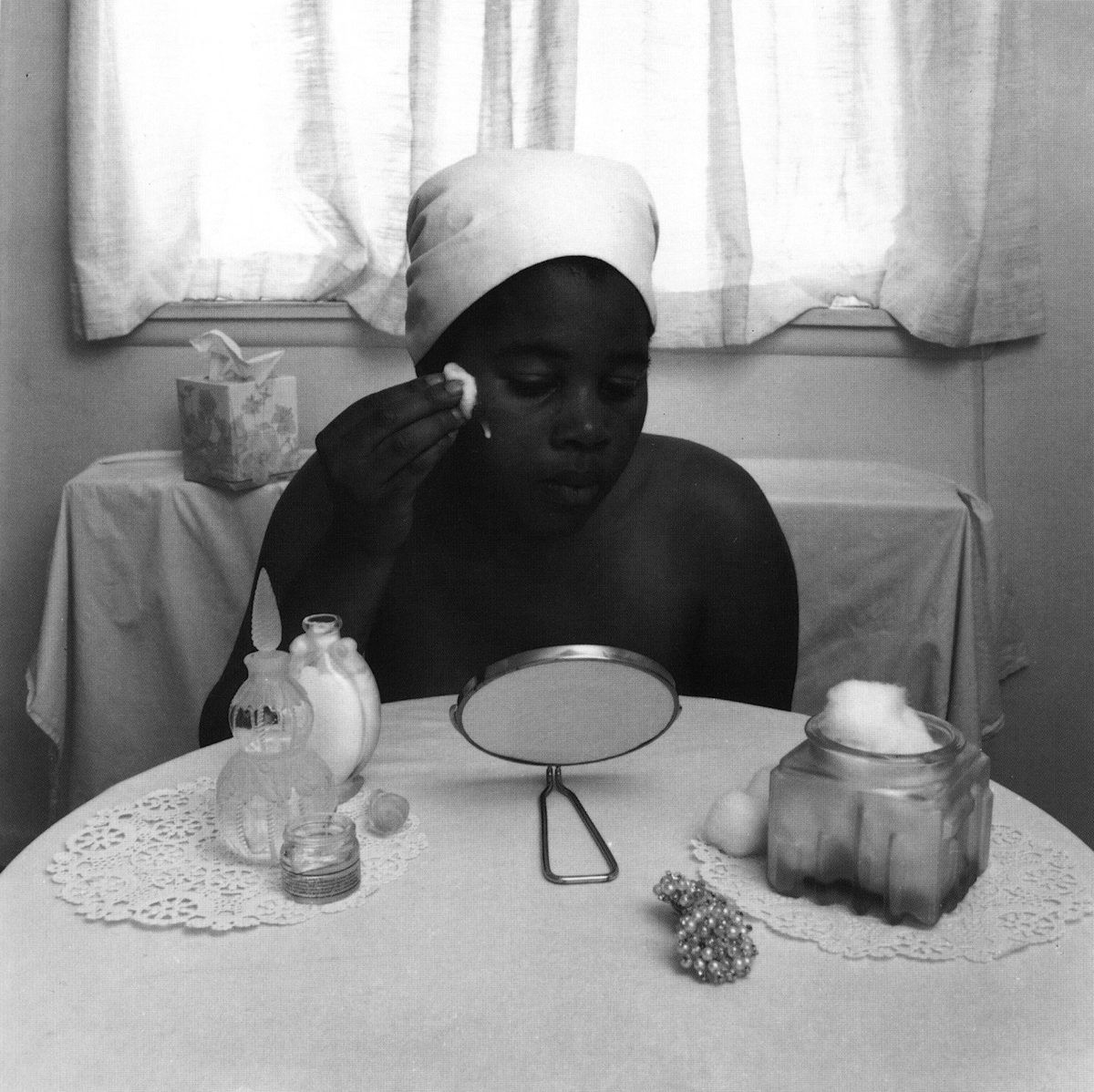

Maxine Walker, Cleansing. From the series Black Beauty, 1991. Courtesy of the artist and Autograph, London. Copyright: © Maxine Walker

These features are shared by the six images from Black Beauty. Walker appears in two, one a close-up of the rich brown skin on her higher back and shoulders, the other showing her before a mirror, either applying or taking off makeup from her face. The other four are shots of candle bars and shapely glassware on pristine white table cloths, elegant studies of spatial configuration that evoke solitude and quiet contemplation. Despite Walker’s serious artistic intentions at the start of the 1990s, in 2019 these images risk looking similar to carefully edited Instagram pages about minimalist home furnishings. Even though its title is loaded, self-explanatory, even insistent, Black Beauty’s gentle images are more persuasive as a meditation on its subject matter than a full-on treatment.

Maxine Walker: UNTITLED is still on view until 17 Aug 2019 atLondon’s Autograph.

Sabo Kpade is a culture writer from London.

Critique

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir : surréalisme, abstraction et figuration panafricains

Critique

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission