In the recently opened Kunsthalle Bega, young Romanian artists demonstrate how to connect certain lines. Our author Mia Harrison visited their group exhibition "lay me down across the lines" to understand how they grapple with personal histories of exoticization, isolation, or objectification. They unpack their ancestral emotional baggage to inspire change by taking an approach that resembles Black feminism in its intersectionality.

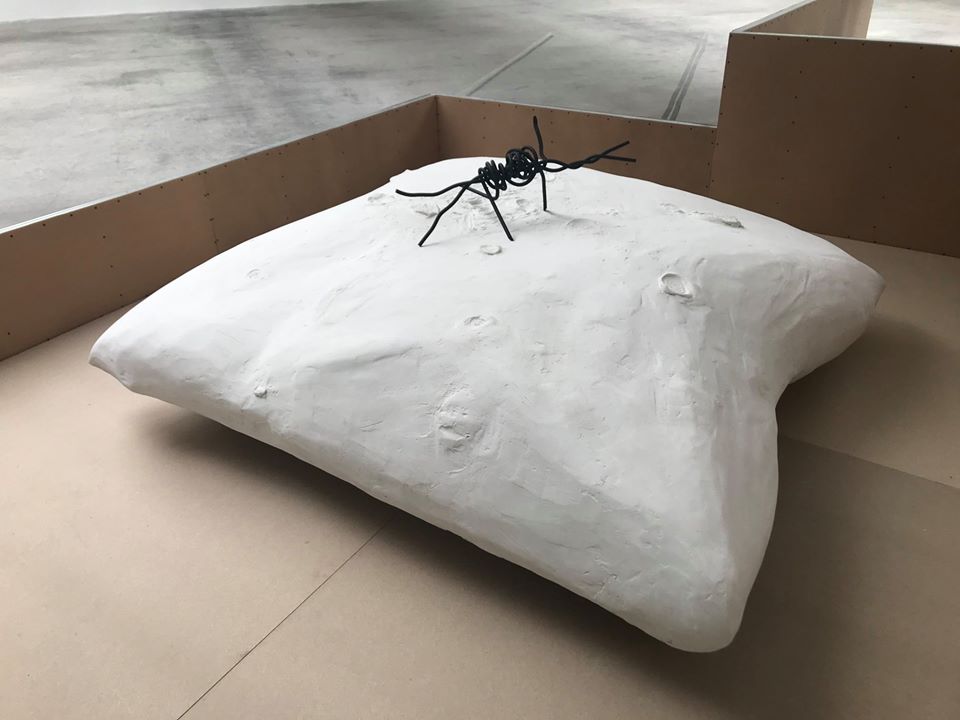

Mihaela Cîmpeanu, SOMNUL - memoria inconștientă a Holocaustului, 2019. SLEEP – The uncounscious memory of the Holocaust, 2019 . Mixed media, plaster, iron and foam, 230 x 220 x 80 cm. Photo credit Kunsthalle Bega

“Your location is on the left.” I looked up from GoogleMaps, confused by the construction site I had arrived at, but then spotted the signage – Kunsthalle Bega. I maneuvered across an unsettled field of dust, rubble, and soil, only sacrificing the apparent whiteness of my canvas shoes – a metaphor perhaps for the thin membrane between the reality I walk through daily as a Black woman and the reality of the exhibition I was about to experience in Timișoara, Romania.

The three-month exhibition lay me down across the lines is the second show at the new location of Kunsthalle Bega, a gallery and cultural hub seeking to present a new generation of artists and social discussions to the public. Brought together by Romanian curator Valentina Iancu, the exhibition’s fifteen artists and fourteen artworks are “placed in a register of personal subjectivity, of personal history or observation abstracted both poetically and politically.” Iancu’s words mirror the approach of many feminists: creating and centering conversations about one’s lived experiences outside the landscape of patriarchy.

Unlike many feminist programs that neglect the ways historical, cultural, and socio-economic factors influence the way a person can live and breathe a feminist life, lay me down across the lines deepens the conversation by taking an intersectional approach. The works and artists dilute the fallacy of a feminist monolith by questioning and pushing back against the ways resistance and liberation can exist, feel, look, and sound for marginalized communities such as LGBTQIA, Roma, and Eastern Europeans. Organized into “curiosity cabinet[s] of thoughts ordered in rooms of their own,” a phrase Iancu borrowed from a queer theory zine called Radical Softness as a Boundless Form of Resistance, the layout of the exhibition was inspired by Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial. Each work stands alone in its room, but the open floorplan allows the audience to activate their agency and choose how to navigate through the narratives, meaning there is space to take pauses between and around the works.

Radical softness – a term coined by New York publisher Be Oakley – is the queer theory that is the foundation the exhibition rests on. Regardless of gender or cultural identity, everyone is in constant contact with a world that tells us how to be, what to think, what to look like, and how you will be treated if you don’t conform to the social norms. How do you walk through the world when you have been cast into its outskirts? Radical softness presents solutions. Although it does not exist in tangible or visible form, and isn’t vocalized or enacted, its power lies in its tenderness. Be Oakley claims: “It is an internal feeling that drives how we carry ourselves in the world.” A resonance of “the beauty of our friendships, support systems, or chosen families.”

Radical softness aligns with the current wave of Black-led passive political acts of protest. It mirrors the rest for resistance movement that the Nap Ministry and Black Power Naps have brought mass attention to. These Black artists and many others outside of their spheres are realizing the importance of restorative actions and acts of self and communal care when an individual or community has undergone immense trauma. “Softness” is the result of a restored state of emotional, mental, and physical rest – a strength that allows oppressed groups to not just survive in existing systems but create alternatives where they can flourish.

Many of the artists in lay me down across the lines are grappling with personal histories steeped in colonization, exoticization, isolation, and objectification. Instead of tackling their oppressions as separate entities, they take a Black feminist approach – an intersectional disrobing of social conventions. Each has found a way to intimately invite the audience into their world, whether or not they are members of the artist’s community. Just like the work being done by African American cultural makers, they unpack their ancestral emotional baggage and air it out to inspire change in everyone.

Hortensia Mi Kafchin, Gramatica divinaţiei / The grammar of divination, 2016. Plaster, 73 x 98 cm; and Bucăţi de gânduri / Pieces of thoughts. Photo credit Kunsthalle Bega

Mihaela Cîmpeanu, a Roma Romanian artist, dives into the pain and trauma we inherit through our DNA. In SOMNUL – memoria Inconștientă a Holocaustului/SLEEP – The unconscious memory of the Holocaust (2019), a large white pillow the size of a child’s bed lies in the center of a room. The usual instinct to leap towards it is quickly rerouted by the fact that it is clearly not full of feathers or memory foam: an entangled metal rod sticks out of the structure. The delicacy of our existence (foam) is punctured by our embodied memories of ancestral narratives.

Romanian activist and artist Sasha Ichim subverts the notion of nudity and the gaze within private and public spaces. Ichim uses the space as an educational platform where the audience can directly learn about the experience of transitioning between genders. On the opening night, Ichim did a live performance that challenged the objectification of trans and marginalized bodies – completely naked, he asked the audience, one person at a time, to also get naked and then ask a question. This action allowed Ichim to de-objectify his own body by finally staring back, an act that falls directly from the tree of bell hooks’ oppositional gaze.

Can magic be a method to transform our trauma? Virginia Lupu, a Romanian artist and photographer who has been documenting a family of Roma witches, believes so. Small formed bits of tin, a large silver spoon, and a water cooler filled with roses are the remnants of Lupu’s opening-night performance, Molibdomancy (2019). Molybdomancy is a form of divination that uses molten metal. Lupu performed a ritual she had learned from her grandmother, who didn’t consider herself a witch but a healer. Lupu’s work speaks to the importance of taking power back from corporations that sell forms of healing and giving that power back to the communities who have used them as a means of survival – indigenous, Black and Brown, and Roma peoples.

Each of these artists affirm their being, their beliefs, practices, and pains, without regret or shame. Each provides ways to move with and through some of the boundaries they were born within. Being in dialogue with one another, these issues, concerns, and celebrations are no longer solitary. They become part of a global movement in which other perspectives are invited to continue drawing the lines.

lay me down across the lines is on view at Kunsthalle Bega, Timișoara, until 13 December 2019.

Mia Imani Harrison is an artist and writer currently based in Berlin.

More Editorial