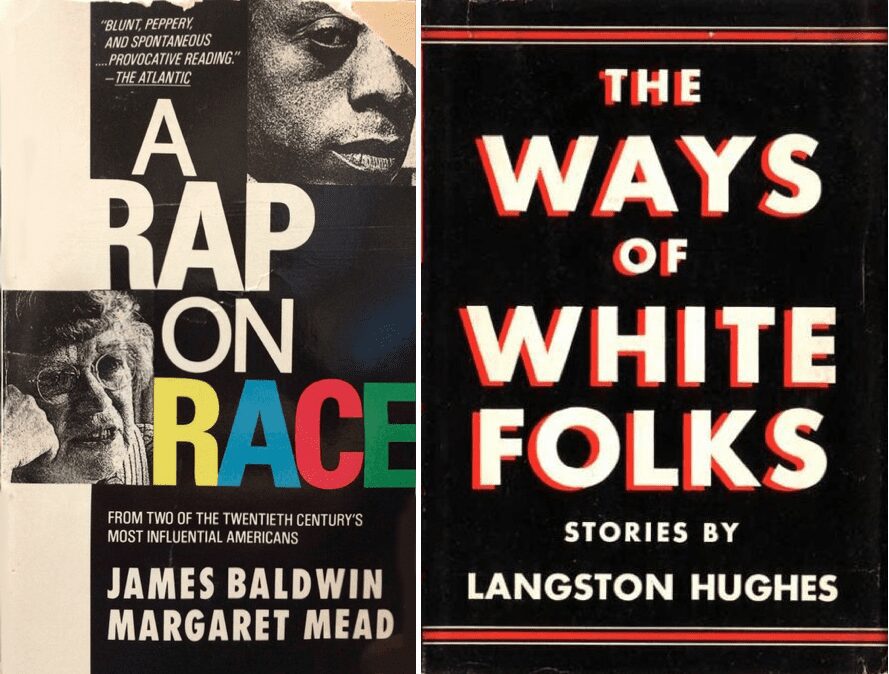

In this series, C& and ArtsEverywhere commission texts inspired by the books in C&’s Center of Unfinished Business last installed at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 2018. Political activist and culture and media theorist Nelly Y. Pinkrah is inspired by Langston Hughes’ The Ways of White Folks and James Baldwin and Margaret Mead’s A Rap on Race. Is it possible to talk about an ordinary German experience as a structurally racialized one in the sense Baldwin and Mead did? Pinkrah thinks so. Here she connects the dots between racisms of the past and present to show how things become invisible when they become structural.

(left) James Baldwin and Margaret Mead, A Rap On Race, book cover of 1970. (right) Langston Hughes, The Ways Of White Folks, book cover of 1934.

While I’m reading the conversations between anthropologist Margaret Mead and political writer and poet James Baldwin, I am drawn to the latter’s rigor and baldness. The transcripts of their seven and a half hours of conversations from 1970 were published in 1971 as A Rap on Race, and race is, among other concepts such as identity, history, responsibility, and guilt, indeed what they are talking about. In one edition’s blurb it is said that Baldwin brought creativity and fire, whereas Mead was the voice of reason and scholarship. Already, this seems to be a racially charged characterization. Nonetheless, Mead’s experience and will to humanism challenges and is challenged by Baldwin’s pessimistic optimism, his analytical, careful, and abiding mind.

At one point the two discuss “the ordinary American experience” – an account that leaves me wondering what exactly that was, and how it would be today. And since I am more suited to talking about my own experience, I ask: is it possible to talk about an ordinary German experience in the same sense? I think it is. Mead, in this section, describes an abusive and criminal scenario in which relations, more often than not, were imagined in the same way: white person as the victim and Black person as the perpetrator. Because the ordinary American experience is coded in a very specific way, with white not merely symbolizing innocence (as with the white sacrificial lamb of Christ), but also purity and power, whereas Black is the bleak opposite (see Richard Dyer’s 1997 book White: Essays on Race and Culture). This is the ordinary American experience repeatedly described in A Rap on Race through different motifs, models, and means.

The implication of any post-colonial nation’s “ordinary experience” is crystal clear: race. The specter of race still haunts everyone, it is affecting and infecting – some suffer or die from it, while others benefit from and exploit it. Eighty-four years ago, in 1934, US-American poet and activist Langston Hughes depicted the differences in experiencing race in a remarkable way in The Ways of White Folks. The book carries fourteen humorous, unbearably tragic, and insightful stories about Black life and Black culture as ingrained in white America of the 1920s and early 1930s. These portrayals of unusual but very real characters are revealing of the conditions of the time and, simultaneously, of human nature. Life then was marked by an inescapable racial segregation enforced via the so-called Jim Crow laws in the southern United States, where lynchings still were usual, and a more subtle racism in the north. So the racisms coming to life in The Ways of White Folks are complex, at times implicit, even playful, or only hinted at.

The materiality of race – that is, experience – can only be undeniable, for it is the simplest of all equations: right-handers are usually unaware of how (often) left-handers are hindered in everyday life because the world was built for the former. Likewise, white people are usually unaware of how often racialized people are hindered in everyday life because the structures that constitute society yield a white perspective. This is where power enters the arena, power which for centuries now has dwelled in whiteness. Or, as Stokely Carmichael once put it: “If a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem.”

Things tend to become invisible when they become structural. Opposite to the widespread belief of the majority, the levels of the individual and the structural are not mutually exclusive, they are dialectic. Racism is part of individual experience precisely because it is so deeply engraved into society’s structures – its schools and universities, prisons, media, its legal systems, its penal systems and so on. Racism, today as well as 100 and also fifty years ago, informs the economic, political, legal and geographical arenas of the world. It is a system of knowledge that structures the social. Racisms are manifold and they transform over time, which is also the reason why radical analyses of the different forms in respective areas are mandatory. Explicit Jim Crow racism, for example, has shifted into today’s condition, which many – in the United States – call the “post-racial.” This buzzword, implying the end of race and racism, helps shift responsibility from the structural to the individual (see David Theo Goldberg’s 2015 book Are We All Post-Racial Yet?). It is a handy tool for those who deny the fact(s) of racism, who turn a blind eye to the daily struggles of so many and to the struggles of many of them to overcome these structures. Whiteness bears the license to do just that when it’s convenient: deny responsibility.

“You know my fury about people is based precisely on the fact that I consider them to be responsible, moral creatures who so often do not act that way. But I am not surprised when they do.”

James Baldwin, A Rap on Race

To return to Mead’s remark from the beginning: If we take a look at who is entitled to be the victim today and who is condemned to be the perpetrator, nothing much has changed. US-American imagery of police brutality against Black people and people of color, images of border detainment and the like, fill the social media newsfeeds of those same people; more so than the mass media news or the minds of those in power to make a change. The same holds true for German public service broadcasting, filled with pictures of Black refugees headed to the West on boats. By crossing the Mediterranean many of these refugees die in the sea which, on several levels, is a grim reminder – if not continuation – of the Middle Passage.

Now, shortly after the end of the unfathomable trial of the terror cell National Socialist Underground (NSU), it is more evident than ever that we do not have the slightest idea of how infused Germany is by Neo-Nazis and their peers. What has recently been going on in Chemnitz – marches by outspoken Nazis, who are proudly doing the Hitler salute and who hunt presumed non-Germans – is a stark exemplification. Beate Zschäpe, the surviving alleged member of the terror group, which killed nine migrants and one police officer, was sentenced to prison for life. Yet the whole proceedings revealed racism’s obscure workings as the police continuously showed their deep institutional racism, from initially labeling the case “the Kebab murders” to turning a blind eye to the NSU while it was still active.

Germany is still in denial of its racism and evidence is everywhere. Recently footballer Mesut Özil quit the national team amid a racist discussion around a picture capturing him with Turkish President Recep Tyyip Erdogan. The police think that they are allowed to racially profile people. In the cultural field, there is the debate on whether the reconstruction of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin simply glorifies Germany’s imperialism. The harboring of colonial artifacts by German museums in general is mostly unquestioned. In the German language there still is no equivalent to the English term race, and the German discourse around it is especially scarce. This includes the circumstance in which people think the German term “Rasse” – more similar to the English “breed” in its meaning – is a perfectly valid way to describe people from different backgrounds. Tellingly, “Rasse” is used in the German constitution, and was part of the justification of the German Empire’s racial extermination campaign in present-day Namibia between 1904 and 1908. This, the first genocide of the twentieth century, was only recognized in 2004 when an apology was issued to the Herero people, but the lawsuit for reparations, launched in 2001, is ongoing. In Berlin’s Wedding district especially, many streets still bear the names of the colonial generals who ordered the atrocities. After years of fighting by activists, three streets in Wedding will be renamed soon but the subway station “Mohrenstraße” (blackamoor street) continues to be a monument of the cities entanglement with colonial history. Language is power, it mediates and manifests the social and here, clearly, power lies with the institutions. Above all, there is evidence in everyday life, manifested in real-time tweets triggered by the #MeTwo movement. Surely we need to teach a lesson to outspoken Nazis through and within the possibilities of the courtroom, as has happened in the NSU trials. But the bigger issue is our whole way of life, a culture that naturalizes the privileges that come with whiteness – and these privileges involve a lot more people than we might initially think.

“The ways of white folks, I mean some white folks, is too much for me.”

Berry, in Langston Hughes’ The Ways of White Folks

Nelly Y. Pinkrah is a political activist and culture and media theorist currently pursuing her PhD on Édouard Glissant and cybernetics in the research training group “Cultures of Critique” at Leuphana University.

C& CENTER OF UNFINISHED BUSINESS

DERNIERS ARTICLES PUBLIÉS

More Editorial