In anticipation of the major exhibition A LABOUR OF LOVE, the writers Ashraf Jamal and Daniel Hewson reflect upon the central topics of the show in two essays.

Mack Magagane, Untitled 21 (from the series … in this city) 2011 - 2012 Archival pigment ink on Innova Fibaprint Matte paper 40 x 60 cm Edition of 5 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist

In anticipation of the major exhibition A LABOUR OF LOVE, the writers Ashraf Jamal and Daniel Hewson reflect upon the central topics of the show in two essays.

I happen to believe, along with the Dalai Lama, that compassion, love, and altruism are not just desirable spiritual attributes, they are qualities that have become fundamental to our survival on this earth. They are the path to a more enlightened society.

Suzi Gablik’s belief in the power of compassion or empathy is rapidly gaining traction, assuming center-stage in political thinking, governance, and cultural practice. For Roman Krznaric, author of Empathy: A Handbook for Revolution, Mandela is its “archdeacon” and Gandhi “the most radical empathist in modern history.” If you believe the hype, it’s boom-time for homo empathicus.

Then again, whether this shift from self-interest and the ‘me generation’ is more than just another rhetorical trend is difficult to gauge. After all, we remain thoroughly caught in the narcissistic maw of ’net culture; witness the rise of the “e-personality” or “e-identity,” and the ubiquity of the “selfie.” For Krznaric, however, there is perceptible global resistance to the “epidemic of narcissism”: “a revolution of human relationships” and an “empathic activism” finding its way back into the art world.

“Art is an instrument,” says Gablik. “It can be used to make a difference [in] the welfare of communities, the welfare of societies…. It is good for something. And this, in large part, should be the true measure of its success – not money, not favorable reviews, or an impressive list of shows, signaling a conditioned allegiance to art world approval.” Gablik is clearly an idealist. While I am more circumspect, though optimistic, I do see the need for the art market to change.

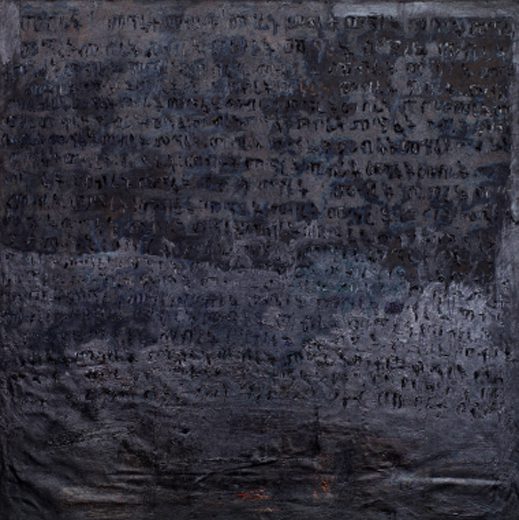

Endale Desalegn, Unknown II, 2014. Oil on canvas, 138 x 133cm. Courtesy of !Kauru African Contemporary Art project

In 33 Artists in 3 acts, the follow-up to her acclaimed Seven Days in the Art World, Sarah Thornton focuses on “diverse points along the following spectrums: entertainer versus academic, materialist versus idealist, narcissist versus altruist, loner versus collaborator.” For Thornton, who engages with artists from “fourteen countries on five continents,” the tension between the opposing camps remains unresolved. It is therefore difficult to isolate a specific orientation as dominant. Rather, what we are witnessing worldwide is an ethical tension.

What is certainly indisputable is the fact that the art world has become polycentric, “a loose network of overlapping subcultures held together by a belief in art.” It is within this more malleable context that we can now measure the growing impact of contemporary African art.

If China dominated the art world in the 1990s, followed by the Indian subcontinent, then today it is art stemming from South America and Africa that is garnering global interest. Cynically this view of African art as “the next big thing” can be perceived as merely pragmatic. However, given over 500 years of Western underdevelopment in Africa, to echo Walter Rodney’s notorious barb, we can also argue that the newfound positive interest in contemporary African art is symptomatic of a global ethical shift and the development of a new humanism.

Empathy, in other words, is not merely a new rhetorical trend but an earnest marker for a changing global sentiment. If African art matters today, it is because it operates as a trope for a new and emergent belief system. In this new system, African art is no longer perceived as a symptom of protest or as an obsessive-compulsive index for a racialized identity politics. Certainly my encounter with the work of Ethiopian painter Endale Desalegn suggests that African art is becoming increasingly more enigmatic, less defined by the dogmatism of a post-colonial resistance culture.

I met Desalegn at the opening of !Kauru 2014, an exhibition of contemporary art from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region. A San word, !Kauru means “to look about, around, or outside of oneself.” It is this immersion in a world beyond the known, and outside of the self, that powered Desalegn as he bounced his thoughts off his thickly encrusted and cryptically lettered black-on-black oil painting titled On/Off. “There is something that exists in the dark surrounding,” he said. “We focus on the visible things, but what about the invisible?”

The desire to engage with a human condition irreducible to the toxic fixations of race and gender is refreshing: a signal for a complexity of mind and spirit which, as Frantz Fanon famously pointed out in Black Skins, White Masks, was perceptually denied the black African who had come to occupy a “zone of non-being.”

Endale Desalegn, There is something that exists in the dark surrounding, 2014. Oil on canvas, 127x 120cm. Courtesy of !Kauru African Contemporary Art project

Historically judged a mere object, a corporeal thing bereft of feeling and subtlety, the African body, today, is being radically reconfigured by the continent’s artists. Here Endale Desalegn is a case in point. “I don’t know about the future,” he remarked. “I have no clear definition of identity. To stand we need some ground.” For Desalegn it is the groundlessness that matters, the limbo, despite claims to the contrary, that distinguishes a healthily unsettling moment in contemporary African art practice.

South African photographer Mack Magagane reaffirms this limbo. His show, tellingly titled Somewhere between here, conveys the feeling of indeterminacy and suspension which epitomizes the mood of the times. Capturing what Juan Orrantia calls “simple, intimate, anonymous moments,” Magagane’s photographs ask us to ponder “the meanings of the night, of loneliness, of individuality amidst density.” This minor key in which he registers the city of Johannesburg is what gives Magagane’s photographs their compelling and enigmatic allure. ”I have constantly asked myself whether Johannesburg is like any other city or a unique city of its own. What really makes Johannesburg? Is it the dark emptiness when night hits? Or the sudden energy when the sun begins to rise?”

Standing in the darkened space of ROOM, a gallery in Johannesburg, with light emanating from Magagane’s electrified photographic boxes, I immediately sensed the power of the invisible made visible – and a new moment in South African art. Magagane’s word for this estranging distillation is “uncanny,” and, when one stands in the midst of his images, it is precisely this sense that one is visiting an unconscious scene, or a plainly obvious but unnoticed scene, that sparks the imagination.

The absence of declaration and the rejection of “rhetorical noise” mark the change in contemporary African art. Magagane’s photographs convey the artist’s sense of “being part of something yet at the same time being remotely attached.” This may suggest alienation or even voyeurism and yet, countering this existential view, I’d suggest that the artist is all about empathy: a sense of being a part of a greater world that connects us. If African art matters today – and here Magagane and Desalegn are seen as symptomatic of this global interest – it is because it embodies a global empathic revolution.

Martin Buber, a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps, best captures this revolution when, in his landmark study I and Thou, he states:

« I imagine to myself what another man is at this very moment wishing, feeling, perceiving, thinking, and not as a detached content but in his very reality, that is, as a living process in this man … The inmost growth of the self is not accomplished, as people like to suppose today, in man’s relation to himself, but in the relation between one and the other, between men. »

Henry David Thoreau understood this communion well. “Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other’s eyes for an instant?” he asks. And, in this regard, Santu Mofokeng’s famous portrait of his brother – Eyes Wide Shut – captures this intimacy perhaps the most potently. It is here, in this moment between, that we not only see our fallibility but our power to become the other of ourselves. It is a moment that captures what we euphemistically call love.

Santu Mofokeng, Eyes Whide Shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens from the series ‘Chasing Shadows,’ 2004. Silver print. Courtesy of Gallery Momo

As Marina Abromovic would have it, “Artists should be the oxygen of a society. The function of the artist in a disturbed society is to give awareness of the universe, to ask the right questions, to open consciousness and elevate the mind.” My focus on empathy here is akin to “oxygen,” or, in the words of performance artist Andrea Fraser, an understanding of art-making as “a profession of social fantasy … [in which] overvaluing and overestimating possibilities [and] investing in futures that do not really exist are occupational requirements.” It is in this spirit that I’ve broached the possibility of a new moment, a new ethical turn with global traction, increasingly evident in local and continental art practice.

A LABOUR OF LOVE, December 3, 2015 – July 24, 2016, Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt-on Main

Ashraf Jamal is an educator, editor, and cultural analyst based in Cape Peninsula University of Technology in Cape Town. He is the co-author of Art South Africa: The Future Present, co-editor of Indian Ocean Studies: Social, Cultural & Political Perspectives, and the author of Predicaments of culture in South Africa.

More Editorial