“Germanomania” and the Myth of Nationalism

The unfading legacies of Western racism is a paradigm C& continuously examines through the visual art lens. Art from African perspectives still doesn’t hold an equal footing on the global stage, despite favourable statistics and figures. This adds to a collective false sense of equality, and reinforces the trap of consensus in the art world. In this C& series we’ve compiled a selection of articles from our archive that best dissect the innocuousness of racialized society. This time Natasha A. Kelly looks at how Marimba Ani’s book Yurugu still proves relevant in understanding the continuity and centrality of racist thoughts and racial myths in Germany and Europe.

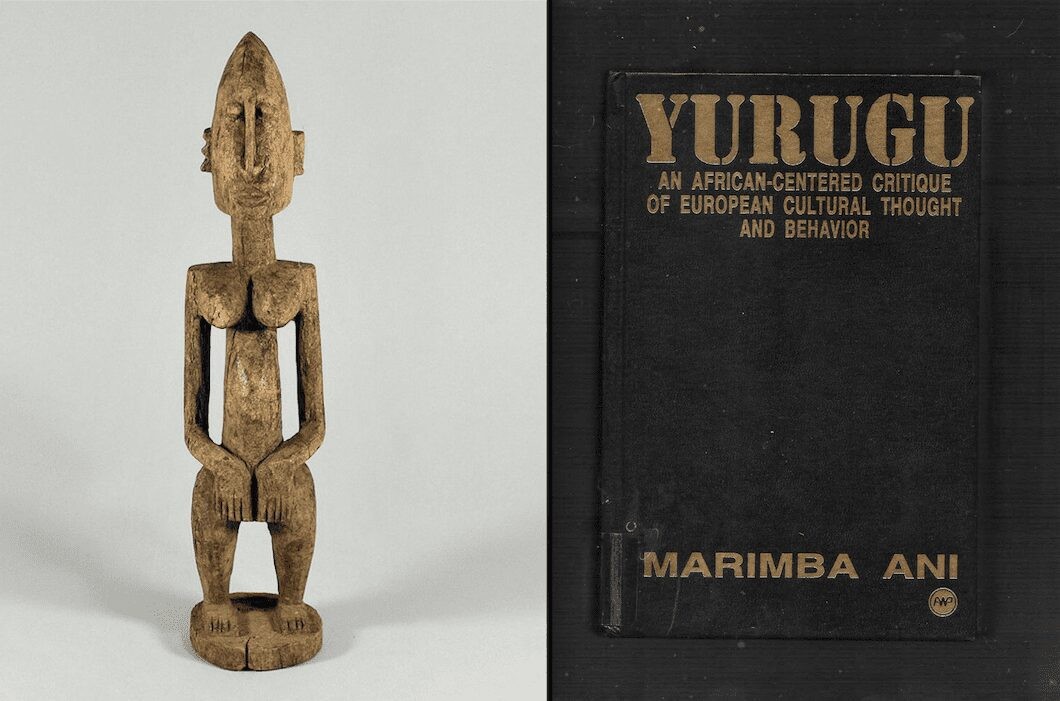

In this series, C& and ArtsEverywhere commission essays and articles inspired by one of the books in C&’s Center of Unfinished Business now installed at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. In this essay, inspired by Marimba Ani’s book Yurugu, author Natasha A. Kelly looks at how the title still proves relevant in understanding the continuity and centrality of racist thoughts and racial myths in Germany and Europe.

Amma, the supreme God of the Dogon people of West Africa, created all beings according to the universal principle of complementarity. S/he therefore equipped each individual with twin souls – both female and male – at birth. In one case, however, a male existence named Yurugu did not want to wait for the completion of his full formation process. Instead, he arrogantly competed with Amma, which resulted in his spirit being incomplete. Therefore Earth emerged imperfectly and some of the planet’s inhabitants were single-souled beings. Today, Yurugu’s descendants remain destructive and rejected by Amma, who had given his female soul away.

Published in 1994, African American anthropologist Marimba Ani’s book Yurugu uses the figure of Yurugu to describe Europe’s self-claimed superiority and destruction. Her comprehensive critique of European thought and behavior examines the causes of global white supremacy, proposing a three-fold conceptualization of culture, based on the concepts of asili (origin), utamawazo, (worldview), and utamaroho (energy) – three terms Ani borrows and/or transforms from Swahili. The book also addresses the term maafa, based on a Swahili word meaning “great disaster” to describe the enslavement of African people.

“Utamaroho and utamawazo are extremely forceful phenomena in the European experience. They are brought together in the asili, the root principle of the culture. Neither the character of the European utamaroho nor the nature of its utamawazo are alterable unless the asili itself changes.” (p. 17)

Ani characterizes the origin of European culture (asili) as dominated by the concepts of separation and control, with separation establishing dichotomies like “the European” and “the other”, “thought” and “emotion”, and control being disguised in universalism. Her model describes the European worldview (utamawazo) as structured by ideology and biology. Its vital force (utamaroho) is domination, which is reflected in the imposition of European culture and civilization on peoples around the world. Europe’s success, however, is dependent on the construction of national consciousness because of the pre-eminence of the political nature of Europe’s utamaroho. The question of national identity is therefore essential to inspire the people to achieve what they perceive to be greatness.

According to Ani, European cultural history reveals the centrality of myth and myth-making to political successes. She describes the myth of national origin among Europeans as “Germanomania”[1], as Germanic people were perceived (and perceived themselves) to be of “unmixed origin” (p. 259) and therefore superior with a universal civilizing mission in relation to all other nation states. In Spain, England, and other European countries, the desire to be associated with a German was compelling. The English, for example, prided themselves in their alleged German heritage until World War I. Anglo-Saxonism held that the English people descended from German Angles, Saxons and Jutes.

The myth of the Ayran soon became a conviction that helped Germans to seek power over others. What surfaces as central in the European experience in this regard is the myth of the national/racial origin. For example, Martin Luther, who was celebrated for his inspiration of religious reformation, was above all a German nationalist rebelling against the control of Latin Christians. He compared the Pope to the Antichrist and gave voice to national feelings of the German people who felt exploited by Rome. Centuries later, Adolf Hitler would follow in the same tradition. The earlier claims by biblical characters were then replaced by racial and nationalistic ideologies. After the end of World War II, much of Europe was in ruins. Only few national states could consider the liberation from National Socialism their victory. Europeanization eventually (re-)gained strength, which in a cultural context referred to the loss of national identities through the emergence and alignment with a unifying European identity – with the myth of Aryan descent always reigning supreme.

Presently, the German far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) wants to rebuild the European Union into a loose union of nation states, as they believe that Germany is losing its sovereignty. In their politicalprogram for the federal election in 2017 they clearly claimed that Germany would leave the EU in the same way Great Britain had, if the current union did not return to a “Europe of Fatherlands”. At the same time the party called for Germany to cancel the transfer-union and leave the Euro zone, as the basic monetary rules (no liability for the debts of other countries and no public debt over 60 % of the respective GDP) had not been followed. Since – in their opinion – migration from Africa to Europe is expected to destabilize the European continent in a few years, the party seeks to, “leave our descendants a country that is still recognizable as Germany”. This statement makes AfD’s national/racial ideology evident, which did not prevent the party from being (re-)elected into the German parliament, coming in third with 13% of the national vote.

Moreover, the various manifestations of the European self-image reveal an utamaroho that is consistent with that of white nationalism. In this sense, Ani’s publication still proves relevant in understanding the continuity and centrality of racist thoughts and racial myths in Germany and Europe, offering an analytical tool to remove the mask of white supremacy. Thus, the concept of asili allows for the unveiling Eurocentric worldviews and dominance by observing the various expressions and characteristics of European identity through an African-centered lens. And this, according to Ani, is the only perspective from which Europe can be observed as culturally and ideologically incomplete.

Natasha A. Kelly is a British-German editor, author, and lecturer holding a PhD in Communication Studies and Sociology, her research focusing on colonialism and feminism. Her dissertation, titled, “Afrokultur. ‘der raum zwischen gestern und morgen’” (Unrast Verlag 2016), deals with the life and works of W. E. B. Du Bois, Audre Lorde and May Ayim, three Black knowledge workers who framed Afro-German identity.

[1] Cited by Marimba Ani, p. 256, with reference to Leon Poliakov, The Aryan Myth: A History of Racist and Nationalist Ideas in Europe, trans. Edmund Howard, New American Library, New York, 1974, p. 82.

C& Center of Unfinished Business was on show until 15 January 2018 at ifa-Galerie, Berlin, Germany. From 26 January until 30 March 2018 it can be viewed at Akademie der Künste, Pariser Platz, Berlin.

Essai

The Museum of Black Futures

Sons caribéens : les possibilités connectives de la radio

Cultures Imprimées Noires Canadiennes : de Legs Discrets et Persistants

Essai

The Museum of Black Futures

Sons caribéens : les possibilités connectives de la radio