Our author Gauthier Lesturgie in conversation with Virginie Bobin , curator of “The Day After” , Maryam Jafri’s first exhibition in France.

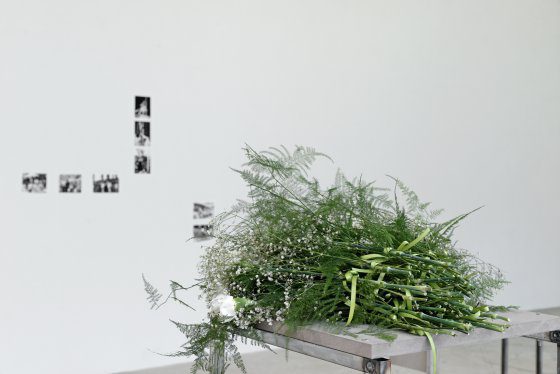

Maryam Jafri, ‚The Day After‘, view of Kapwani Kiwanga, ‚Flowers for Africa, Federation of Mali’, 20112, at Bétonsalon Cenzre for art and research, Paris, 2015 © Aurélie Molle.

Maryam Jafri’s first exhibition in France, “The Day After,” created a frame within which numerous practitioners were invited to participate during the period of the project, which ran for four months from 18.03.-11.07.2015. Maryam Jafri’s work-in- progress, Independence Day : 1934-1975, was the starting point of the exhibition. Begun in 2009, I.D : 1934-1975 is a collection of photographs picturing events, which occurred on the day of independence of former colonized countries. Jafri, who is based between Copenhagen and New York, collected these documents in 29 different archives she found in Asia and Africa. The exhibition at Bétonsalon in Paris presented a selection of 57 of these archive photographs. “The Day After” will be shown in an extended version in 2016 at Tabakalera, center for the creation of contemporary culture in San Sebastián and Blackwood Gallery in Toronto.

Virginie Bobin, associate curator at Bétonsalon and co-curator of the exhibition with Mélanie Bouteloup, discussed with Gauthier Lesturgie the collaborative format of the project, its realization, first assessments and future development.

“At the same time a process of despoilment and dispossession is at work: above all, the archived document is one that has to a large extent ceased to belong to its author, in order to become the property of society at large […].” (1)

Gauthier Lesturgie : “The Day After” is collective in its purpose and realization, but it is also a collaboration between different organizations involved in the project. Can you explain the role of each of the actors who made this project, and how the collaborations worked? Did you follow a specific plan?

Virginie Bobin : Every project developed at Bétonsalon – Centre for Art and Research forms around collaborations and partnerships that allow the sharing of knowledge and resources, from a micro-local to an international level. Our aim is to create interactions between artistic and academic research, by creating the conditions for encounters between people who work in different fields and contexts. We believe that “research” can take many different forms, and that shifting the boundaries between disciplinary categories or networks can only encourage the production and sharing of knowledge. Bétonsalon is at the interface between the university we inhabit and the “art world” in which we operate. We can act as a mediator between the two, and with multiple collaborations around a project we can multiply the chance encounters and the circulation of ideas.

For “The Day After,” several groups of collaborators/partners were established. Short- and long-term research collaborations with Paris 7 University, for instance, as well as the UDPN network – a 3-year, collaborative research project that brings together several departments of universities across Paris to investigate the “uses of heritage” in relation to digitization, a question Bétonsalon has been concerned with for a while. (See the project from 2013, Something More Than a Succession of Notes). For us, these collaborations are an important way of sustaining long-term research in dialogue with academics and students, while giving a greater visibility to the artist’s work and facilitating conversations and crossover points.

Our role is also to ensure that the projects live on after an exhibition at Bétonsalon. For “The Day After,” we established a co-production partnership with Tabakalera (San Sebastian, Spain), which will tour the exhibition in April 2016. The team at San Sebastian will work closely with Maryam Jafri in the months prior to the exhibition, as we did here, to develop specific research aspects and new contributions. The exhibition will also tour to Blackwood Gallery (Toronto, Canada) in 2016, and Maryam is working on an artist’s book that will be partly shaped by all the above-mentioned conversations.

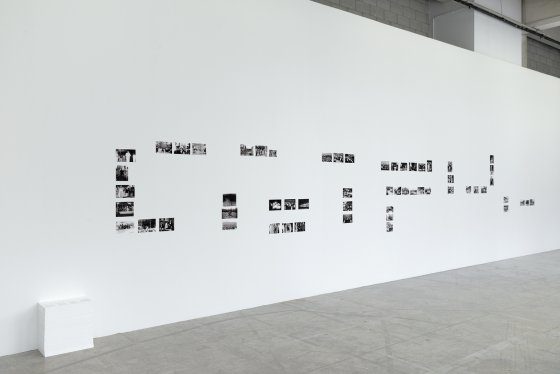

Maryam Jafri, ‚The Day After‘, detail of Maryam Jafri, ‚Idenpendence Day 1934 – 75‘, 2009, ongoing at Bétonsalon Cenzre for art and research, Paris, 2015 (c) Aurélie Molle.

GL : This collaborative format you set up and investigated is necessary to deal with documents that refer to collective historical events. Multiplicity of voices is essential in this context, and even more, oral discourses (which are often missing in exhibitions). This avoids rigidity and a privileged voice – whether that of the artist, the curator, or the institution. How is this “hierarchy” tackled during the collaboration?

VB : Any project is necessarily collective and as a curator I try to emphasize this aspect by facilitating situations where multiple actors can engage at different stages and “co-produce” the project. We could say that “The Day After” built itself around different “circles” or collectives: the first circle was formed by Maryam Jafri, Mélanie Bouteloup (director of Bétonsalon and co-curator of the exhibition), and myself. Between June 2014, when we started talking about the project, and the exhibition opening in March 2015, we had numerous conversations that slowly gave shape to the project. Instead of clinging to a fixed idea of our positions as “curator” or “artist,” we tried to navigate smoothly between the different roles. The three of us selected all the materials eventually presented in the show. A second circle formed with the addition of Hadrien Gérenton, the young artist who worked with us to design and build the sculptures/structures that accommodate the different materials in the exhibition. In some cases we did not know whether elements would be included the exhibition until a few days in advance, so we played with ideas, and Hadrien would either respond positively or propose alternative structures we had to adapt to. A third circle pre-existed the project: it consisted of all the researchers, historians, archivists, journalists, or artists who helped Maryam to access the images that constitute Independence Day 1934-1975. It was obvious that their work should be made visible in the exhibition, and we also invited many of them – who had not met before – to contribute to the public program. This circle expanded to a broader network that formed around the project during the research in Paris, who also contributed to, or attended, the events. The different groups of students, the different audiences also formed new circles. All these intersected and interacted before, during, and after the project. This process of collective-building was partly cultivated, or “curated” (with the crucial aim of involving voices rarely heard in Paris, France, or Europe), and partly evolved organically in the course of the project.

GL : The collected photographs of Independence Day : 1934-1975 are displayed in a large mosaic on one of the main exhibition walls. Originating from several archives in former colonized countries in Africa and Asia, they are shown out of geographical context, as part of an archive of archives. This extensive selection makes Independence Day very open to external interventions and comments. Was it decided from the beginning that Independence Day would constitute the starting point of the project?

VB : Independence Day 1934-1975 is a densely layered work, which triggers multiple questions about the way history is framed by its representations, about the role of photography in the dissemination of its narratives, and about the way the processes of independence were and are perceived in different contexts, national or non-national. The status of these images today is also important… So yes, from the very start we wanted to inscribe the work in a broader perspective and assemble materials in a constellation that would highlight multiple, albeit subjective and fragmentary, possible readings. As I have said, we already had an amazing source of materials in the work of all the researchers who helped Maryam since 2009. It was also very important that neither I.D. 1934-1975 nor the materials surrounding it would be dormant, hence the vivid program of workshops, talks and events to activate them, to generate frictions, to open alternative or even contradictory vantage points. This explains the very open title, “The Day After.”

Maryam Jafri, ‚The Day After‘, detail of Maryam Jafri, ‚Idenpendence Day 1934 – 75‘, 2009, ongoing at Bétonsalon Cenzre for art and research, Paris, 2015 (c) Aurélie Molle.

GL: “The Day After” uses and reflects on several types of documentation, notably by questioning the status of the archive in relation to historical events. The project itself is producing events and documents. Some documents are progressively displayed in the show (such as the report of a workshop at Paris Diderot university). Will this constitute an archive in itself? If so, how will it be accessible and reflected?

VB : That is a very important question. Maryam really considers Independence Day 1934-1975 as a work-in-progress, building towards an artist’s book in which she wants to present all the photographs she has gathered throughout the years (more than 500). In that sense, “The Day After” is also a “rehearsal” or a testing ground for the book, which will also include some theoretical texts. As I said, the exhibition at Bétonsalon was only a part of the project, with extensions at the university library for instance, which displayed a selection of books related to the questions raised in the exhibition; or with the online reader Qalqalah, that will continue to exist after the show is closed, sharing texts by Maryam and some of the contributors to the exhibition. Most of the public talks were recorded and will be broadcast on Radio 22 Tout Monde, an online radio operated by Khiasma (Les Lilas), a long-time interview partner of Bétonsalon. This will give them a longer, “autonomous” life. And last but not least, there are all the longer-term after-effects of the project, such as collaborations initiated during some of the public events that will sustain the memory of the project. More “days after”…

(1) Achille Mbembe. “The Power of the Archive and its Limits,” in Refiguring the Archive. Springer Publishing, New York, 2002.

More Editorial