“Chagas photographs reveal the metamorphic nature of objects and spaces in Luanda”

24 Septembre 2013

Magazine C&

14 min de lecture

Katia Anguelova and Claudia D’Alonzo of lettera27 Foundation, talk to Stefano Rabolli Pansera, curator of the Angola Pavillion, winner of the Golden Lion for Best National Participation, and director “Beyond Entropy”. Katia Anguelova / Claudia D’Alonzo: Can you tell us briefly about how the project for the Angola pavilion started? What are the connections with …

Katia Anguelova and Claudia D’Alonzo oflettera27 Foundation, talk to Stefano Rabolli Pansera, curator of the Angola Pavillion, winner of the Golden Lion for Best National Participation, and director “Beyond Entropy”.

Katia Anguelova / Claudia D’Alonzo: Can you tell us briefly about how the project for the Angola pavilion started? What are the connections withBeyond Entropy and the project that was presented previously at the architecture biennale?

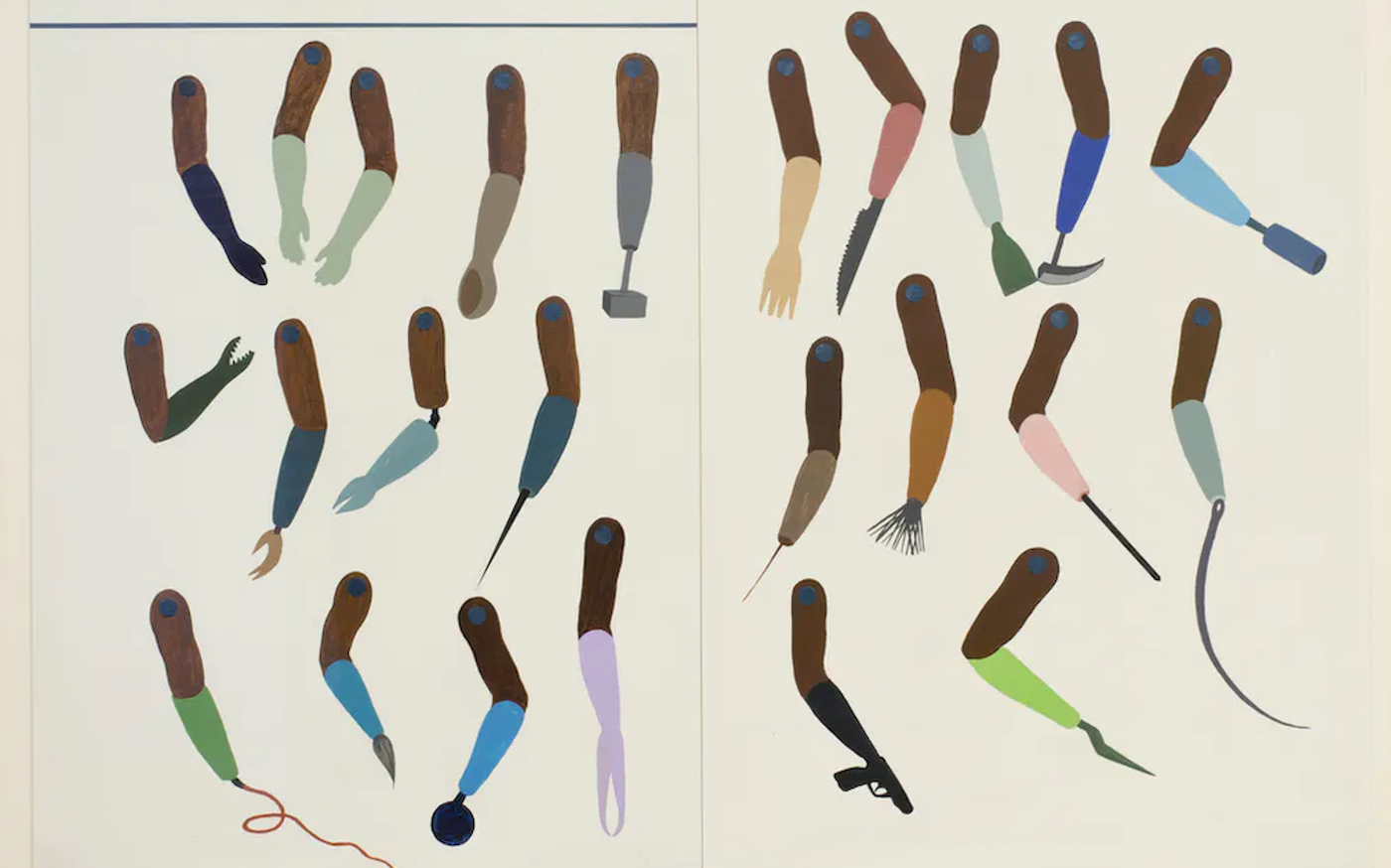

Stefano Rabolli Pansera: The Angola Pavilion at the Art Biennale stemmed from the research that Beyond Entropy had carried out during the Architecture Biennale in 2012. The two pavilions (for the Architecture and Art Biennales) are the expression of the same research into the nature of the African city. Beyond Entropy is an organisation that focuses on the relationship between Space and Energy, beyond the rhetoric of sustainability. In fact, the concept of Energy cannot be reduced to a purely technical matter but is instead a concept for understanding space and its transformation. Through its collaboration with artists, architects and scientists, Beyond Entropy develops specific territorial models in Europe, the Mediterranean area and Africa. In these places Beyond Entropy analyses a specific condition from the “energy” perspective and develops a series of projects that serve as prototypes. Although the same methodology is adopted, the results are different because conditions differ from region to region. In 2011 Paula Nascimento and I decided to analyse Luanda as a paradigm of the urban and territorial transformations taking place (albeit on differing scales and intensities) in many other cities in sub-Saharan Africa. Luanda’s extraordinary contradictions cannot be explained with conventional architectural models: it is an extremely populous city – seven million inhabitants – with hardly any infrastructure, a horizontal urban development and a massive population density (in areas like Cazenga buildings are never more than one storey high but the population density exceeds that of Manhattan). How can a model be created to understand this city? How can the concept of Energy be used to suggest new living possibilities for this urban space? The incredible aspect of African cities is that every space performs a number of functions: a home is at the same time a residence, office, storage area, garage, etc. This ‘metamorphic space” is that which Beyond Entropy has identified as the authentic component of the spatiality of an African city and which was recreated by both the Angola Pavilion at the 2012 Biennale (with a natural park which simultaneously operates as infrastructure for the production of biomass and as a biological sewage system), and the 2013 Pavilion (with an urban catalogue of Luanda’s spaces through the photographs of Edson Chagas).

KA / CDA: How did the collaboration with the artist Edson Chagas start and why did you choose to develop the project for the Pavilion with him?

SRP: We always aim to respond to the general theme of the Biennale. During the Architecture Biennale of 2012 we created a Common Ground for energy and even this year we adhered to the theme defined by Massimiliano Gioni. The “palazzo enciclopedico” (encyclopaedic building) contains a contradiction: as soon as a building moves towards universality, it ceases to be a building and instead becomes a city. Only a city contains a multiplicity of conditions and spatial possibilities in the unit of form (even though urban form is conflicting and complex). For us, the theme of the encyclopaedia is strictly linked to the urban dimension and can be connected to the research on the space of the African city that began last year. The first curatorial choice was to avoid the temptation of creating a general show of the state of art in Angola. We chose to have a single artist exploring the theme of the Palazzo Enciclopedico as an urban catalogue. In this case the choice of working with Edson Chagas came about quite naturally. Paula already knew about Edson’s work, which consists in an urban catalogue of objects and spaces. From the work Found not Taken we only selected the photos that were taken in Luanda to reinforce the consistency of the theme and the identity of the Pavilion. The design of the Pavilion was then finalised with the help of the Pavilion’s art directors, Tankboys, who had a decisive role in defining the format of the exhibition and the catalogue.

KA / CDA: The centrality of objects in our lives and imaginations is a recurring theme in literature -just think of of Les Choses (Georges Perec), Las Cosas (Jorge Louis Borges) and so on… Objects that are examined by critics and semiologists for their symbolic and metaphoric value, and their role as material artefacts and depositaries of ideas on history, also become bearers of stories. What is the role of the objects portrayed in Chagas’s photographs? What type of story/stories do they tell?

SRP: The centrality of objects is always present in every encyclopaedic desire. The attempt to create a universal knowledge starts with trying to collect and order the things we see around us. Edson’s work consists in finding abandoned and destroyed objects, repositioning them within the urban fabric and then photographing them to form a sort of urban encyclopaedia. As the title itself implies, Found, not Taken, the act of taking objects and repositioning them in the urban context is indicative of the fact that every encyclopaedia involves a process of documentation as much as a poetic reconstruction of reality. Aside from the psychological interpretation or the anecdotal reconstruction of the stories behind the Luanda photographs, it is important to interpret Edson’s work within the conceptual framework defined by Beyond Entropy. If the authentic feature of the African city is indeed the metamorphic use of space, Edson’s pictures reveal how apparently irrelevant objects can be transformed within the city and, at the same time, transform the perception of that very city and inform people about a new way of living within it.

KA / CDA: The series of photographs of Luanda is part of the Found Not Taken cycle that Chagas worked on in another two cities, London and Newport, using the same visual registration process for abandoned objects. What do you see as the similarities and differences in terms of the stories these objects tell us about the three cities?

SRP: Many of the pavilion’s visitors thought that Edson Chagas’s photographs were taken in Venice. In fact, the objects are arranged in generic spaces that refute the vernacular rhetoric we often adopt in our imaginary vision of African cities. Luanda is a contemporary metropolis in which spaces tend to look just like those of other metropolises.

What we are interested in is not so much the content of the photographs or the similarities between Luanda, Newport and London, but the method chosen by Edson, and the process of taking abandoned objects and recontextualising them in the city. This technique can be applied to every urban space and is the result of a way of conceiving objects and spaces as iridescent components of a single entity. This specific manner of looking at a city and the objects within it reveals a specific sensitivity which manifests itself clearly in African cities and which can be projected in other urban contexts.

KA / CDA: What do the objects photographed by Chagas tell us about the ongoing transformations in the city of Luanda and its complexity?

SRP: Edson’s photographs reveal the metamorphic nature of objects and spaces in Luanda. Edson’s gaze does not indulge on the vernacular aspects of Luanda and does not show the objects as fetishes or static entities that are photographed for their aesthetic qualities. The objects are represented in an exchange of mutual relations with the city. Abandoned and irrelevant object acquire a new value in the urban context and invent new means of imagining the city and city and living within it – we could scarcely hope for a more consistent portrayal of the African city.

KA / CDA: You chose to make the installation an exhibition of his work and at the same time a catalogue, which the public can compose by selecting the images to bring with them. It is a gift to each user and an invitation to make a selection and construct a personal reading of the series of photographs, which can be an overall impression or instead be the result of focusing specifically on a single image. What type of mechanism do you want to activate and what connection is created between examining the project as a whole and focusing on the individual posters, where we return to the idea of the object being collected, decontextualized and brought elsewhere?

SRP: The exhibition is the catalogue and the catalogue is the exhibition. The Pavilion itself is housed within a very beautiful and complex space: Palazzo Cini is a Museum of Renaissance art, with wonderful paintings by Pontormo, Giotto, Botticelli and Piero della Francesca. It is inaccessible for much of the year and none of the existing set-up could be altered or removed from the walls. This is why we decided to fill the central space of the rooms with posters that could be statuesque features in the space. Every ream of the posters corresponds to one of Edson’s photographs. The public moves around the space and works its way through an urban and typographical archipelago. Nothing has changed on the walls, but the posters dictate the urban topography the public moves around in. By collecting the posters, visitors create their own personal encyclopaedia of Luanda. The Pavilion can also be interpreted as a mise-en-scene of the same conceptual mechanism as Found not Taken: a series of objects that have been found (Edson’s posters) are positioned in a new setting (Palazzo Cini) and create unexpected connections which reactivate the space and make it usable and alive once again.

KA / CDA: Since you have been working in Luanda for some time and have developed a detailed knowledge of the context, could you give us your opinion of its artistic and cultural scene on the basis of your own personal experiences? Which cultural initiatives or spaces do you see as being representative or particularly interesting?

SRP: In Luanda there is an extraordinary cultural buzz: there are the Luanda Triennale, non-profit organisations and institutions with internal prestige like the Sindika Dokolo Foundation. Beyond EntropyAfrica operates in an independent manner in the Angolan scene: although it is always in contact with these institutions, in many regards, it is an outsider to Angola’s cultural scene. The Biennale pavilion, which was promoted and curated by Beyond Entropy, organised the first bilateral meeting between Angola’s Ministry of Culture, represented by Dr Rosa Cruz e Silva, and the Italian Ministry of Culture, represented by Dr Massimo Bray, to promote constant cooperation between the two countries. The true heritage of Angola’s Pavilion will be measured by the effects which can be produced on Angola’s culture sphere and in terms of artistic exchange between the two countries. In this regard, starting from March 2014, a group of Angolan artists will be guests of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Calasetta (Sardinia) for a first attempt at a geopolitical collaboration between Italy and Angola which revolves around cultural exchange and artistic production.

</p>

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube’s privacy policy.Learn more

Always unblock YouTube

</p>

</p>

</p>

PGlmcmFtZSB3aWR0aD0iNTAwIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjI4MSIgc3JjPSJodHRwczovL3d3dy55b3V0dWJlLW5vY29va2llLmNvbS9lbWJlZC9kQUllb3V2dHFHST9mZWF0dXJlPW9lbWJlZCIgZnJhbWVib3JkZXI9IjAiIGFsbG93PSJhY2NlbGVyb21ldGVyOyBhdXRvcGxheTsgZW5jcnlwdGVkLW1lZGlhOyBneXJvc2NvcGU7IHBpY3R1cmUtaW4tcGljdHVyZSIgYWxsb3dmdWxsc2NyZWVuPjwvaWZyYW1lPg==

KA / CDA: We know that in Luanda there is also a major buzz linked to the defence of its architectural heritage. There are many associations that deal with the preservation of the tangible and intangible heritage, that is seen as historical memory and identity. Is this an issue you have touched upon during your research in Luanda? What link do you think there can be between this type of focus and the city’s future transformations, changes to its urban structure and the ways of living within it?

SRP: The defence of the architectural heritage is a very important issue in Luanda as it is connected to the post-colonial dimension and the establishment of a national identity for Angola. Local artists and architects are systematically involved in this. Recently Kiluanji Kia Henda developed an interesting project on the appropriation of the colonial and post-colonial monumental iconography in an attempt to create a new narrative identity for Angola. This is something which interests us but which we did not strictly consider in the formulation of the programme for the pavilion. In terms of the relationship between the existing architectural heritage and the urban transformation of Luanda, we believe that the metamorphic nature of space in Africa can reveal innovative and unexpected ways for the re-utilisation and transformation of these spaces.

As in Kiluanji’s photographs, every reappropriation becomes a desecration of existing iconographies. Perhaps in Angola the appropriation of the architectural heritage can become a resource and an incentive not to conserve (as has often happened in Europe), but instead promote innovation and the unexpected.

Edson Chagas

After his degree in Photojournalism at the London College of Communication, he attended the documentary photography course at the University of Newport. Since 2007 he has lived and worked in Luanda, the capital of Angola and developed his own personal research as a photoreporter beyond the standard practise of this field. His debut as the 55th International Exhibition of Art – the Venice Biennale is the crowning achievement of his internationally renowned work, thanks to his participation in exhibitions all across the globe. His work was presented at the Luanda Triennale in 2010 and he took part in the SP-Arte e SOSO collective in Sao Paulo (Brazil) in 2011, as well as the GIZ- Deutsche Gesellshaft fur Internatonale Zusammenarbeit workshop in Ethiopia, which led to a series of itinerant exhibitions, from the National Art Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa to the Rheinishes Landesmuseum in Bonn (Germany). In 2012 he took part in the MABAXA Project in Luanda and the festival RAVY Rencontre d’Arts Visuels in Yaoundé (Cameroon). Finally, in 2013 he was part of the NO FLY ZONE collective at the Berardo Museum at the CCB of Lisbon, and the “Landscape” exhibition in Brescia’s Palazzo Gallery.

Paula Nascimento, Director Beyond Entropy Africa

She lives and works in Angola, in Luanda. She is a graduate of Southbank University and a member of the Architectural Association of London. She worked for Alvaro Siza Architects and RDA and is a consultant for COBA Consultores de Energia e Ambiente. Since 2011 she has been directing the activities of Beyond EntropyAfrica. With Stefano Rabolli Pansera she curated the Angola Pavilion at the 13th International Architecture Exhibition – the Venice Biennale.

Stefano Rabolli Pansera, Director Beyond Entropy

After working with Herzog and de Meuron between 2005 and 2007, he was Unit Master at the Architectural Association between 2007 and 2011. He has held conferences at the universities of Cagliari, Cambridge, Naples, Wuhan, Seoul and Madrid. In 2010 he set up Beyond Entropy which operates in Europe, the Mediterranean area and Africa. Since 2012 he is the director of the Foundation MACC Museo di Arte Contemporanea di Calasetta and the Galleria Mangiabarche in Sardinia. Alongside Paula Nascimento he curated the Angola Pavilion at the 13th International Architecture Exhibition – the Venice Biennale.

Beyond Entropy Ltd

Is an agency for regional, urban and architecture production that uses the concept of energy as its main research instrument for designing and creating spaces. Beyond Entropy is an analytical method for understanding the spaces we live in (cities, rooms or landscapes). It is an operational strategy which unveils new paradigms for the conception, creation and management of alternative forms of the urban and architectural narrative.Beyond Entropy operates on a global scale in critical spatial situations: from uncontrolled urban expansion to the collapsing infrastructure of desert islands, like Calasetta in Sardinia, to the recovery of the over-populated cities in emerging countries, like Angola, and protected areas in the historic centres of towns.Moreover, it develops projects in which theoretical research and the architectural product merge into a bespoke proposal that goes beyond the rhetoric of sustainability.

The interview has been realized by Katia Anguelova and Claudia D’Alonzo forlettera27 and originally published onDoppiozero. lettera27 is a non-profit foundation based in Milan. Its mission is to support the right to literacy, education, and the access to knowledge andinformation with a focus on Africa.’

de

Fonction

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room : annotations sur l’art, le design et les savoirs diasporiques

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

de

Urban life

Shades of Green

Porter notre attention aux artistes plutôt qu’aux zones géographiques