At New York’s New Museum, the last exhibition conceived by Okwui Enwezor functions as a thorough overview of contemporary art by Black artists in the US, writes Alexandra M. Thomas.

Rashid Johnson, Antoine’s Organ, 2016. Black steel, grow lights, plants, wood, shea butter, books, monitors, rugs, piano, 189 x 338 x 126 3/4 in (480 x 858.5 x 322 cm). © Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America gathers a transgenerational group of thirty-seven contemporary artists, all of whom are concerned with Blackness – as a site of trauma, possibility, hope, horror, grief, or grievance. Numerous histories and affective experiences abound in the curatorial vision and delayed realization of the show. Curator Okwui Enwezor originally conceived of Grief and Grievance and worked diligently on it in 2018, before his premature death in March 2019. Enwezor’s political imperative was for the exhibition to open at around the same time as the 2020 presidential election. Both Enwezor’s death and the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the exhibition timeline back further than originally planned, making Enwezor’s introductory wall text – repeated on each floor of the exhibition – read as a historical artifact of a recent yet different era in US politics.

Glenn Ligon, A Small Band, 2015. “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni

The text interrogates a moment from the 2016 US presidential election, in which Donald Trump announced that he would host a rally at the Gettysburg memorial grounds in Pennsylvania – the site of the turning point battle in the American Civil War and the monumental speech by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863. Enwezor traces the political inheritance of that moment and its resurgence in Trump’s presidential campaign: grieving the losses of those who died defending Black freedom and the disgruntled Confederates who after losing the war would stew in their white grievance for centuries. Reflecting on the Black Lives Matter movement and its ongoing protests directed at state-sanctioned violence against Black people, Enwezor poignantly notes, “The crystallization of black grief in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance represents the fulcrum of this exhibition.” The resulting exhibition mines that history and exposes the horrors of white supremacy, the resilience of Black Americans, and the artistic strategies taken up in our contemporary moment to address the condition of Black life, which poet Claudia Rankine describes as being in a perpetual state of mourning.

(Front) Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s, THE FULL SEVERITY OF COMPASSION, 2019. (Back) Garrett Bradley, Alone, 2017 (still). Single-channel 35mm film transferred to video, sound, black-and-white; 13 min. “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni

The exhibition begins on the ground floor with Garrett Bradley’s 2017 black-and-white short film Alone, accompanied by haunting prints from Terry Adkins’ Ars series (2012) and Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s hefty sculptural installation THE FULL SEVERITY OF COMPASSION (2019). McClodden’s appropriation of a cattle squeeze recalls how animal behaviorist and autistic advocate Temple Grandin was inspired by the apparatus to invent a device for autistic people – often called a “hug machine” – as well as recalling restraints used in queer and kink communities. This emphasis on haptic intimacy contrasts with the Bradley film, which narrates the harrowing story of Aloné Watts and her loneliness due to her partner’s incarceration, as she mourns the loss of touch and of being held. Adkins’ prints are in part about being held captive, as they appear somewhat akin to x-ray views of a slave ship – the foundational example of forced separation and captivity in tight quarters. These entangled symbols and their legacies – the slave ship, the prison industrial complex, and the overlapping formations of disability, kink, and the built environment – yield endless inquiries on captivity, technology, subjectivity, desire, and space.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (policeman), 2015. Acrylic on PVC panel with plexiglass frame, 60 x 60 in (152.4 x 152.4 cm). Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Mimi Haas in honor of Marie-Josée Kravis. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

The galleries on the next two floors immerse the viewer in an almost maze-like installation of works by contemporary Black artists. This explosion of formal strategies from so many artists makes the exhibition seem at times like a “highlights in recent Black American contemporary art.” Photographs by Deana Lawson and Dawoud Bey, viewed in dialogue, provide an opportunity to admire images that are very disparate aesthetically but are united under the same rubric of capturing and representing the contours of everyday Black life. The different styles of painting on display raise questions about the limits and possibilities of abstraction and social realism, a debate present in modern and contemporary art by Black people for at least a century. Dark, atmospheric paintings by Julie Mehretu and Mark Bradford present artistic approaches that are fundamentally different to, for example, Kerry James Marshall’s paintings. Marshall’s Untitled (Policeman) (2015) is a portrait of a Black police officer sitting on the hood of his car, rendered in varied shades of blue. There is often a presumed separation between representational politics and representational paintings, and the convergence in Untitled (Policeman) is intriguing. What can it mean that Black police officers exist – even a Black president – yet anti-Black racism and police violence persists? Perhaps this tension is at the root of aesthetic debates in the Black radical tradition. I am reminded of the murder of Emmett Till in 1955, and his mother’s decision to have an open-casket funeral and to print photographs of his mutilated body in Jet magazine, or the current circulation of police brutality videos to raise awareness. The promise of representation has always been to expose horror and mobilize for remedy, yet issues of voyeurism persist.

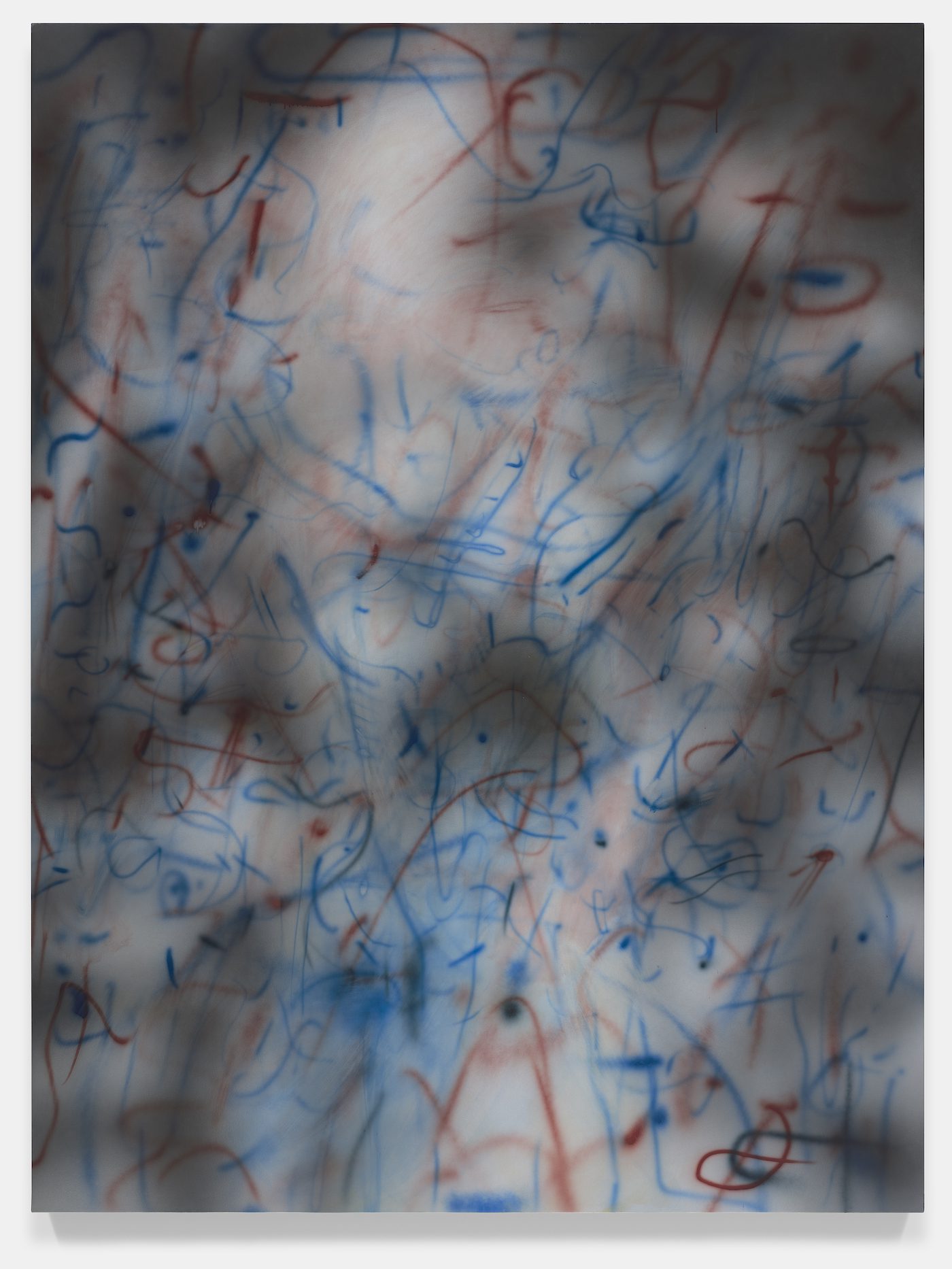

Julie Mehretu, Rubber Gloves (O.C.), 2018. Ink and Acrylic on Canvas, 96 x 72 in (243.8 x 182.9 cm). Private Collection. © Julie Mehretu. Courtesy of the artist, White Cube, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

As Trump has left the White House and we are returning to the liberal status quo under the Joe Biden presidency, I would venture to revive these discussions through the example of Breonna Taylor, who was murdered by police in Louisville, Kentucky in 2020. While our entry points change based on our moment, the cosmic and revolutionary potential of art by Black artists remain consistent. Much like critiques of neoliberal circuits of representation, there is also room to critique the circulation and commodification of Taylor’s image – there are no perfect starting points. The sociopolitical manifestations of racism morph into varied shapes, but critiquing this world and reimagining another remain fundamental concerns in the cultural production of Black people.

Arthur Jafa, Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video, sound color; 7:25 min. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

This might be best exemplified by two works made in the same year that are on display at the start and end of the exhibition: Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, The Message is Death (2016) and Rashid Johnson’s Antoine’s Organ (2016). Jafa’s short film is a montage of the terror, devastation, innovation, and jubilation that coalesces in Black life, with the hip hop gospel hit Ultralight Beam by Kanye West and Chance the Rapper playing in the background. Footage of Serena Williams’ victory dance, Civil Rights protests, police violence caught on tape, NASA footage, and homemade twerking videos are among the hundreds of scenes amalgamated in the film. It is a montage of the affective, political, pleasurable, and creative textures of Blackness – motifs woven throughout the exhibition as a whole.

Deanna Lawson, Jouvert, Flatbush, Brooklyn, 2013. Pigment print, 40 x 49 ¾ in (101.6 x 126.4 cm). © Deana Lawson. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Exiting the elevator on the top floor of the exhibition, the viewer is greeted with explosions of color in an enormous installation by Rashid Johnson. A massive grid-like structure of black scaffolding takes up almost the entire spacious gallery, overflowing with plant life, books, musician Antoine Baldwin’s piano, shea-butter busts, and other miscellaneous items. It is simultaneously chaotic and serene – inviting, pleasurable, and curious-looking. Still, much like Jafa’s film and the entire exhibition, it is not fully consumable or describable. This is why visual and expressive culture is a core element of the Black radical tradition: our revolutionary imaginations are irrepresentable by language alone. The boundless scope unleashed by the tensions and insights from Black visual culture is also what makes Black grief and white grievance a thematic lens that feels severely limited. It might be that the delayed realization of the exhibition made the focus feel less urgent, or that it is disingenuous to force a uniting rubric onto an exhibition that functions as a thorough overview of contemporary art by Black artists in the US.

Dawoud Bey, Fred Stewart II and Tyler Collins, from the series “The Birmingham Project,” 2012. Archival pigment prints mounted on Dibond, 40 x 64 in (101.6 x 162.6 cm). © Dawoud Bey. Courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA and Rennie Collection, Vancouver

The sorrowful irony of the matter is that the conceptual frame of grief parallels the mourning of Enwezor himself. As the exhibition passed from his hands to a team of his collaborators – Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash – it is clear that great lengths were taken to honor Enwezor’s thinking at the time, in order to adequately honor his prodigious legacy and his final curatorial gift to us. And it remains a gorgeous survey of the artists who animate today’s debates on contemporary art.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America at New Museum New York is on view through 6 June.

Alexandra M. Thomas is a writer and PhD student at Yale. Her interests include: modern and contemporary art of global Africa; transnational feminisms; queer theory; and critical museum studies.

More Editorial