Aria Dean Conjures a Deathly Spectacle

21 April 2023

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Lola Ayisha Ogbara

6 min de lecture

In Chicago, the artist helps us experience connections between animal slaughter, violence towards Black peoples, and the brutalization of captured bodies.

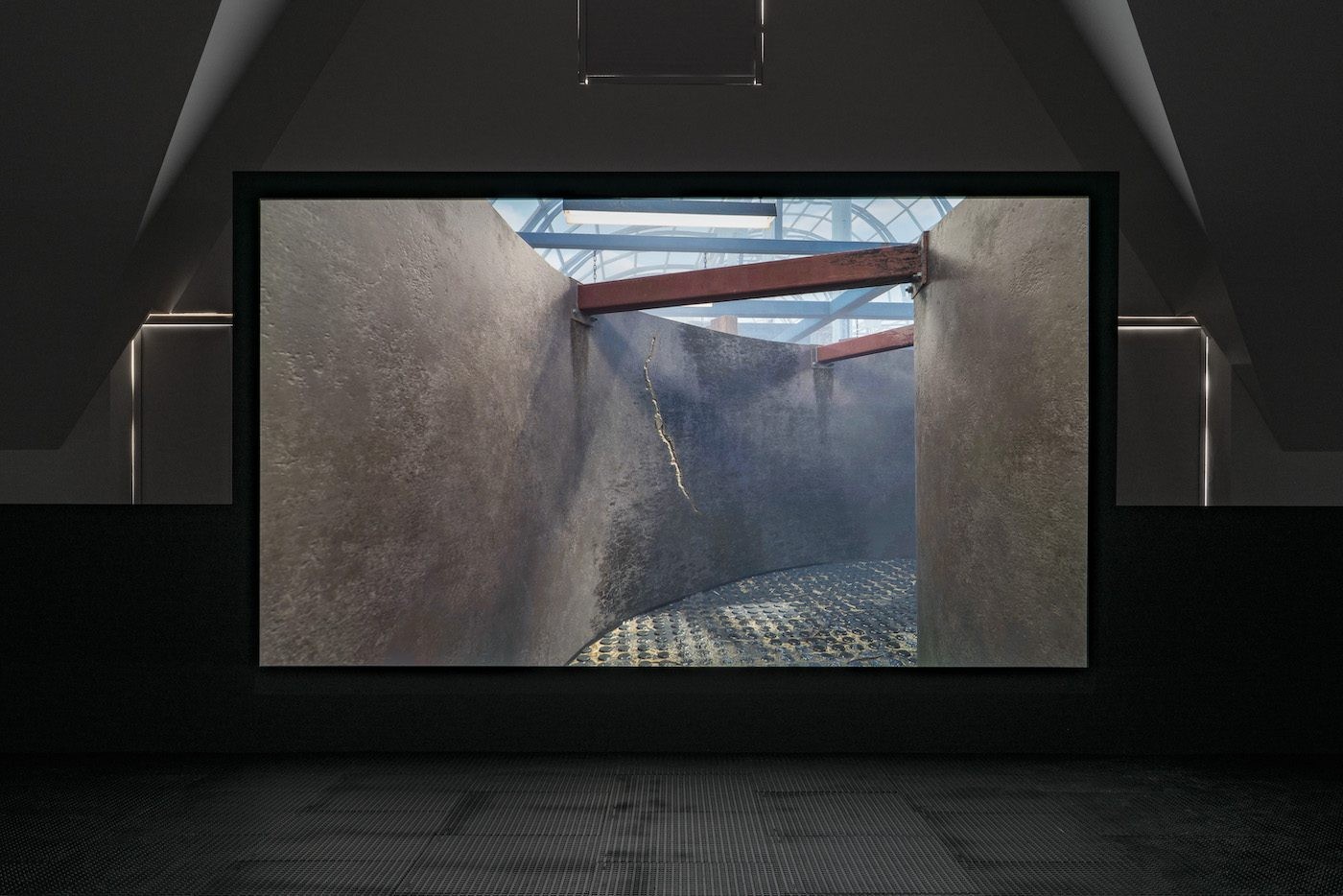

The smell of rubber hits as you push through a pair of swinging industrial doors. Immediately you’re thrust into a cold dark gallery lit by a virtual mise en scéne. With textured rubber matting beneath your feet and a non-Euclidean perspective of a simulated industrialized pasture on screen, a comforting 8-channel melodic composition fills your ears. Finding your metaphysical self occupying a maze of metal fencing, you realize the only way out is through. You are player number one.

The same rubber matting appears on screen, only this time with remnants of barnyard debris tangled between its textured surface. You move hesitantly, gliding through as the metal fencing morphs into an iron Richard Serra-esquemaze. The ambient soundscape soon intensifies and the space grows dark. The aged steel walls transform into cold modern steel – time shifts. A sealed threshold appears, while a steel lever hovers over you. A feeling of doom consumes you as you no longer see glimpses of sky. You were walking the plank all along.

Aria Dean, ABATTOIR, U.S.A.!, Installation view, 2023. The Renaissance Society. Photo: Robert Chase Heishman.

The music continues, and you find yourself spinning in a whirlwind of dark yellow-orange clouds and lighting that flashes across the screen. A sense of pareidolia grips you in the ambiguous haze as you make out faces in its visual chaos. Is this a signal of your metaphysical death? You awaken in a slaughterhouse hell in a pool of your own blood. You rise, experiencing the space as a 3D virtual architectural tour. Your perspective is a lot higher now. A cover version of “I Think We’re Alone Now” plays as you fly through dancing gambrel hooks that hang uniformly, swaying to the melodic rhythms of the heavenly composition. The floor is made of blood, and architectural steel piping litters your peripheral views. The beautifully disturbing simulation ends on a peculiar note.

AAAAND SCENE! –

Chicago’s intimate history with the abattoir – the British/French term for slaughterhouse – makes the city’s South Side the perfect venue for this exhibition. Four point seven miles west of the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, where it is shown, lies the infamous Union Stockyards, the former meatpacking district. A site that exemplifies the industrialization of the slaughterhouse during the nineteenth century’s industrial era, which becomes a contextual thread for Dean’s choice of locale. One may find it hard to believe that the now intentionally hidden slaughterhouse was once open to the public as a “presentation of the modern.” In the late 1950s “it was a spectacle,” writes historian Dominic A. Pacyga. “It drew hundreds of thousands of people a year.” The ugly social history of the Union Stockyards compound leaves behind repurposed architecture and monuments that barely hint at the moral danger of its past. However, Dean’s cinematic genius keeps us cognizant.

Aria Dean, ABATTOIR, U.S.A.!, Installation view, 2023. The Renaissance Society. Photo: Robert Chase Heishman.

Abattoir, U.S.A! is an allegorical recount of the immoral practices of the slaughterhouse as an institution that “educate[s] men in the practice of violence and cruelty,” as a neighbor of London’s Smithfield cattle market told a committee in 1849, quoted by Chris Philo in the book Animal Geographies. Dean brings the slaughterhouse back into the public gaze by contextualizing their own work through Afro-pessimist writer Frank B. Wilderson III as a literal reference, as well as through the idiosyncratic use of first-person video-game perspective. In the journal Social Identities, Wilderson has written that “the death of the Black body is foundational to the life of American civil society.”Just as the death of cattle is foundational to the slaughterhouse? In 2021, discussing resonances between Georges Bataille’s descriptions of base matter and descriptions of Blackness in Afropessimist theory and a long tradition of Black radical thought in November magazine, Dean wrote: “This line of thinking figures the structural position of the Black as outside of but originary to civil society, a necessary sacrifice for ‘whiteness to gain coherence’.”

Through Dean’s critique of the abattoir I am compelled to make connections between chattel and cattle, and their conceptual on-screen architecture illuminates the role society has played in the volatile capitalization of each branding. The connotative notes of patinaed building material glittering in the first half of the video also remind me that Chicago’s architectural landscape serves as an additional layer through which we contribute to the wealth of surrounding institutions – institutions that have capitalized on the violence, desires, and pleasures of enslaved bodies through the “consumption of the poor man’s losses,” as Bataille writes in “The Notion of Expenditure” (1933).

Aria Dean, ABATTOIR, U.S.A.!, Installation view, 2023. The Renaissance Society. Photo: Robert Chase Heishman.

The brilliance of Dean’s work is not just in its implied depiction of physical violence toward the Black body, but in way their world-building capabilities capture the brutalization of the captured body. Dean makes it clear that the slaughterhouse is a location which reveals cultural attitudes toward killing and the socio-economic failures of capitalism. What better place to view this work than on the University of Chicago’s campus, in a city whose daunting urban planning and ongoing labor histories demonstrate said failures daily?

Dean joins a plethora of writers, thinkers, and artists who have theorized the relationship between animals and Black life. In addition to Bataille and Wilderson III, Sharon P. Holland, professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, writes about Black feminist considerations of animal life in the upcoming book an other: “Black life is not solely likened to animal life; it is relational and world-forming with animal lives.” Charles Burnett’s film Killer of Sheep (1978), does something similar as it follows the life of a slaughterhouse worker. In this film, we watch a Black protagonist grapple with the moral effects of his bloody occupation with little option in the way of a better occupation. I uncover a sense of irony as I learn more of the relationship between animals, Black life, and slavocracy.

Aria Dean, ABATTOIR, U.S.A.!, Installation view, 2023. The Renaissance Society. Photo: Robert Chase Heishman.

Dean’s simulated abattoir gave me the fresh breath of air I had felt deprived of. The air I’d been accustomed to was ridden with empty figurative depictions of Blackness and lazy representations of violated flesh. Dean does an exceptional job of creating a world that allows us to experience a quasi-abattoir, allowing for notions of Afro-pessimist theory to be visualized materially. The powerful implicative nature of this work prompts me to grasp just how porous the line between animal and human is in the eye of capitalism. It was violence that made the industrial new world and it is violence that sustains it.

Abattoir, U.S.A! is on show at The Renaissance Society, Chicago from February 25 to April 16, 2023.

Lola Ayisha Ogbara (b. 1991) is an artist, writer, and curator based in Chicago, Illinois. Her practice explores the multifaceted ramifications of being in terms of the Black experience. Ogbara works with clay to emphasize a necessary fragility that symbolizes the essential contradiction implicit in empowerments. Sculpture, sound, design, and installation art also find their way into Ogbara’s interdisciplinary practice. She holds a BA from Columbia College Chicago and an MFA from Washington University in St. Louis.

Plus d'articles de

« Apprendre à Flamboyer » : pratiquer la joie collective au Palais de Tokyo

C& Magazine’s Highlights of 2023 You Might Want to Read Again

John Akomfrah: “If there is a problem with hybridity, for me, it is that it participates in this hierarchization of the world”

Plus d'articles de

A(spora) de Jazsalyn : Sur le corridor Gullah Geechee

Denis Maksaens: Glitch and Representation in the Caribbean