An Exhibition Aims at Accessibility Against a Backdrop of Protest in Kenya’s Capital

17 October 2024

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Mūhunyo Maina

5 min de lecture

Mūhunyo Maina reviews a pertinent exhibition at NCAI in Nairobi, following protests against the 2024 Finance Bill, exploring ways to democratize art viewing.

Nairobi has witnessed a seismic shift in its political atmosphere. From 18 June until 8 August, Kenyans took to the streets of Nairobi to protest the national government’s proposed Finance Bill, which would impose punitive taxes on the country’s poor and middle class and unemployed young people. These protests were largely decentralized, and driven almost entirely by Kenyans on social media. Patriotic citizens, armed with nothing but Kenyan flags and placards, were met with the full arm of the state: beatings, teargas, live bullets, and abductions were meted out wantonly by Kenya’s security forces. In spite of the state’s best efforts, these protests ruptured the norm of Nairobi life. For the first time in recent memory, Kenyans came together regardless of tribal, ethnic, and political affiliations with a single goal: to rise up and protest against the daily injustices suffered by the struggling majority at the hands of a minority of corrupt politicians who are more concerned with lining their pockets with stolen public funds than providing basic services to their electorates.

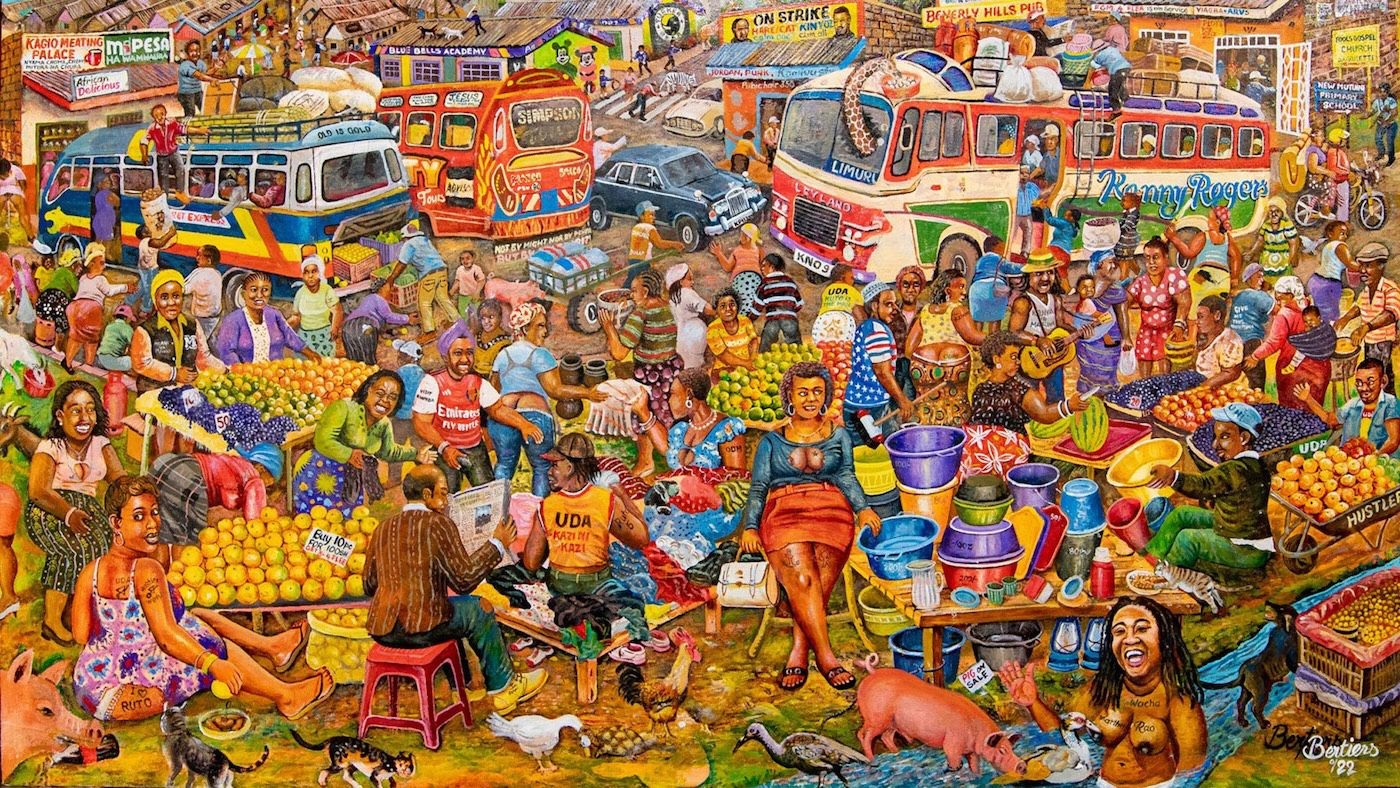

Joseph Mbatia ‚Bertiers‘, A week before the elections, 2007.

Many artists have responded to the disparities between Nairobi’s beleaguered working class and its neocolonial elite. Michael Soi has used anthropomorphism in his work to call out corrupt politicians and government bureaucrats for their predatory looting and uncontrollable greed, portraying them as pigs, alley cats, and stray dogs in his paintings. Joseph Mbatia (aka Bertiers) has masterfully used satire to ridicule Kenya’s elite for more than forty years, often depicting them in farcical situations. Bertiers’ 2022 exhibition Sarakasi za Siasa (Political Circus) derided Kenya’s political class as they campaigned during the last general election. As early as the 1960s, Edward Njenga’s terracotta and clay sculptures retold the struggles of Kenya’s poor working class to make ends meet in a neocolonial capitalist system. Njenga’s 1970 sculpture No Vacancy depicts distraught young men queuing at an unemployment office in Nairobi in search of work; fifty-two years later, the number of unemployed youths in Kenya was “as high as 35% (4.5 million young men and women).”

Installation view of ’60 Years: the NCAI Collection’ at the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute, Kenya.

Among the class disparities that characterize Nairobi, art viewing has long been the preserve of the minority elite echelon of society. Most Nairobi galleries are situated in the heart of suburbia, where foreign dignitaries, diplomats, and the tiny population of Nairobi’s local financial elite live, and the price of procuring artwork in Kenya is often far beyond what most Kenyans can afford. The mediums of communication in these shows are almost always exclusively in English rather than Kiswahili, and the works presented are often discussed using jargon which few outside the art intelligentsia can readily understand. Accordingly, much needs to be done in order to resolve the class disparities that characterize Nairobi art viewing. In August and September, the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute (NCAI), founded by Michael Armitage, put its collection on display in 60 Years: Selections from the NCAI collection. NCAI curator Don Handa saw the exhibition, which was free to view and open to all, as “a moment to come together and think about how to increase visibility, making artwork accessible.”

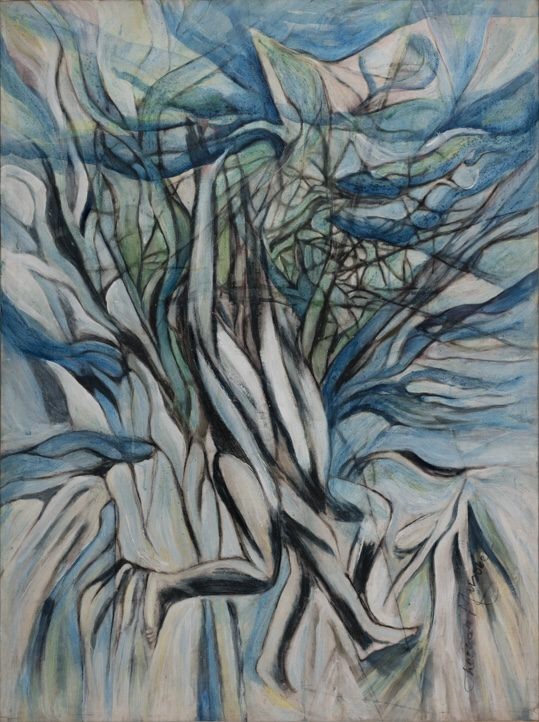

Theresa Musoke, Dancing with the Trees, 1990’s. Mixed Media on Canvas. Courtesy of NCAI.

The collection is extensive, featuring work by artists from across the East African region as well as the wider continent. As well as works by contemporary artists like Peterson Kamwathi, Richard Kimathi, and Chemu Ng’ok, there were a few rare gems of East African art history in the show. It was a pleasure to see works by Ugandan stalwart Theresa Musoke, famous for her abstract expressionist depictions of East African wildlife. In her painting Dancing with Trees presented in 60 Years, enigmatic human forms are beautifully rendered in mixed media on canvas. An undated, untitled painting by Louis Mwaniki, one of Kenya’s first professional painters, working in the 1950s and 60s, and a long-time academic at Makerere and Kenyatta University, was truly a privilege to witness. In spite of Mwaniki’s status as a member of the country’s founding generation of modernists, his work is incredibly hard to find within Kenya, much of it being tucked away in private collections across Europe and the US. Handa laments that much of the work by Kenya’s artists in the past 60 years is held in collections outside of the country. Indeed, Kenyan art has historically been patronized in large part by wealthy expatriates, who often took purchased artworks with them on their return journeys. To redress this challenge, Handa hopes that NCAI will become a center for the East African region where people can engage with Kenyan and East African art at no cost.

Louis Mwaniki, Untitled, N.D, Oil on board. Courtesy of NCAI.

60 Years at NCAI was certainly well curated in an aesthetic sense. Handa organized the various pieces from across the region and continent in a manner that enabled the stylistic and conceptual approaches and themes that link these artists together across time and space to emerge. However, perhaps more could have been done to provide the historical context of the artists and their practices to a lay audience, who would not have been formerly exposed to the work of Louis Mwaniki, Kepha Sempanghi, or Josephine Alacu, for example. It would appear that members of Nairobi’s art scene are growing increasingly aware of the urgent need to promote “the growth and preservation of contemporary art in the region,” which Armitage has stated is NCAI’s raison d’etre. However, it is important that we focus equally on the urgent need to democratize art viewing and art criticism, and make art easily accessible to all members of Kenyan society.

Mūhunyo Maina is an artist and writer from Nairobi, Kenya.

Plus d'articles de

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

I Am Monumental: The Power of African Roots

La Fundação Bienal de São Paulo annonce la liste des participant·e·s de sa 36e édition

Plus d'articles de

MAM São Paulo anuncia Diane Lima como curadora do 39º Panorama da Arte Brasileira

Naomi Beckwith présente l’équipe artistique qui l’accompagnera pour la documenta 16