Dedicated to late curator Bisi Silva, this exhibition at the CCA in Lagos features artworks that give new life to some of Africa’s most popular literary works, such as Daniel Fagunwa’s The Forest of a Thousand Daemons. It’s split into three “chapters” and includes works by Amarachi Okafor, Odun Orimolade, Stacey Okparavero, Rahima Gambo, and Victor Ekpuk.

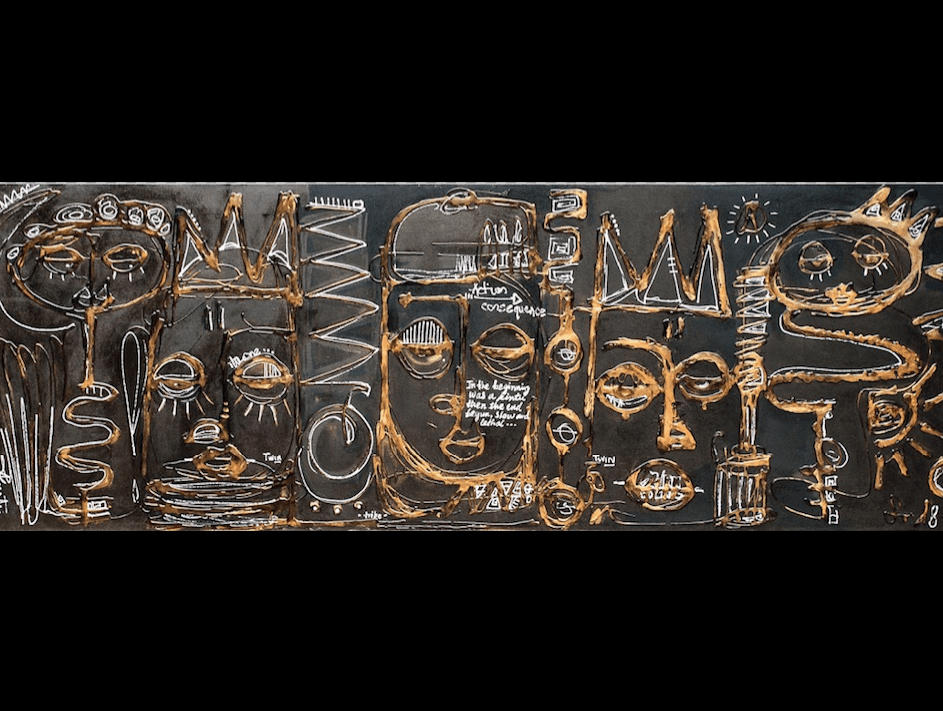

Stacey Okparavero, Kintu, 2018. Mixed media on canvas, 120cm X 45cm. Courtesy the artist and CCA Lagos.

LineGuage is something I had never seen before – or perhaps “read” before, because it possesses the elements of a bestseller. The exhibition is a conversation starter around the rarely discussed continuous co-creation of imagery between African artists and writers over the past six decades. Like a novel, it divides into three engaging and revealing chapters.

The first travels back in time to when a particular kind of creative conjugation between writer and artist began in the city of Ibadan in Nigeria in 1961 – a year after the country’s independence. Mbari Club was a center for cultural activity founded that year by Ulli Beier with Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Uche Okeke, Arthur Nortje, and Bruce Onobrakpeya. Mbari also acted as a publisher during the 1960s and produced seventeen titles; artists in the group had their artworks screen-printed directly onto book covers.

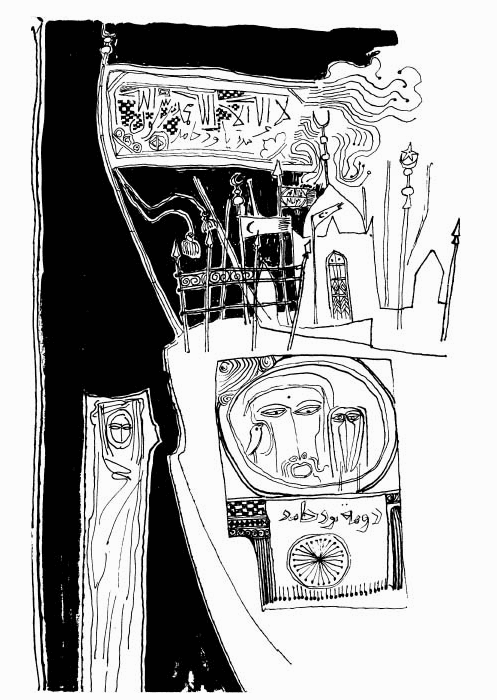

Ibrahim el-Salahi, Three (Facsimiles) Illustrations for “The Wedding of Zein & Other Stories”, 1962. Courtesy the artist and CCA Lagos.

On display are the visual responses of Bruce Onobrakpeya, Uche Okeke, and Ibrahim El-Salahi to classic novels like Cyprian Ekwensi’s An African Nights Entertainment (1962), Daniel Fagunwa’s The Forest of a Thousand Daemons (1938), and Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958).

These artists created images that are mostly abstract, calligraphic, painterly, and sculptural in representation, giving a sense of nostalgia to anyone who has read any of the novels. Sudanese artist El-Salahi also draws from Islamic, African, and European influences to create book illustrations that are uniquely dreamlike, and hard to forget.

For the second chapter, LineGuage shifts gears, moving forward in time to show how artists and books influence each other. Achebe’s family were fascinated by contemporary artist Victor Ekpuk’s artwork and wanted it on the covers of recent editions of the author’s novels.

Even though Ekpuk’s drawings were created at a different time and in different circumstances, they find similar expressions in the authors’ themes. For instance, the cover for No Longer at Ease (1960) is from a series of ink drawings on paper – Lagos Suite was created in 2013 while Epuk was on an artist residency in Nigeria. Ekpuk also uses other media, like collage, for two-dimensional book covers, including Totem of Unconscious (2011) for Arrow of God (1964), and You Be Me, I Be You, 2006 (acrylic on wood) for Things Fall Apart.

Another contemporary artist, Chijioke Onuora, has been producing a series of drawings inspired by Achebe’s Things Fall Apart for over a decade. In his current exploration of batik, he has depicted a war scene and the popular Igbo wooden drums – Ikoro – in reference to their role in the famous book.

Odun Orimolade, Nameless, 2018. Mixed media drawing on paper, 104cm X 136cm. Courtesy the artist and CCA Lagos.

These artists’ inclusion in the exhibition goes deeper than contributing to the narratives created by the writers. It also shows the impact that the philosophies of the indigenous African Nsibidi and Uli art forms have had on the history of book illustration in Nigeria right from 1961, when the Mbari Club started publishing.

For the final chapter of LineGuage, the relationship between art and literature is explored by five female artists whose work engages with storytelling. Amarachi Okafor, Odun Orimolade, Stacey Okparavero, Rahima Gambo, and Jess Atieno respond to Kintu (2014), a novel by Ugandan author Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, who has been dubbed the Chinua Achebe of Uganda. While relating a saga that spans the history of Uganda, Makumbi tells personal stories that address ideas of gender, religion, and mental illness. In responding, the five artists address these themes too.

Rahima Gambo explores the moon in a 10-minute video – The Untold Story of the Moon of Gatonya, 1750 – for which she used the open-source video archives of the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). In the novel, Makumbi makes the moon a character that watches what unfolds from a distance, giving a first-person account of her interior emotions and thoughts during this time in 1750. Gambo’s video interprets the moon’s expressions and sentiments.

Kenyan artist Jess Atieno responds with an installation of inked acrylic plates. It refers to bloodlines and the almost mystical bonds within African ancestry. Stacey Okparavero, through a mixed-media painting and linear sculptures made of found metal, tackles the role of patriarchy in African society.

The bloodline which, in the novel, chains generations of Kintu’s descendants to a curse is captured in an installation of bags and chains by Amarachi Okafor. Like Okafor, Odun Orimolade uses a large drawing and mixed media to elucidate the role and gravity of curses in African culture.

Dedicated to the memory of Bisi Silva, the founder of CCA Lagos who passed away only last month, LineGuage is an exhibition that should be repeated as often as possible, to prompt writers and artists to remain in a state of constant procreation. LineGuage is not just for everyone who loves literature or art, but for everyone who has ever picked up a book.

The exhibition will continue in memory of Bisi Silva until 4 April, 2019 at CCA Lagos.

Based in Lagos, Obidike Okafor is a content consultant, freelance art journalist, and documentary filmmaker.

More Editorial