Tschabalala Self belongs to a new generation of painters depicting a three-dimensional representation of the Black female experience. Our author Sabrina Greig looks into how the Harlem-born artist gives her Black female characters physical and mental agency.

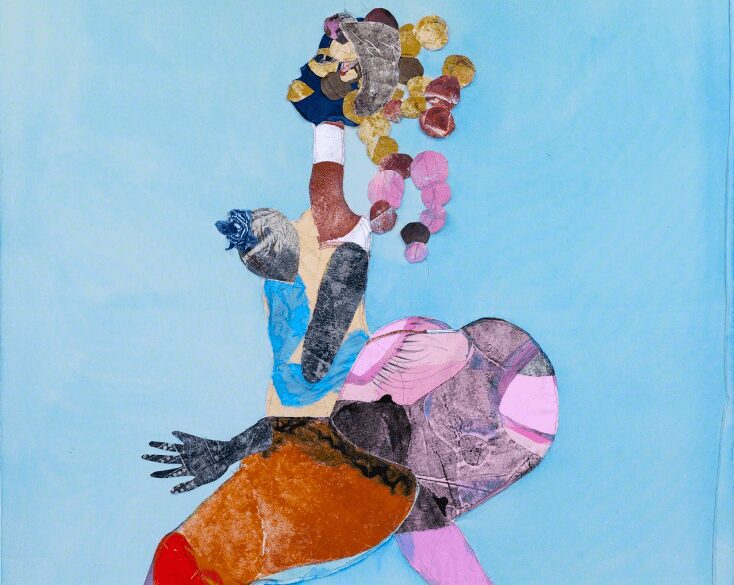

Tschabalala Self, For the Gods (detail), 2015. Courtesy the artist.

The painting Open Casket at this year’s Whitney Biennial sparked age-old debates regarding the issues of power and agency in the telling of the Black experience in art. Historically, it has taken the unique aesthetic of an African-American male artist to break through the mold of contemporary art’s mainstream culture.

Hailing from Harlem, New York, Tschabalala Self is the 26-year-old Yale School of Art graduate who has gripped the art world with an oeuvre that explicitly asserts the perspective of Black women.

Recognized by Artnet and Timeout New York as an “emerging artist to watch,” Tschabalala Self made her solo debut with an exhibition in London at the Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art last January. Her characters—seen leaping, canoodling, and making love—satirize the tendency for popular culture to showcase caricatured portrayals of Black femininity. Self draws attention to the ways in which mainstream culture frequently consumes hypersexualized depictions of Black intimacy, at the expense of more nuanced representations that surpass the physicality of the body. Through a fusion of printmaking, painting, fabric, and collage, she ironically capitalizes on patriarchal notions of womanhood. And in doing so, her work subverts the oppressive effects of misogynist stereotypes on the psyche of a woman.

Tschabalala Self, Installation view at Parasol unit, London 2017. Courtesy of Parasol unit foundation for contemporary art. Photography by Philip White.

For example, two pieces exhibited at the Parasol Unit Foundation, Carma and Cross, present centralized, unclothed figures who dominate the canvas with their bodies. Their provocative postures—one figure squats with her rear-end facing the viewer and the other with her breasts exposed—demonstrate that they are in control of their bodies. Self’s inclusion of subtleties like a flared hand on the figure’s knee in Carma or the coquettishly crossed arms in Cross, make it known that the characters are aware of the male gaze and, as a result, ready to pose.

While she exhibits the nude bodies of women in seductive poses and compositions, the artist incorporates a level of psychological complexity to her characters through assertive gazes and confident postures. She renders her figures as fearless and self-assured in their skin, innovatively pairing audacious promiscuity with mental strength—two qualities rarely afforded to the Black female experience in art.

The uniqueness behind Self’s aesthetic comes from her tactic of dismantling the female form in order to put it back together. This reconstruction of the body through different patterns and fabrics introduces a level of abstractness, granting her characters a surreal dimension. In For the Gods, for example, the figure looks up toward the sky, performing a high kick that extends behind her head in a superhuman fashion. In Spare Moment, the vibrant colors and intentional compartmentalization of the body draw the viewer’s attention to the confidence lying in the figure’s steps as opposed to physical attributes of her shape. Self’s pantheon of characters with such strong personas invites audience members to think deeper about their personal narrative and state of mind.

Self’s characters work to counter dominant narrow-minded tropes surrounding the iconography of Black women, as still common in pop videos, by asserting bodily and mental agency. Her artwork is a testament to the ways in which Black women are rarely granted power when visualizing their physical and psychological vulnerabilities.

Tshabalala Self, Carma, 2016

Fabric, linen, flashe, acrylic and pastel on canvas. Courtesy the artist

The artist is not alone in achieving this. TV shows such as Issa Rae’s Insecure and Michaela Coel’s Chewing Gum are moving away from the rigid perfection of the Black female protagonists as in shows like Scandal and Being Mary Jane. However, all of these varied representations give the icon of the Black woman room for more realistic conceptions that encapsulate the full spectrum of her experience.

Self’s strong focus on portraying non-Eurocentric body types not only celebrates bulbous musculature, but also displays varying representations of self-love. Her aesthetic restores the agency that is often revoked from the widely circulated iconography that visualizes Black women as objects to be consumed, and allows them to revel in the many manifestations that dignity can take on.

Tschabalala’s work is currently on show in the group exhibition « From DADA to TA-DA! » curated by Max Wolf at Fisher Parrish Gallery Brooklyn.

Sabrina E. Greig is an art critic in Chicago, originally hailing from New York City. She received her MA in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on representations of the Black diaspora in pop culture, fine art, and gentrified urban spaces. Her literary work has been published in Fnewsmagazine and Bad at Sports.

More Editorial