In Harare, a cathartic group exhibition celebrates the work of collectives who bridge the gap between a feeble art market and scant resources.

Tinotenda Chivinge, Zimbabwe Bird(s), found objects (variable dimensions). Photo: Nyadzombe Nyampenza

Harare’s thriving art scene would not be what it is without the supportive networks of collectives that exist around the city. The high rate of unemployment in Zimbabwe makes it difficult for most artists to secure a job as a side hustle. Without enough commercial art establishments to engage them, artists can become despondent, and some resort to drugs and alcohol abuse. To keep their dreams alive, struggling artists have turned to each other—coalescing into inspiring and nurturing collectives.

In a first-of-its-kind project, the National Gallery of Zimbabwe (NGZ) in Harare has gathered four visual art collectives from around the capital for a multi-group exhibition titled A Gathering, curated by Fadzai Veronica Muchemwa and Zvikomborero Mandangu. The Animal Farm Artists’ Residency (popularly known as Animal Farm) was founded by Admire Kamudzengerere; Tarisa Visual Art Studio by Gareth Nyandoro; Village Unhu was established by Misheck Masamvu with Georgina Maxim and Gareth Nyandor; and Post Studio Arts Collective by Wallen Mapondera and Merilyn Mushakwe. Other collectives, such as Dzimbanhete Arts and Culture Interactions Trust (DACIT), started by Chikonzero Chazunguza, and Mbare Art Space, set up by Moffat Takadiwa, are not directly represented but their influence over the exhibition is manifest. Nyandoro and Kamudzengerere were mentored by Chazunguza at DACIT before establishing their own groups, and Takadiwas’ success continues to inspire younger visual artists to embrace found objects.

Although they each project a distinctive visual impact, the use of discarded materials is a common thread that runs through work presented by the four collectives. This can partially be attributed to long-standing issues of minimal resources and meager support. Artists looking for materials forage in dumpsters, mingling with stray dogs, vagrants, and poor folks who collect recycling materials for a living. Artists also follow refuse-collection trucks to the landfills where they offload. In the past decade a strong movement has developed out of the initial impetus, superseding conventional notions of resourcefulness.

Exhibiting with Tarisa Art Studio, artist Wilfred Timire uses polyurethane bags, which are considered the most humble of materials by people living in poverty. After their initial use carrying and storing goods, polyurethane bags are repurposed many times and only abandoned when worn out. Timire’s eye for color and design allows him to combine them through stitching and drawing into engaging visual narratives. Characters emerge in his work to tell observant stories of urban life that contain biting social commentary. One of his works, Tsomutsomu, is a head-and-shoulders portrait of a young man depicted from the back. The subject wears opaque sunglasses and turns furtively over his shoulder. His apparently uncertain behavior is reflected in the Shona title—a colloquial term for somebody who is running either after or from something.

Tinotenda Chivinge, Shiri dze Mudzimu, found objects (variable dimensions).Photo: Nyadzombe Nyampenza

Zimbabwe Bird(s) by Tinotenda Chivinge is a satirical take on the bird featured on Zimbabwe’s national flag, while Shiri dze Mudzimu, which translates as “the ancestors’ birds” hints at sightings of certain birds that are perceived as good or bad omens in traditional Zimbabwean beliefs.

Clive Mukucha’s work titled Dhunamutuna, which is a Shona word for Europeans or white people, is a spectral representation of the colonizer whose negative impact continues to be felt in postcolonial Zimbabwe. His quilted piece Insurgence-Hondo mu Mozambique invokes battle-worn combat gear with reference to Mozambique, whose war for liberation was intertwined with Zimbabwe’s own.

Tawanda Reza, Kubasa kwababa kune basa, mixed media on canvas (300X340cm). Photo: Nyadzombe Nyampenza

Using found textiles and polyurethane bags, Tawanda Rezas’ cut-out figures are stitched onto background material to show an industrial scene where four people are busy at work. The title, Kubasa kwababa kune basa, has a double meaning that suggests that there is a lot of work at his father’s job and that he is being exploited.

An interesting contrast exists between work from Animal Farm and that from Mbare Art Space. Inspired by Korekore basket weaving, Takadiwa at Mbare Art Space focuses on color, form, shape, and other design elements. In his work with toothbrush heads, a viewer may no longer see them as such. Their colored bristles become waves of color and texture painting abstractions of Zimbabwe’s post-colonial history. Unlike most of Takadiwa’s output, the Animal Farm artists create works that retain a raw energy due to their original properties that are not erased through concept. The bare objects sometimes look as if they might crumble back into a pile of junk if their bonds fail to hold.

At Post Studio Arts Collective, Pardon Mapondera is not content to let the objects speak for themselves. In combining materials, the artist attempts to take them through a process of metamorphosis. His forceful methods involve applying heat and punching holes to glue surfaces to each other. Mapondera’s dark side is revealed as the tortured objects manifesting from his hands exude a humanoid essence. Muoneri is a tangled mess of cylindrical objects and string that gives the ghostly outline of a bespectacled figure invested with prophetic vision. Vaoneri II is a shattered skull with a missing jaw and one eye, which in spite of its damage and trauma, is presented as an embodiment of a powerful spirit that sees what lies beyond.

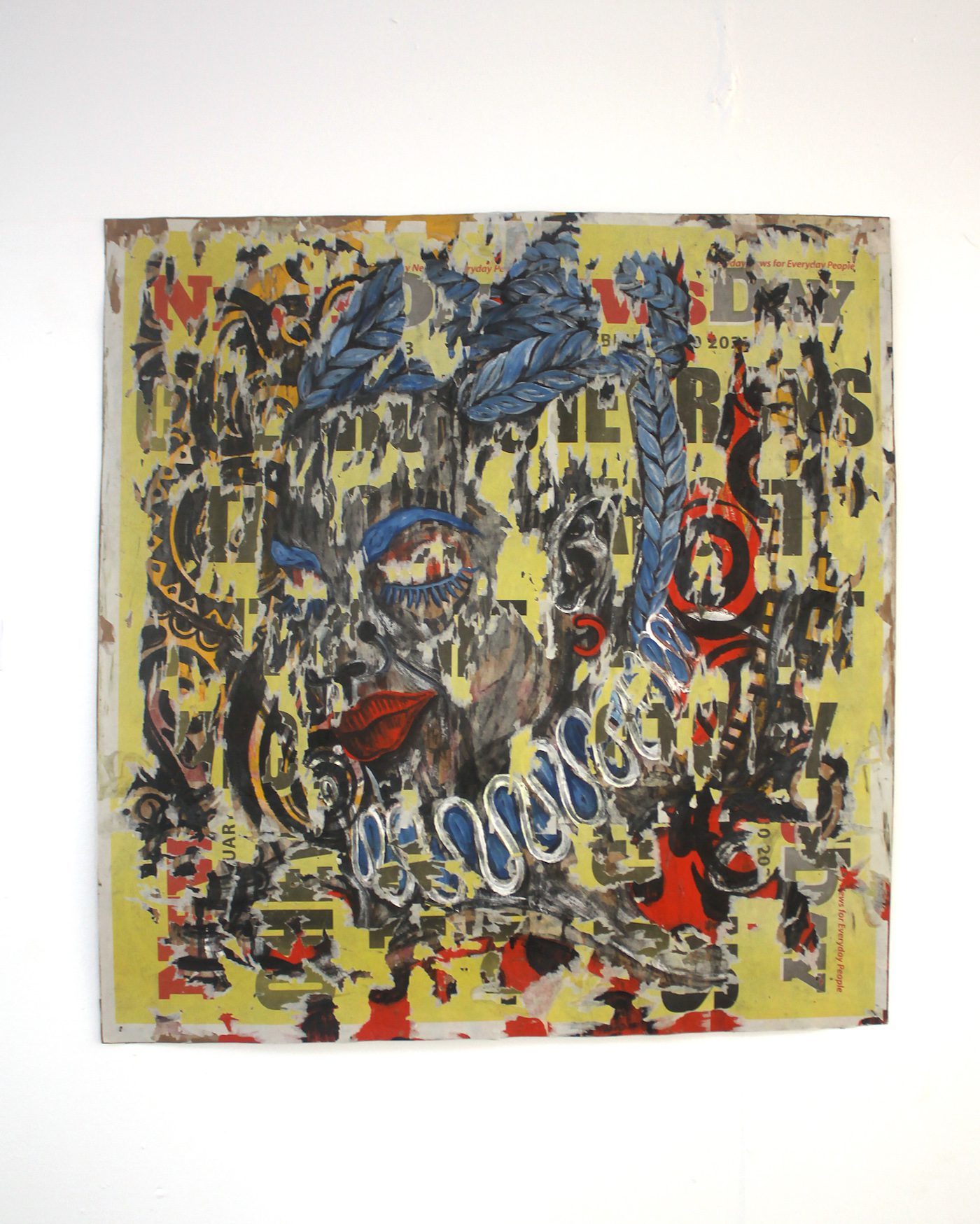

The kind of raw material available to some may not be easily accessible in the affluent suburbs of Harare, which has better services for refuse collection and which is where Village Unhu is located. The only things left in the streets are banners from newsstands, which one member of the collective, Evans Tinashe Mutenga, rescues for his collages. His triptych Mindset is created through a process of drawing, layering, scratching, and peeling. The subjects of his works, often mythical beings embodying animal and human qualities, remain between a state of concealment and revelation.

Evans Tinashe Mutenga, Mindest, mixed media collage. Triptych, (161X153cm). Photo: Nyadzombe Nyampenza

Bridging the gap between a feeble market and scant resources has inspired Zimbabwean artists to bond and discover new possibilities in the found object. The transformation of decaying materials into complex assemblages deeply resonates with these communities’ struggles and scars. Redemption of what was forsaken is a compelling analogy that encourages faith and hope.

Nyadzombe Nyampenza is a photographer and conceptual artist. His work is based on exploring his city Harare through documenting activities and the spaces. Part of his work involves telling urban stories with staged narratives, and self-portraits.

GIVING BACK TO THE CONTINENT

More Editorial