The traces of racialised enslavement can be found in various German cities. The artist’s exhibition follows them through Frankfurt am Main.

Cameron Rowland, macandal, 2023 Oxalic acid 37.5 x 30.5 x 67 cm Packets of materials that could invoke spirits, protect against punishment, and poison slave masters were called macandals. They were at the center of a plot in 1757 to poison all the white people in Haiti. The plot was organized by hundreds of enslaved and free black people. All macandals were subsequently outlawed. Their trade and use continued despite their criminalization. Enslaved people throughout the Atlantic world used arsenic, manioc juice, ground glass, and oxalic acid to poison overseers, masters, masters’ children, and livestock. Oxalic acid is a stain remover and household cleaner.

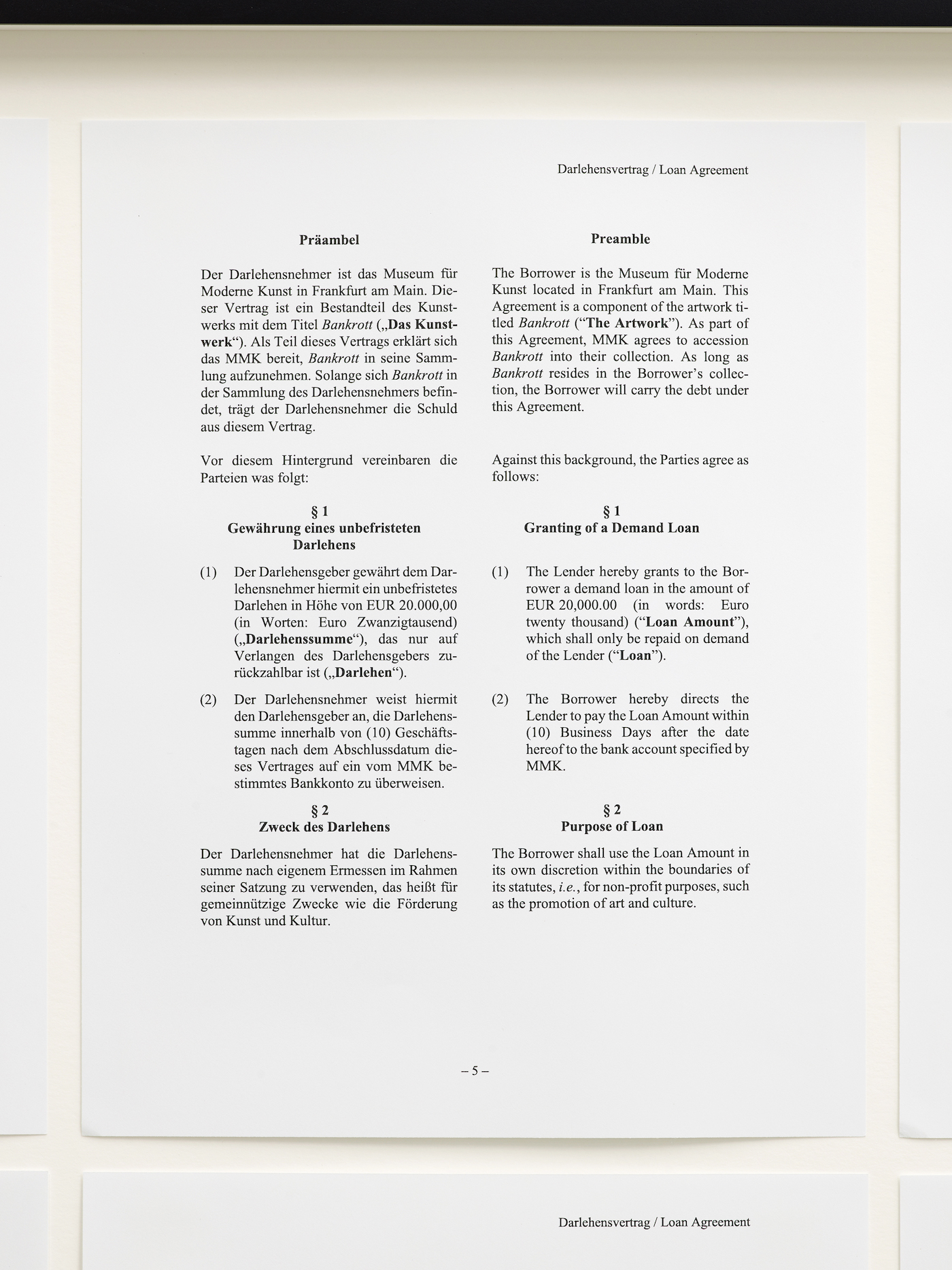

In twenty-five years, the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt will owe Cameron Rowland 1,256,518.73 Euros. This is the amount that the sum of €20,000, which Rowland lent to the museum as part of his exhibition Amt 45 i, on view at TowerMMK , will generate at an annual interest rate of 18 percent. More specifically, the museum will owe this money to the corporation Bankrott Inc., which Rowland founded and also directs. The legally binding loan agreement, which is an element in the artwork Bankrott (Bankruptcy, 2023), and can be viewed, page by page, in the exhibition. Although the life of the loan is indefinite, the table included as an annex to the contract gives an overview of how the debt will develop up to the year 2122. By that year the MMK will owe the corporation €311,591,692,053.27 – an astronomical sum that would currently exceed the economic output of the entire metropolitan region of FrankfurtRhineMain.

Cameron Rowland

Bankrott, 2023

Indefinite debt

Reparations were paid to slave owners. Compensated emancipation allowed slave owners to retain the value they had assigned to the lives of slaves in addition to the profits they had extracted from slaves’ labor. Compensated emancipation in Haiti, Brazil, Cuba, Washington D.C., the British colonies, the Danish colonies, the Dutch colonies, and German East Africa paid slave owners for their loss of enslaved property. Slave owners and their financiers were provided monetary compensation, high-interest debt obligations, and indentured servitude as repayment.

British compensation payments fueled the growth of British financial institutions that held outstanding plantation mortgages including Barclays, Lloyds Bank, and the Royal Bank of Scotland. The Haitian compensation debt, originally paid by formerly enslaved people to French slave owners, has been bought and sold by numerous banks including Crédit Industriel et Commercial, Crédit du Nord, Citibank, and ODDO BHF. These compensation payments continue to grow within European banks alongside the profits of the slave economy. The value of slave life, labor, and reproductive capacity remains integral to European financial institutions, corporations, universities, museums, and governments.

Frankfurt am Main is the monetary center of the eurozone and houses offices of nearly every major European financial firm. The concentration of financial firms in Frankfurt am Main has enriched the city since the 17th century.

A loan of 20,000 euros was issued to the Museum MMK für Moderne Kunst from Bankrott Inc., a company created for the purpose of holding an indefinite debt. Because it is a demand loan, no payments can be made until the lender demands repayment. Bankrott Inc. will never demand repayment. The debt will accrue interest indefinitely. It will increase at a rate of 18 percent each year, the highest rate legally allowable. The Museum MMK für Moderne Kunst is a city government department, Amt 45 i. For this reason this debt is owed by the city of Frankfurt am Main.

As reparation, this debt is a restriction on the continued accumulation derived from slavery. As a negation of value, it does not seek to redistribute the wealth derived from slave life but seeks to burden its inheritors.

It is a debt that Rowland wants to put in relation to the capital accumulated from enslavement in Frankfurt. For, as Rowland explains in a detailed and informative text included in a publication realeased in conjunction with the exhibition, Frankfurt am Main owes its status as Germany’s financial center and the hub of monetary policy in the Eurozone to an economic system that profited from the exploitation of enslaved persons during the colonial period, the effects of which determine our reality today. From the seventeenth century onward, the Frankfurt Stock Exchange traded the shares of mercantile companies instituted under the slavery-based system. During that period, banks were also established in the city. The Bethmann Brothers Bank was founded in Frankfurt in 1748 by the Bethmann family and financed companies that were active in the transatlantic slave trade. Commerzbank was established in 1870 in Hamburg. Now headquartered in Frankfurt, Commerzbank was formed when certain well-known trading houses, merchant bankers (credit institutions), and prestigious private bankers merged to create a universal bank operating as a stock corporation.

Rowland’s work Omission (2023) is a graphic representation of the Commerzbank’s corporate history – a visual account that can also be found in the Historical Museum Frankfurt. Using dates, names of entrepreneurs, and takeovers, the graphic illustrates the bank’s history at a glance, and Rowland has added any omissions from the official history in the accompanying publication, such as the names of the founders, whose immense fortunes were derived from slavery and colonial business. They include Carl Woermann, Conrad Hinrich Donner, Carl Georg Heise, the brothers Ludwig and Gustav Amsinck, Emile Nölting, and Theodor Wille. William Henry O’Swald’s company specialized in the trade in cowrie shells – one of the currencies used to buy enslaved persons. When enslavement was abolished, it was not the enslaved people who received reparations but the people who had owned them. As Rowland puts it, “Compensated emancipation allowed slave owners to retain the value they had assigned to the lives of slaves in addition to the profits they had extracted from slaves’ labor.” The financial system also benefited from the end of enslavement.

Cameron Rowland

Public Use, 2023

Museum für Moderne Kunst, Tower MMK entryways and exits

The building located at Taunustor 1 was developed by Commerzbank and Tishman Speyer. To fulfill the city of Frankfurt am Main’s public use requirement, the developers contracted with the Museum für Moderne Kunst to include a location of the museum on the second floor of the building. The developers agreed to subsidize the museum’s rent and utilities for 15 years.

Museum für Moderne Kunst was one of the 15 cultural institutions created in Frankfurt am Main between 1968 and 1994 that became part of the city’s Museumsufer project. Between 1950 and 1992, the city’s cultural funding budget grew nearly twentyfold. City taxes on financial firms fueled cultural development. Cultural development was used to attract workers to expand the city’s financial sector.

Museum für Moderne Kunst, Tower MMK is a public museum inside of a private office building in the banking quarter. Tower MMK materializes the relationship between Frankfurt’s public cultural development and private financial development. Tower MMK is subsidized through the rent paid by the numerous financial corporations located in the building. These include inheritors of the profits of slavery: Barclays, Schroders, J.P. Morgan, and Credit Suisse.

Frankfurt am Main has been the financial center of Germany since the 17th century.

Tax revenues from the financial sector made Frankfurt, and thus its art institutions , beneficiaries of the capital amassed from racialized enslavement . As part of his intervention Public Use (2023), Rowland ascertained that the city’s budget for cultural promotion grew almost twentyfold between 1950 and 1992. This money was used to build fifteen cultural institutions in Frankfurt between 1968 and 1994, among them the MMK. Public Use makes specific local references to the TowerMMK, whose exhibition space of 2,000 square metres became an additional museum venue in 2014. It is housed in the new building complex known as TaunusTurm. Public Use expands the already gargantuan TowerMMK by providing access to the entrances and exits of areas that are otherwise closed to the public. Visitors can now pass through the museum’s connecting spaces into the two-part building complex. They can get their own sense of how TowerMMK, a public museum, is housed in a private office building in the banking district. TaunusTurm was designed by Commerzbank and Tishman Speyer. As Rowland explains, the MMK moved in there to enable its sponsors to fulfil their economic responsibilities and satisfy Frankfurt’s public use requirements as stipulated by the city government. “Tower MMK is subsidized,” Rowland elaborates, “through the rent paid by the numerous financial corporations located in the building. These include inheritors of the profits of enslavement: Barclays, Schroders, J.P. Morgan, and Credit Suisse.” Some of the few exhibited objects in the exhibition are also associated dense with information about business dealings involving racialised enslavementin cities like Frankfurt and Osnabrück. Some objects address the ways in which enslaved persons resisted their enslavers, be it through poison attacks, traps, or tools turned to improper uses.

Cameron Rowland

Bankrott, 2023

Indefinite debt

Reparations were paid to slave owners. Compensated emancipation allowed slave owners to retain the value they had assigned to the lives of slaves in addition to the profits they had extracted from slaves’ labor. Compensated emancipation in Haiti, Brazil, Cuba, Washington D.C., the British colonies, the Danish colonies, the Dutch colonies, and German East Africa paid slave owners for their loss of enslaved property. Slave owners and their financiers were provided monetary compensation, high-interest debt obligations, and indentured servitude as repayment.

British compensation payments fueled the growth of British financial institutions that held outstanding plantation mortgages including Barclays, Lloyds Bank, and the Royal Bank of Scotland. The Haitian compensation debt, originally paid by formerly enslaved people to French slave owners, has been bought and sold by numerous banks including Crédit Industriel et Commercial, Crédit du Nord, Citibank, and ODDO BHF. These compensation payments continue to grow within European banks alongside the profits of the slave economy. The value of slave life, labor, and reproductive capacity remains integral to European financial institutions, corporations, universities, museums, and governments.

Frankfurt am Main is the monetary center of the eurozone and houses offices of nearly every major European financial firm. The concentration of financial firms in Frankfurt am Main has enriched the city since the 17th century.

A loan of 20,000 euros was issued to the Museum MMK für Moderne Kunst from Bankrott Inc., a company created for the purpose of holding an indefinite debt. Because it is a demand loan, no payments can be made until the lender demands repayment. Bankrott Inc. will never demand repayment. The debt will accrue interest indefinitely. It will increase at a rate of 18 percent each year, the highest rate legally allowable. The Museum MMK für Moderne Kunst is a city government department, Amt 45 i. For this reason this debt is owed by the city of Frankfurt am Main.

As reparation, this debt is a restriction on the continued accumulation derived from slavery. As a negation of value, it does not seek to redistribute the wealth derived from slave life but seeks to burden its inheritors.

Like many other artworks that have expressed crtiticism of institutions in recent decades, Rowland’s work successfully brings into focus the problematic economic structures that to some extent made it possible for museums to exist in the first place. As a contractual agreement, Bankrott goes even further. In playing its part in the process of making reparations for enslavement, the museum will become so heavily indebted that in the long run it will bankrupt itself, and probably the city of Frankfurt too. Rowland writes that for him it is not a matter of “redistribut[ing] the wealth derived from slave life but seek[ing] to burden its inheritors.” He seems to have calculated a realistic figure for the liability—one that can act as a counter to the capital accumulated through enslavement.

Cameron Rowland: Amt 45 i at Museum MMK für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt runs through 15 Oct 2023.

Gürsoy Doğtaş is an art historian at the University of Applied Arts (“Angewandte”) in Vienna.

"AUF DEUTSCH"

More Editorial