In his exhibition Set It Off, Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste investigates the relationship between sound, Black cultural traditions, and the body

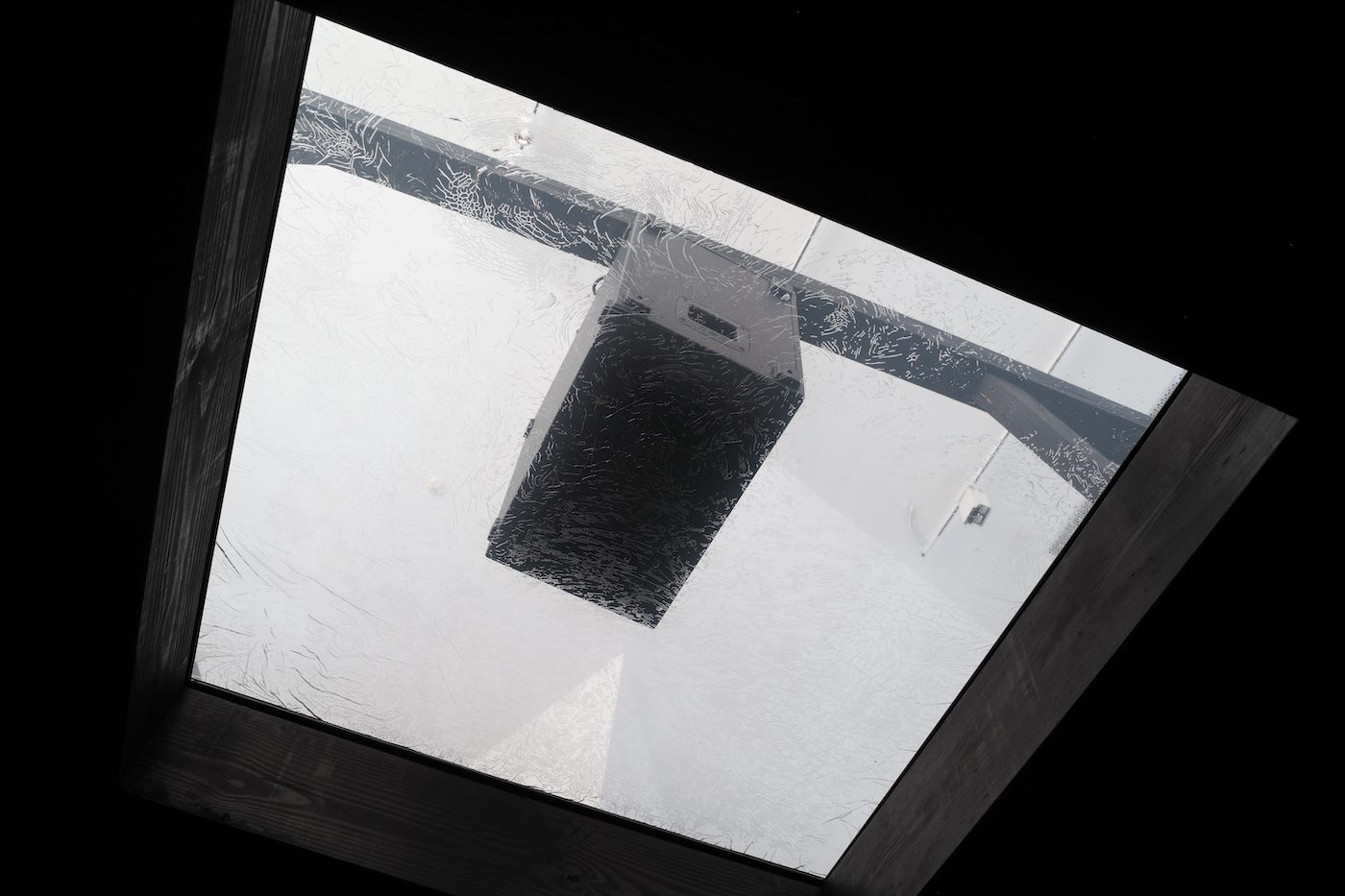

Detail view of Jeremy Toussaint- Baptiste, "Get Low (The Fall/The Drop)", 2021, wood, polyethylene and tinted glass. Institute for Contemporary Art at VCU. Photo by David Hale.

Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste approaches art through carefully constructing active moments of reflection. His practice is a considered one, in which bodies and vibrations moving in space elide with other temporalities. We spoke recently about his multi-site exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University and 1708 gallery, Set It Off.

Detail view of Jeremy Toussaint- Baptiste, « Get Low (The Fall/The Drop) », 2021, wood, polyethylene and tinted glass. Institute for Contemporary Art at VCU. Photo by David Hale.

Contemporary And: I was at the Julius Eastman event at Berkeley Art Museum in 2012, so I’m slightly familiar with his 1979 Evil Nigger composition. Tell me about how the performance you made with LaMont Hamilton, Evil Nigger: A Five-Part Performance for Julius Eastman (2018), came to be – especially in regards to touch?

Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste: In that work, it felt really important to think of presence as a positive and a negative thing, so when bodies aren’t temporally present, there’sa negative presence that isn’t quite an absence.

It’s really interesting that you bring up touch, because I try and avoid touch a lot – I’m not super comfortable with being touched. I don’t bring it into much of my performance work, but with this particular work we were exploring the tensions between gesture and representation and the mess that gets made of all that – the legibility and illegibility. Touch became really important, working with Shantelle Courvoisier Jackson and Nyugen E. Smith, to cultivate a sense of both agency and care. We wanted to trust how they would work with one another, so we didn’t choreograph that piece. How touch between two people showed up was quite genuine and not overdetermined. Especially when working with two Black bodies on a white platform, there’s a danger in telegraphing this sort of affection or disaffection between people as opposed to letting whatever happens come up and let that moment be whatever it is between those two people.

And there’s this other element of touch where they’re touching materials – that that’s where I get really excited thinking about touch, thinking about the materiality and physicality of the shit you’re touching, and how quickly the tactile becomes the sonic. I think you see this especially when Nyugen and LaMont are working with this paint that is touchy, and what is tacky is also very smacky. He’s dripping water, touching the materials in the bowl, and their voices – the vocal cords rubbing together or breath passing between vocal cords – are a touch of some sort that’s bringing forth the sound out of the bodies.

All performance of music is choreographic. I play and studied classical saxophone, and it’s very, very specific when you’re translating notes on a page into sounds, your body has to do specific things that are incredibly choreographic. It’s also touch, you’re manipulating how you’re touching this object and engaging with it. Maybe touch has always been quietly there in how I approach thinking about sound in general.

Detail view of Jeremy Toussaint- Baptiste, « Get Low (The Fall/The Drop) », 2021, wood, polyethylene and tinted glass. Institute for Contemporary Art at VCU. Photo by David Hale.

C&: There’s a transformative potential in sound as touch and the relationship it has with the body. I’m really curious about your current exhibition at the ICA at Virginia Commonwealth University, Set It Off, because of the relationship that sound has with Black cultural traditions but also with the body – that sense that we have when we’re almost absorbing the beats, the bass. Could you tell me about Set It Off?

JTB: The title is pulled from and referencing the film [Set It Off (1996) by F. Gary Gray]. Sound is a material that we can craft with and so is language, and there is a linguistic history there. So Set It Off as a set of words, not as a command but an invitation to some shit, feels like it’s sitting within a Black tradition, not specifically American, because I’ve been listening to some Black UK shit, which has been a part of my life since high school – I was a raver and always into jungle beats. So a certain type of bass culture has always been with me.

The song Set it Off (1984) by Strafe – sampled by so many people, Tupac, Dean Blunt, and others – shows up in lots of different ways vernacularly, and it’s like an invitation to do something that disrupts an existing mode or paradigm, to shake something up. On a one-to-one level, low-frequency cars driving down the street, cars setting off other cars. But also I’m thinking about what are the ways in which low frequency is shaking things, shaking structures, shaking what might we be able to do with history. Taking the reality that bass shakes things and not wanting to make work that is explaining reality, it becomes: Do I use this very real thing to answer a set of unanswerable questions? What else is the bass shaking up or setting off?

In this case, the exhibition uses a lot of water from the James River in 1708 Gallery, in Richmond, Virginia, a deeply traveled space, a massive site of human trafficking during the transatlantic slave trade. Of course, the property that was bodies that were deemed useless were likely thrown into that river. Like many gravesites around the city, the river is a site of mass death to the point that I don’t think it’s worth trying to speculate on how many bodies are there. There’s something scarily challenging about the unquantifiable amount of loss in that water, but there’s also an unquantifiable amount of history in that water. If we’re willing to extend a sense of grace and understanding of reality and materiality to plastic, then we can say that it is omnipresent in our acquired food sources and in our water, to the extent that the many bodies of history are in the water sources. Think about New York and the Ashokan Reservoir – Indigenous people were there, and when it was “settled” that community was flooded to create the water source for New York. So there’s constant loss and displacement when you look at what it takes to create or sustain water sources in places that aren’t designed for large amounts of people to be drinking water.

There’s a lot of history in the water. Almost working with the inverse of Marxist historical materiality, we can say not that the history makes the materials, but that the materials make the history. The bodies in the water create the history, the shit around us creates the bodies who were once property, invested material creates that history and imparts a certain trajectory to it. So with that what can I do with bass? Knowing that low frequency travels faster through water than it does through solids on a conceptual or just an imaginative level, what can I do that’s not trying to make a grand statement but that leaves space for questions?

C&: How did you go about approaching the architecture of the space?

JBT: Those structures are a departure from previous works. The structures at the ICA are part of a series called Get Low. The sun is coming through the sunroof, the perspective is always shifting depending on how the earth is doing its thing. Listening is active. When people ask about the performative aspects, I see that the listeners are active, they’re activated.

C&: It’s a reciprocal practice.

JTB: It’s not just getting into a deep meditative space. You’re walking around the structure, you’re looking at it changing based on where you’re standing, and you’re invited to continue that investigation. Performing wouldn’t be more active – it doesn’t need a performance, the invitation is already there. In the 1708 Gallery you walk around the infinity pool, the water is overflowing and cycling back into the pool and rippling with the bass, and the perspective of it is intended to get people to look all the way behind the structure – you’re invited to continue looking at the world because of where the windows are. It’s like excitement in calculability: I’m facing infinity and I keep looking outside – like it might seem as pedestrian as shit out there, but keep looking. There is a multiplicity – depending on who is there and the time of day, it will change how you experience it. I think that’s true of all work, but I want to make it explicit.

Detail view of Jeremy Toussaint- Baptiste, « Get Low (The Fall/The Drop) », 2021, wood, polyethylene and tinted glass. Institute for Contemporary Art at VCU. Photo by David Hale.

The black square shows up in all of my work and here the structures are all squares or cubes. What’s exciting is that the structures at the ICA and at 1708 Gallery look so dramatically different and function differently logistically and conceptually, but they’re working with the same economy of materials. A subwoofer, water, pool liner, car tint, paint – it’s really quite bare-bones.

It takes that zero point of art from 1915 [when Kazimir Malevich painted his first black square], which got really messy when they discovered that text [in 2015 art historians detected under the black paint a sentence: “Battle of negroes in a dark cave”]. It looks at that text, and thinks maybe that’s a site of excitement, that there’s something exciting about being in a dark cave and refusing the allegory of the cave refuting that light. How many ways can I build a cave, how many shapes can the cave take, how many spaces for ultimately divergent and convergent modes of the radical? The darkness isn’t a stand-in for race, it’s like what happens when nobody can be anything because we can’t see or be seen in the things – what does that open up imaginatively? And then, also, how does it act as an umbrella space – what if it was Latinx battling in a dark cave or people from the island of Dominica battling in a dark cave? There are many groups that could stand to have difficult and necessary conversations in a quiet cave-like setting where questions keep getting asked and it’s not about finding the “aha” moment.

Set It Off is at Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University and 1708 Gallery until June 19.

Nan Collymore is a writer and an inter-disciplinary artist. She is interested in the body and land, and how the two co-exist. Her work is an attempt at creating a language that re-imagines the body as land and as a corporeal topography. She is the founder of small publishing house L’Habillement and lives in New York.

C& SPECIAL EDITION #DETROIT

More Editorial