The artist explores Sweden’s iron production and its connection with the transatlantic slave trade in a solo exhibition at Whose Museum Malmö.

Sweden is known for its strong governmental principle of public access to information,[1] but the country’s available archives are far from complete. In empty files, the image of its neutral position during the two world wars and further back trembles slowly, while successful trade in iron, granite, wood, and now long-distance weapons and streaming media services makes one thing clear: Sweden’s international engagement relies heavily on extraction. This fact concerns the still ongoing colonization of Sápmi in northern Scandinavia, where waters, woods, and ground are demolished for southern and international use, but also points at the long history of Sweden’s persistent trade relations, which disproves its supposed innocence.

Ina Nian’s solo exhibition The Weight of Silence, curated by Black Archives Sweden and hosted by the art collective and exhibition space Whose Museum in Malmö, traces Swedish iron ore exports through various archival gaps. Locating any notes on Sweden’s investment in imperialism in its official history was hard, but the artist found out that certain mining districts provide a rare, strong kind of iron, perfect for chains, and that special welding techniques were imported for exactly that purpose. Looking further into the matter, Nian opened a pandora’s box of Swedish involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. This mostly unwritten history lies like a thick, silent layer over the exhibition: Sweden has always had connections to slave ships and extinction camps, frequently exporting granite, wood, and iron for such uses.

As curator Lisa Rosendahl pointed out with the 2019 and 2021 editions of the Gothenburg International Biennale for Contemporary Art, Sweden’s acquisition of the South Caribbean island of Saint Barthélemy from the French in 1784, in exchange for a small lot in the harbor of Gothenburg—along with tax-free trading rights in the city—secured free trade between France and Sweden during the peak of colonialism. While Rosendahl focused on commissioning sketches for possible memorials for that now forsaken site in a de-industrialized part of today’s Gothenburg, Nian’s artistic investigation approaches the iron trade from the perspective of iron’s slow oxidation under water. The artist wants to know what the materiality of iron can tell us about the historical relations it carries, inviting spectators to engage with that question from the perspective of their own relationship to Sweden’s much-touted social welfare, its self-described neutrality, and its ongoing racial violence.

I am myself from southern Sweden, where universities and trade offices replaced the brutality of extraction sites and delivery locations centuries ago. The thick silence that covers the exhibition space is therefore also my family’s and consequently my own – it is a sonic layer that Nian counters with the sound piece Black Noise #3 (2020). Its frequency is close to zero and it enlaces objects and spectators in the space, demanding that they pay attention not only to what is visible to mere sight, but also to the consequences of an ocular-centric engagement with history.

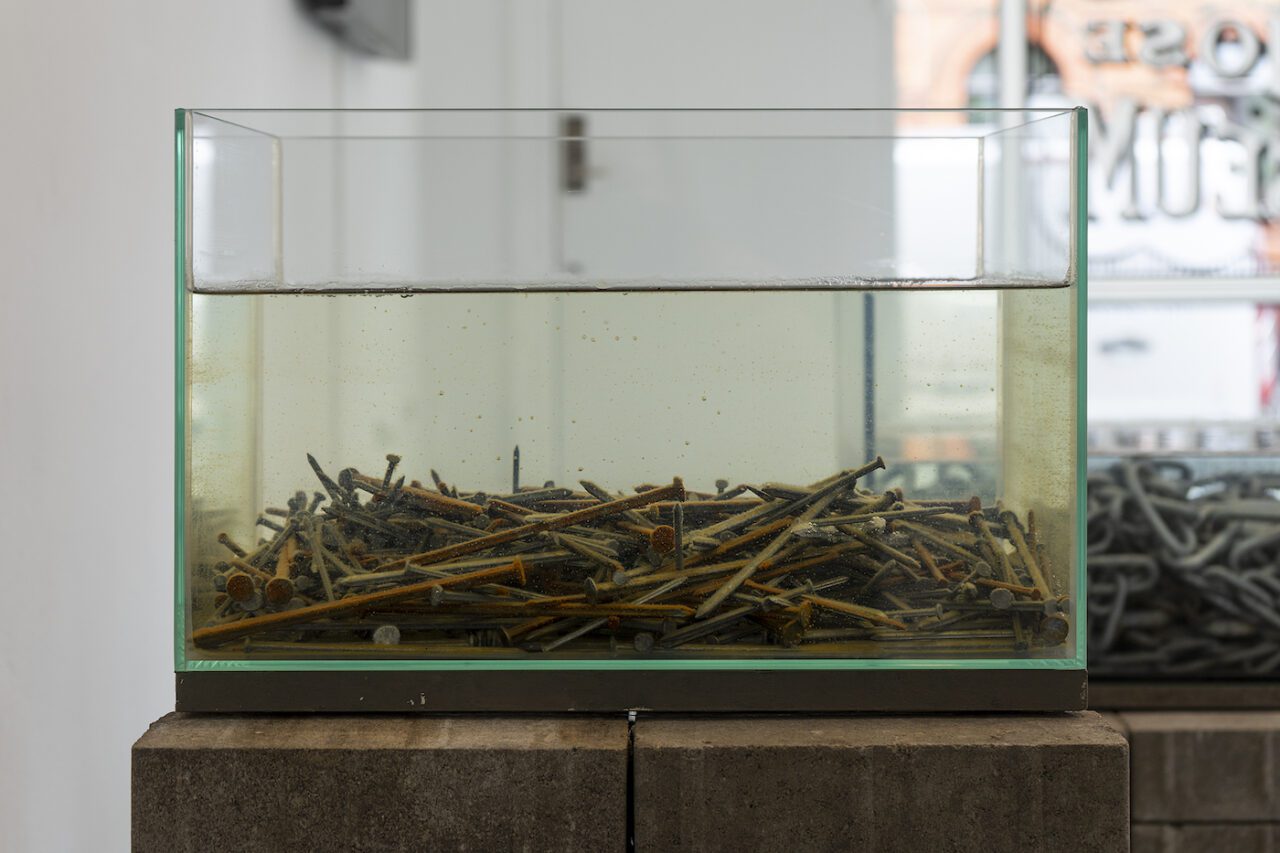

In three aquariums, bubbles of oxygen slowly digest the iron chains, artifacts, and tools that rest wordlessly on the bottom of each. The sea water, carried in from Malmö’s surrounding ocean, slowly shifts in color as the cold grey metal turns green, red, and brown during the duration of the exhibition. This work, Black Noise #4 (2021), gestures to the weight of history sunk at the bottom of the seas. From the oxidation of these material traces, air rises to the surface and utters the layers of relations that still encompass seas, land, and people. In an accompanying sound piece, Nian brings the viewer to witness the preparation of the raw material and its transportation over land and water. A looping rhythm distorts the broken linearity of present archives, interlinking the sounds of wooden ships and those of contemporary fighter planes. From northern mining sites to the two main industrial harbors for iron trading in Stockholm and Gothenburg, my physical memory of Swedish railroads comes to be soaked in a different kind of time.

High volumes of Swedish iron exports to the UK lasted from the mid-seventeenth century until the abolition of slavery in 1833—a crucial moment, which, as Nian’s archival research shows, the iron handlers opposed because it had a negative impact on their commerce. Against this backdrop, the video Trying to find a needle in the hay (2021), in which the artist indefatigably dredges a pile of straw, reflects the urgent need for other archives and new forms of art-making. As the black noise punctuates my art critic’s supposed objectivity, the slow molecular digestion of leftover raw materials within the aquariums suggests a rhythmic, recirculating timeline, whose beats gradually decompose the infrastructure of neglect. Listen closely to the bumping rails the next time you travel by train.

Frida Sandström is a writer, critic, and a contributing editor at Paletten Art Journal (SE). She is a PhD fellow in Modern Culture at the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Copenhagen (DK), where she is currently working on her PhD thesis, “Art criticism as social critique.”

[1] https://www.regeringen.se/informationsmaterial/2009/09/public-access-to-information-and-secrecy-act/.

DERNIERS ARTICLES PUBLIÉS

More Editorial