Since the end of last year the Fowler Museum in LA holds a comprehensive retrospective of the influential Cuban artist Belkis Ayón’s work. It was the first one in the US, since her work had been declared a patrimony by the Cuban government.

Belkis Ayón, La consagración II (The Consecration II), 1991. Collograph. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate. Courtesy of Fowler Museum

It’s only right that the venue for the first US solo retrospective on Belkis Ayón would be held in Los Angeles. Ayón was met with warmth and acceptance there since one of her very first US shows at the Couturier Gallery.

As I walked into the large gallery space at the Fowler Museum, I was immediately taken by the extravagant monochromatic palette of Belkis Ayón. There was little foot traffic that day, and ample time to be absorbed by the stories her work tells. The recurring blacks, greys and whites dance off the white walls in the room. Almost silhouette-like, the imagery is intense and on first gaze, often hard to access.

.

Belkis Ayón, Sin título (Sikán con chivo) (Untitled (Sikán with Goat)), 1993. Collograph. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate. Courtesy of Fowler Museum

.

Belkis Ayón Manso was born in Cuba in 1967. She used the printing processes of collography and lithography to build a platform of ideas. She printed on paper and used cardboard and other hard surfaces as the foundation of her prints, erasing the stereotypical notions of softness in women’s art practice. These cardboard matrices are the basis of the prints and she would assemble them to create large scale haunting canvases, almost memorializing the subjects within.

There is an unavoidable gaze of the subjects, their mouthless faces, silently watchful. It’s apparent that she is painting herself in these works. A quiet, silenced self, looking out onto the world, trapped in multiple tableaux.

The overlaying and repetitive nature of her process reflects the ritualism of the secret spiritual sect she sought to depict. She scored, cut and manipulated cardboard and paper and printed by hand, adding other dimensions of complexity through this labor-intensive process.

She became enamoured with the patrilineal culture of Abakuá and though a lot has been made of the delineation of that secret society in her work, to me it is a metaphor for a much more delicate discourse. It feels as though Ayón is using Abakuá as a reflection on the state of freedom of expression for the artist in 1990’s post-Soviet Cuba. The downfall of the Eastern Bloc would have caused turmoil in Cuba, the largest of the Caribbean islands, and expectations that Cuba would follow. Though artists were publicly funded, this lead to restrictions on their voices and subject matter. Through Abakuá, Ayón determined that these systems of patriarchy were dying and that the feminine, through the image of princess Sikán, would overcome death and torment to create a pathway that would lead to freedom of expression for the artist.

In the video ‘Siempre Vuelvo’ we see Ayón’s hands covered in ink, aligning herself with her work, immersing herself into the work. This mirrors her idea of the feminizing of the Abakuá myths by placing the woman centrally. The syncretism she creates by combining the Nigerian influenced Abakuá traditions with Christian tropes – the last supper, the fish, the snake – are emblematic of the cross-cultural paradigm she was navigating.

Throughout the work she is rewriting the story of Sikán one of the chief protagonists in the Abakuá imaginary. For Ayón it is the patrilineal secret system of Abakuá and the relinquishing of princess Sikán, from the mythological sharing of a forbidden secret to then becoming the sacrifice from where she ushers forth as reborn. The death of Sikán, not unlike the deaths of those in Judeo-Christian belief systems, underlines the rebirth of the princess in Ayón’s work. It is her body that we seek in the large scale prints, her gaze, her prayerful presence. Ayón herself said that Sikán was a representation of her – ‘the observer, the mediator, the tale-teller’.

.

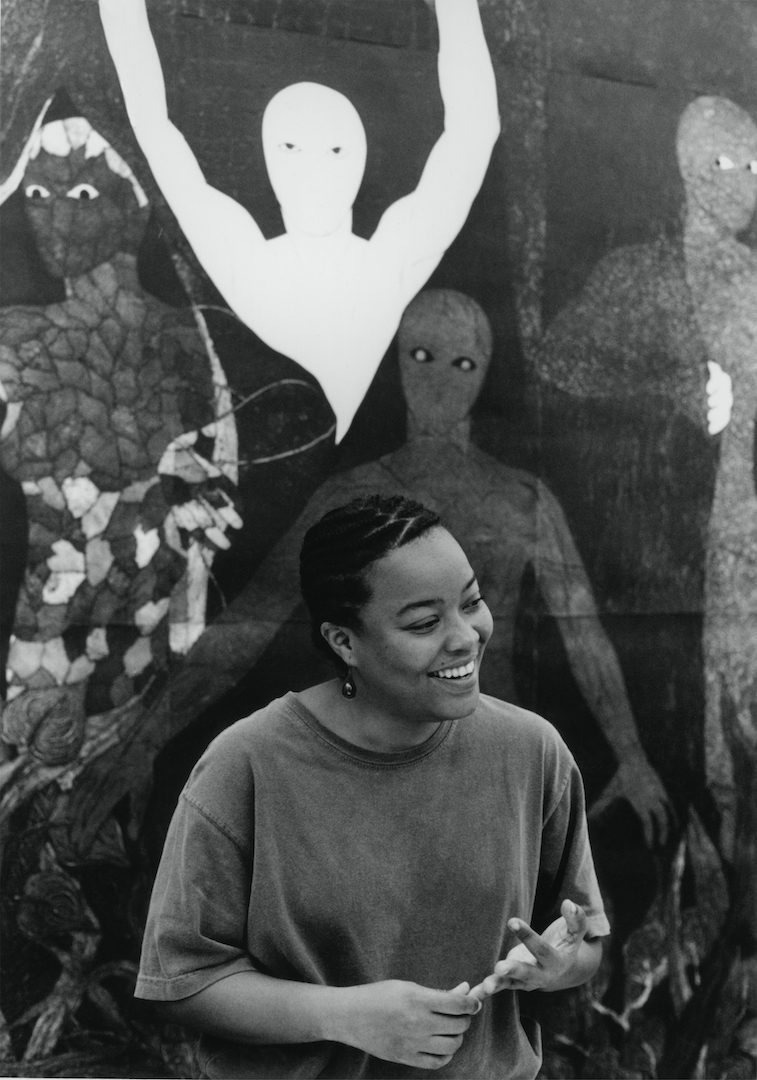

Belkis at the Havana Galerie, Zúrich, August 23, 1999. Photo by © Werner Gadliger. Courtesy of Fowler Museum

.

The parallels between other Cuban artists, Ana Mendieta and Tania Bruguera are explicit. Though the latter two would be seen as more performance-based interdisciplinary artists, there are still parallels in their critique of Cuba and/or the male-dominated art world and the machismo of both US and Cuban cultures.

Mendieta also expounded the ritualism of Cuban culture in her use of blood and there are parallels in Ayón’s smearing of the ink – the tactility of the process and engagement in producing work that comes from the hand also could be seen as very performative.

The curator of the show at the Fowler Museum, Cristina Vives, has worked with Bruguera and has been a diligent supporter of Cuban artists here and abroad. Vives has curated a vivid display of Belkis Ayón’s career. Though short-lived, Belkis Ayón’s career was a lively one. She toured many countries with her giant print works and though she sadly took her own life at 32, she left a body of work that is remembered and nurtured by her sister Dr Katia Ayón at the Belkis Ayón Estate.

.

“Nkame” October 2, 2016-February 12, 2017, at the Fowler Museum, UCLA campus, Los Angeles

.

Nan Collymore is a writer and ponderer. Materiality and embodiment are central to her work. She writes, programs art events and makes brass ornaments in Berkeley California. Born in London, she has lived stateside since 2006

More Editorial