Our contributing author Dagara Dakin interviewed the young prizewinner. She explained to us some aspects of her vision of a curator's practice.

Eva Barois De Caevel Photo: Étienne Dobenesque

In February 2014, C& interviewed the curator Eva Barois De Caevel about her event program “Who Said It Was Simple.”The program was held from January to March 2014 at Raw Material Company in Dakar. It was the first installment of a four-part series called “Personal Liberties” and focused in part on how “difference, minority and margins with an emphasis on sexuality” are treated in the African media.

On November 17 2014, during the annual benefit and auction of Independent Curators International (ICI), Eva Barois De Caevel was presented with the 2014 Gerrit Lansing Independent Vision Curatorial Award. This biannual award recognizes the work of an emerging international curator who has demonstrated great potential. Our contributing author Dagara Dakin interviewed the young prizewinner. She explained to us some aspects of her vision of a curator’s practice.

Eva Barois De Caevel

Photo: David X Prutting, Billy Farrell Agency.

Dagara Dakin: You recently received the 2014 Gerrit Lansing Independent Vision Curatorial Award. What are your impressions of the award’s significance?

Eva Barois De Caevel: The recognition was a wonderful surprise! As I said at the award ceremony, my curatorial practice is young, very experimental, political, and not necessarily seductive, so it was really difficult for me to predict how it would come across in the limited confines of the portfolio that I submitted to the judges. But Nancy Spector, who was responsible for making the selection, described the critical merits of my work using the word “unflinching,” which is of course an amazing source of encouragement. At the same time, the prize means recognition on an international scale, which dovetails with my desire to work in a range of geographies, one reason being my project’s thematic content. Also, I received it from an organization, ICI (Independent Curators International), that I was especially excited to start collaborating with. So this prize is a starting point for a number of projects, a way to have a conversation with important players about many ideas that I would like to realize in the years to come.

D.D.: I have the feeling that every curator develops their own idea of their position. In your view, what is the curator’s role? What’s your attitude about the task in general?

E.B.D.C.: Yes, clearly [we all see it differently]. And that’s great! It’s hard to answer your question because I’m specifically avoiding narrowing myself down to a rigid definition of the curator’s role. It’s not an easy thing. You are often accused of thinking you’re the artist or that you’re the researcher, and people would rather hear you venture a vague definition of your role than try to understand how hard you work to interrogate the curator’s function, to adapt it to the fields that you feel need investigating, and to adjust to the practice of the artists you work with. I believe that the curator’s role can be very broad. It is unfair to restrict it to set categories or quibble over creative authorship. For example, it’s possible that in future exhibitions I might produce or commission objects myself if I consider them necessary alongside the artwork, archives, and text. In my mind, curators’ role is to create new exhibition paradigms and to provide critical and theoretical accompaniment to the artwork that fits the specific geographical and political realities of the show and responds to major artistic trends.

D.D.: You are one of the co-founders of the curators’ collective Cartel de Kunst. Is that a way for you to launch your career in the field without feeling “alone against everything” or is there a different logic behind it? How is working with the collective different from working independently?

E.B.D.C.: Cartel de Kunst is an association that we created when we were still students completing our master’s program in 2011–2012 on “Contemporary Art and Exhibition” at the Sorbonne in Paris. We essentially saw it as a way to be young curators even though we were leaving the university setting to begin our professional lives, which we expected to be a tough transition. But, the ten members of the collective come from very different backgrounds and many of them have already had significant professional experiences. If you ask me, this collective is more than just a professional network, it’s an essential network of solidarity and friendship. I’ve always maintained a positive attitude as opposed to the general professional cynicism and the sense of being used that weighs down interns and young professionals. Starting the collective was a way of giving ourselves a role, giving ourselves power.

To respond to your second question, I’d say that working collectively is indeed different. Not different from working independently, since we are an independent collective (meaning that we are not permanently attached to an institution or organization), but different from work that I do on my own. My work with Cartel de Kunst does not consist of reflecting on the theoretical and critical fields that pervade the work I do in my own name, because – and this is specific to our collective – our activities are always focused on idea of teamwork itself. So everyone’s individual interests flourish elsewhere, even though I do also discuss my personal projects with the other members of the Cartel. But work in the collective flourishes on another level. Each of the three shows we’ve put on so far (one per year since we were established) has embodied a different perspective on the group and different ideas about the nature of curation. Besides, the group compels us to keep questioning ourselves, to keep moving forward. The group is all about discussion. There aren’t officially specified roles within the Cartel, so everything is in motion. Every decision is agreed on by the whole group. Sure, that translates into dozens of emails and meetings, but it’s exciting!

D.D.: You are also assistant curator at Raw Material Company in Dakar. Can you tell us about your work in that context?

E.B.D.C.: After I’d spent several months collaborating long-distance with Koyo Kouoh, Raw’s director and founder, followed by a six-month residency there until March 2014, Koyo invited me to become assistant curator. In practical terms, I am still based in Paris, but I am involved with the center’s activities from afar. My role consists of continuing projects that Raw initiated during my residency. For example, I’m currently working on putting together a publication that will document the entire “Personal Liberties” series, including my exhibit “Who Said It Was Simple,” but I’m also collaborating with Koyo on international projects. We’re currently preparing for an exhibition in Brussels called “Body Talk,” which will open in February 2015 at WIELS, and another exhibition “Streamlines” that will open in November 2015 at the Deichtorhallen. My relationship with Raw Material Company is a kind of collaborative effort. I share a lot with the space and with Koyo. It’s a relationship that has been extremely productive and helpful in my early career as a curator.

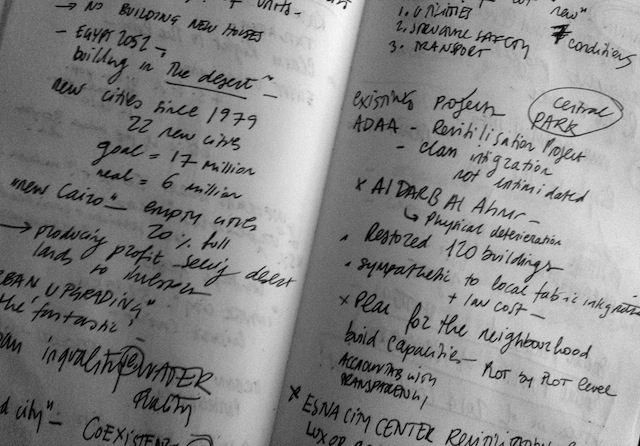

Adelita Husni-Bey, research notes, Cairo, June 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

D.D.: You seem very interested in the issues of negotiation that are currently being discussed in the revival of non-Western societies. And you invite artists, especially from Africa, to create, in your words, “work that examine closely our concepts of always, new, here, and there [in order to] create, to creolize – if I may borrow Glissant’s use of the term – new structures that stand against destructive traditionalism and against every form of imperialism.” Have you ever encountered exhibits that respond to that call? If so, can you give us a few examples? And finally, wouldn’t it be fair to say that, to some extent, your interests lie in zones of tension, areas where things are happening and assertive decisions are being made?

E.B.D.C.: Yes, of course. Because my work isn’t about tackling theoretical realities through art. My research takes as starting points the works of art and my interests in socially engaged practices, in fresh or refreshed creative devices in contemporary art film, but also in all other mediums when they borrow from historical, anthropological, or sociological methods, and when they are aware of being living objects in a post-colonial world. I think that these practices and their dissemination and contextualization by curators are truly essential for a revival of non-Western societies. I believe that that quest is embodied by the work of artists such as Kader Attia, Adelita Husni-Bey, Mark Boulos, Bouchra Khalili, Kapwani Kiwanga, Jelili Atiku, or Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, and I could mention many others. I’m very drawn to the idea that we are evolving in a globally post-colonial world and that this is the world that must condition our reading of every specific field of inquiry. Topics like gender, feminism, or sexuality should be considered in that context. Morality and aesthetics should be considered in that context. Consequently, it is natural to be interested in societies, events, or themes that are particularly marked by that context. So I wouldn’t say that I’m interested in zones of tension per se, but that the post-colonial reading of the world that inhabits all of my work leads me to highlight tensions and to work alongside artists and researchers with similar interests to contemplate those tensions, to give them shape, and to respond to them.

Mark Boulos, All That Is Solid Melts into Air (2008), installation view, 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art. Courtesy of the artist.

More Editorial