As the Dakar Biennale is coming up this year in May, C& presents its little series introducing young talent, exhibitions, cultural producers and their projects in Dakar.

Qui a dit que c'était simple / Who said it was simple. © Antoine Tempé. Courtesy: Raw Material Company

C&: Although you are still young, you have worked in several different art fields and engaged with different media in different places, in Dakar as well as in Paris. Could you begin by telling us about your background?

Eva Barois de Caevel: I was in a humanities program at university. After taking preparatory classes in literature, I specialized in aesthetic philosophy and art history for my Bachelor’s at the Sorbonne, followed by a maîtrise in contemporary art history, for which I looked at the role of video in contemporary art, the influence of film, and experimental film. Finally, I completed a Master’s in “Contemporary Art and its Exhibition,” which is a degree program in curatorial practices, also at the Sorbonne. After that I worked in the production of artists’ films. Now I’m starting out as an independent curator, whether in the context of the collective I belong to (Cartel de Kunst) or in the context of a residence, like the one I’m on now at the Raw Material Company, which ends in March.

C&: How did the exhibition cycle Libertés individuelles come about?

EBDC: When Koyo Kouoh started the Raw Material Company, one of her primary objectives was to create a place that was not devoted to contemporary art alone, but rather a space where art functions as a medium for social or political questions. Koyo imagined Raw as an intersection of culture, theory, art, and political and social questions. That is why she had long wanted to work on a cycle about the notion of personal liberty. Her aim was to look at this subject through the lens of her reflection on particular current events, especially in relation to her experience in Senegal and her view of the media. For Koyo, no subject is taboo for culture and she felt that Raw, as a place of culture, could permit itself to address the question of sexual practices between people of the same sex in Africa. She wanted the project to take the time to examine the question in depth, without urgency, and in a sufficiently exhaustive way for the discussion to be carried out calmly and constructively. Libertés individuelles was thus devised as a year-long program, constructed around different acts.

C&: You’re talking about homosexuality, but there is no mention of this word in the project description.

EBDC: Yes, that’s intentional, since I am in fact not talking about “homosexuality.” I am careful to avoid this term precisely because it is imported. I did a lot of thinking in preparing for this exhibition, and I came to the conclusion that using a Western term is a mistake and only promotes tensions. The omnipresence of a Western-centric discourse and nomenclature is a problem. In Senegal, for example, the Wolof language has a whole vocabulary for sexual acts between women or sexual acts between men, as well as very subtle nuances to describe practices or attitudes, but there is no precise term for “lesbian” or “gay.” Vocabulary is also a space that needs to be decolonized, a space subjected to imperialism. One has to be vigilant.

C&: So Qui a dit que c’était simple / Who Said It Was Simple is the title of the exhibition…

EBDC: The title is taken from a poem by Audre Lorde. I like this poem a lot. It tries to describe a woman’s anger and asks whether identity is necessary or not and about an individual’s independence in relation to their practices. What possibilities are there for defining oneself? Audre Lorde’s reflections were a motivation to me during my research. The phrase itself is amusing; it was a good way to start off the cycle, as a response to everyone who was horrified by this project, dubious, or completely against it.

.

Qui a dit que c’était simple / Who Said It Was Simple. © Antoine Tempé. Courtesy: Raw Material Company

.

C&: Can you tell us something about the situation in Senegal, the political context?

EBDC: The political sphere is very much in thrall to the religious sphere, and the latter uses the topic of sexual relations between people of the same sex as a campaign argument, in order to scare people and rally them around certain ideas. As a result, the image the media disseminates about the Senegalese perspective on this issue has its source in the fantasies of the religious: it is the notion of an imported disease which supposedly never before existed in Senegal. Paradoxically, this kind of discourse is reinforced by the NGOs and the defenders of human rights who promote a homosexuality that in fact has nothing Senegalese about it.

C&: You started by consulting the archives?

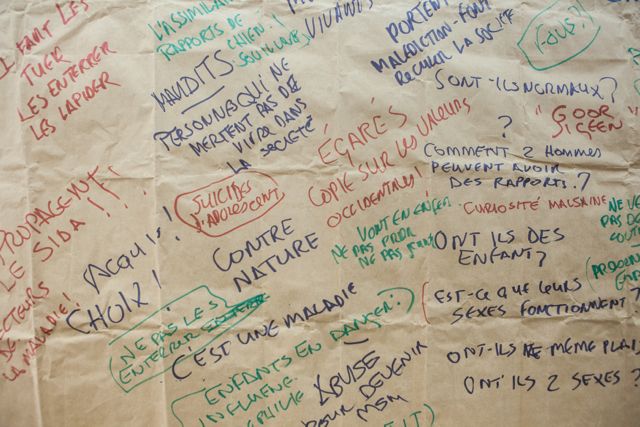

EBDC: Yes, I began by researching in media archives, an ideal resource for putting together a portrait of the collective imaginary of today’s Senegal and of what society’s opinion is according to those who steer it. We did research in the press archives at CESTI, the journalism school, concentrating on the last ten years. CESTI provided us with more than 2,500 press articles. I selected about a hundred that seemed representative, allowing me to draw up a meaningful chronology of these last ten years. The exhibition presents this timeline, which spans the period between 2003 and 2013. I invite the visitors to take measure of the growing presence of this topic in the media and to note what events are the focus of the years with a particular glut of related articles. One can see the political and religious instrumentalization of the issue during certain periods when there is something at stake politically. The motivations of the journalists also become apparent: the commercial side of their treatment, given that this is a story that sells, but also the demagogic and populist manipulation of their work, in particular by certain religious groups. I supplemented the timeline with archival magazines, radio programs, blogs, websites, and political cartoons.

Qui a dit que c’était simple / Who said it was simple. © Antoine Tempé. Courtesy: Raw Material Company

C&: Did you go further in your historical research into the archives?

EBDC: I was interested in going back much further in time, which meant working not only with media archives but also with researchers, historians, and anthropologists. There are a number of African researchers who have conducted historical studies of the sexual practices between people of the same sex in Africa. Concerning Senegal, I worked with Professor Cheikh Ibrahima Niang from Cheikh Anta Diop University, a major specialist who has extensive knowledge on the subject and has amassed a wealth of documentation in the course of his research. Two of his articles presented in the exhibition address the integration of men who have sexual relations with other men in the history of Senegalese society. Niang examines the political role of these environments, specifically the place inhabited by these men in relation to women, in precolonial society. His work reveals the existence of a sophisticated and peaceful social structure that found ways to harmoniously integrate the phenomenon.

C&: Why did this change?

EBDC: There are of course different points of view on that question. I can mention a few directions the answer can take, however. For many African researchers, Ifi Amadiume for instance, one of the primary factors leading to the discreditation of these sociocultural practices and structures was colonization, which called into question the ways in which education and the transmission of knowledge worked. Prior to colonization, knowledge had been fluid, passed down from generation to generation according to an age-set system that is truly Pan-African. But then this was disrupted and completely undermined, its continuity broken. Religious discourse—missionary and otherwise—accompanied this process. Personally I put a lot of stock in this idea of a colonial origin: the entire set of cultural practices came to be misunderstood, mocked, and fell into disuse because the West arrived with all its self-confident assumptions about knowledge, about the transmission of knowledge, about what is right, what is appropriate, what is permissible. When everything is destroyed, what’s left behind is a shambles: the ignorance with which we are confronted today and the adherence to (or the importation of) an imperialist model for regulating this type of question. But the rejection of this model is not a source of re-creation either.

C&: How is the Libertés individuelles program structured? Your exhibition kicked off the cycle…

EBDC: That’s right. Two other exhibitions will follow. The first week during the Dak’art biennale, curated by Koyo Kouoh and Ato Malinda. It will be made up of works by contemporary artists such as Kader Attia, Zanele Muholi, Jim Chuchu, Andrew Esiebo, and Amanda Kerdahi—African or African Diaspora artists. Ato Malinda’s project is to think about the existence of a homosexual identity in Africa, about the possibility of a queer identity that is properly African. Does such a thing exist in Africa and can it exist in Africa? If so, how? Where does it exist, if it already does? Where might it emerge? Jim Chuchu’s work, for example, presents us with hybrid figures that are inspired both by African pagan traditions as well as the contemporary imaginary of homosexual practices. Finally, the third component of the exhibition cycle, curated by Gabi Ngcobo, is conceived as a process, that is, the exhibition will take shape as a function of the exchanges and interactions Gabi intends to facilitate between individuals here in Dakar and researchers from around the world concerning this same topic of African queerness. The final act of the exhibition will be a publication.

C&: What is your view of the role of art as a militant activity? What are your thoughts on militant art?

EBDC: Fortunately art does not occupy a predefined space when it engages with particular topics; it is not rigid. Many of the exhibition’s visitors, incidentally, are bothered by this. They want me to choose a preset position on the subject: that of an activist, an advocate, a politician, a defender of human rights, etc. But it is not about any of these positions; I am a curator, and I am very lucky to be able to work in a place whose philosophy embraces the idea that one can extract theoretical reflection from this vast notion of art and exhibit it as such, all the while having as one’s primary vocation the exhibition of works of art. But to respond more directly to your question, yes, I believe, not in militant art per se, but in what is called socially engaged artistic practices, and I believe in the role of the curator in these types of processes. I also believe that the postcolonial questions that concern me can be addressed by artists. And, finally, I believe that the field of globalized contemporary art needs to be decolonized.

Qui a dit que c’était simple / Who Said It Was Simple, 29 January–29 March 2014, Raw Material Company, Dakar.

Seminar: Reporting on Difference. Different Report? Media, Difference, and Marginality, 7–9 March 2014, Raw Material Company, Dakar:

“Reporting on Difference. Different Report?” is a three-day seminar that addresses the generally discriminating radical tone with regards to sexual difference in African news media. The seminar will bring together social scientists, historians, religious leaders, lawyers, editors-in-chief and journalists to discuss the current situation in multiple working sessions.

Eva Barois de Caevel has a degree in contemporary art history from Paris-Sorbonne University. Her current interests surround postcolonial questions in contemporary art as well as socially engaged artistic practices. Together with her collective, Cartel de Kunst, she co-curated the exhibitions Temps étrangers (Mains d’Œuvres, Saint-Ouen, 2012) and The Floating Admiral (presented as part of the Nouvelles vagues series at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013).

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

More Editorial