The artist talks about making art that is hard to decipher and the importance of portraying Blackness.

Contemporary And: In the past few years, I’ve found that it has become more and more established to create portraits with varied facial expressions. Especially for Black faces, partly to counteract the dehumanization of Black people. So I find it very interesting that your figures do not have facial expressions. Why is that?

Ruth Ige: Growing up in a space where there were a few Black people was extremely hard. People had ignorant stereotypes of Africans and Black people. It was hard to meet people for the first time, because they would feel like they knew who I was based on their negative perceptions of my skin color and nationality. Plus, there was this hyper-awareness that would occur, because many had not seen a Black person before. That caused a lot of unpleasant interactions and still does.

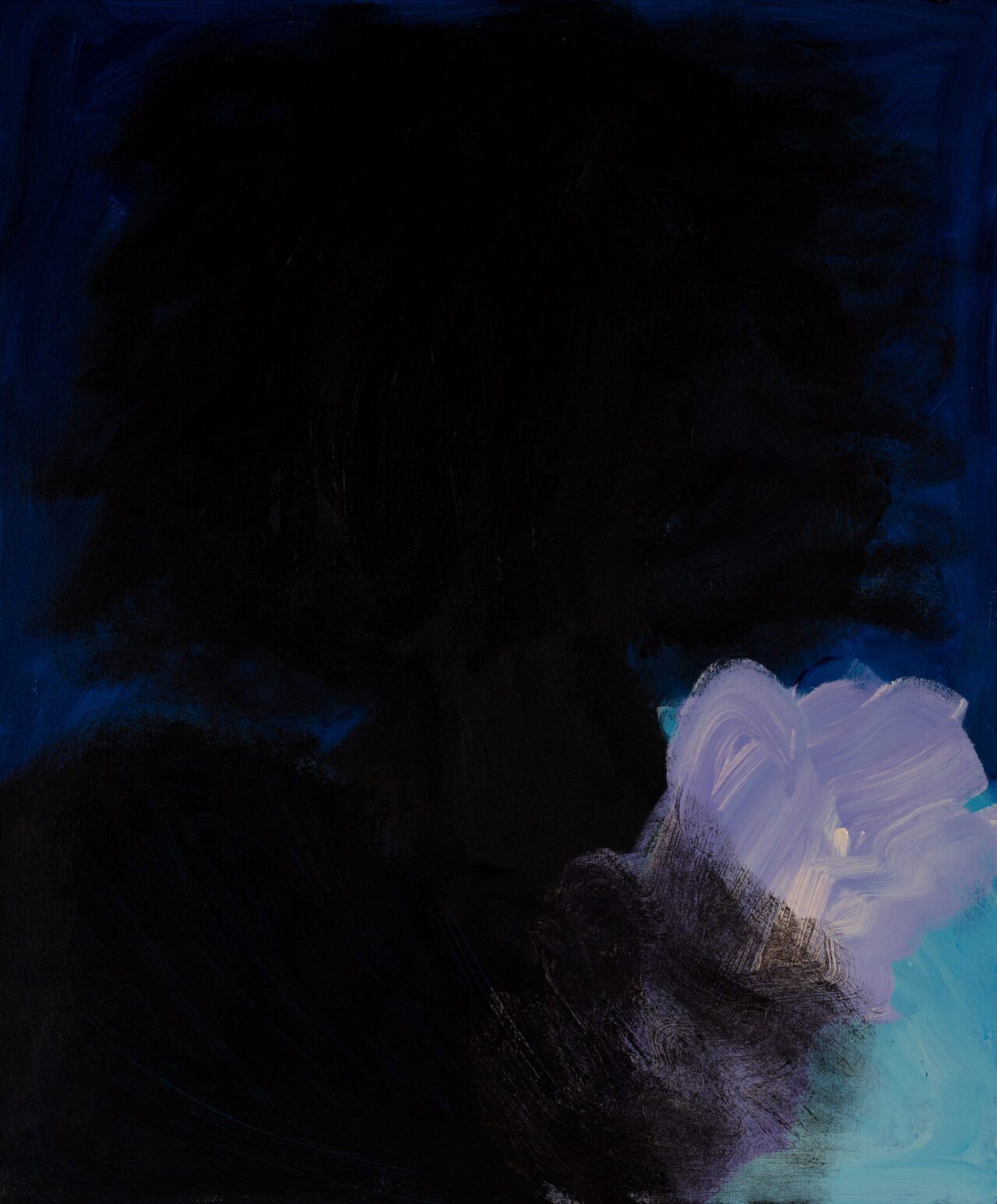

As much as I tried to change that perception or provide the truth of who I was as an African Black woman, they were fixated on their negative preconceived notions of me. It could not be changed. It was traumatic and frustrating for me and still is today. I decided to omit the features, because I wanted to show people that you cannot understand all. Humans are complex and it might take years to fully understand someone. I am removing that certainty people try to search for when viewing something. This is important in relation to the topic of blackness. Blackness to me is beautiful, complex, and multi-layered, but society sees it as static.

I describe what I am doing as a constant revealing and concealing process, instead of just a veiling. The viewer is left wandering who these figures really are. Their facial features are not accessible, but their Blackness is very present. I wanted to show empowerment, but also a form of privacy.

I do not see it as dehumanization, but a form of protection. I am almost giving them control over their personhood. We as humans constantly reveal and conceal things about ourselves as we navigate space. I am just doing this through paint while centering the Black experience. Art is a form of empowerment for me as a Black woman. I am a shy person, and my art gives me the courage to speak about things that are important to me. Through art I have found my voice.

But it is also important to me that I do not participate in anything that could be dehumanizing to how blackness is portrayed. I know abstracting the figure can be tricky territory, especially with my topic. Everything has been birthed through years of thorough research and conversations with me and others.

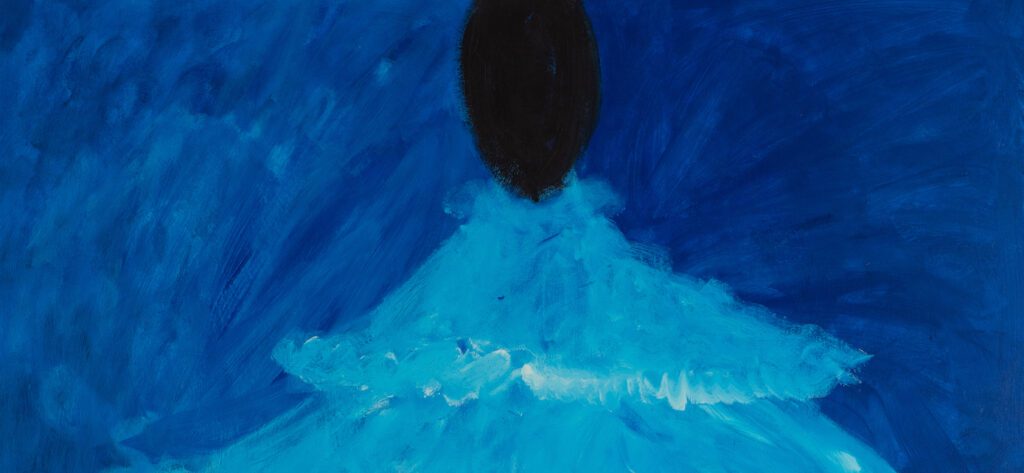

C&: Your palette tends to be quite minimalistic, and blue is very present in your paintings. What does the color represent or express for you, that other colors don’t?

RI: Blue stands out to me above the others because there is a multiplicity. The color has a depth that is almost spiritual. It is otherworldly, but also ordinary. It can convey sadness, but also new beginnings and wonder. It has multiple dualities that I find quite intriguing. With blue I can create a certain atmosphere or frequency. In my work, creating a meditative, calm, or quiet moment is immensely important. Blue allows me to create a slowing down and drawing in. Blue is also culturally important to the Yoruba people of Nigeria. I am Yoruba and Igbo. In Nigeria we have an indigo fabric called adire by the Yoruba people. All these things tie into why I use blue. I also genuinely love it. I find it a very healing color.

C&: I read that you are “interested in creating images that are not easily understood.” What additional value do you see in abstraction?

RI: I originally began as an abstract painter, without the figure. I have always loved abstraction and its visual language. In art school I began to feel that just focusing on the material aspect of abstraction was not enough for me personally. I decided to add the figure and this coincided with my growing research around Blackness in relation to art history and documentation. I would say that abstraction is the language that helps to translate the figure. It is the tool I use to create slippages between the familiar and otherworldly and the figure and its environment. Through abstraction I can conceal and reveal aspects of the figure. I can create images that are hard to decipher or place.

Black artists have an immense role in founding figurative art, but many people do not know that Black artists had a hand in the birth of abstraction as well. For me it is important to embody both figuration and abstraction, but abstraction is the lens I view the figure through and that is quite valuable to me.

C&: What do you want to express through your artwork and what is your goal in portraying Blackness in your art? And what does Blackness mean to you personally – is it something you can define?

RI: For me, Blackness is expansive. Racist systems, colonization and the media have convinced a lot of people that Blackness is restrictive. This is one of the biggest lies that has been indoctrinated into our society. We as artists usually come across individuals who tell us that doing work about Blackness or race is restricting our art. They try to convince us that our art is not art anymore, because there is Blackness attached to it.

I think such comments say a lot and could be further unpacked. It is a form of gaslighting and it can be hard. However, I am someone who has always questioned systems of thought. Blackness is not restrictive to me. I feel that I might not be able to fully reach its depths in this lifetime, but I am enjoying discovering all that it holds.

In my art I hope to show that Blackness is expansive. I hope to challenge how society perceives Blackness. My painting employs aspects of speculative fiction – my recent body of work, Freedom’s Recurring Dream, is a good example. Society has a tough time viewing Blackness in future spaces and imagined realities. We have seen extreme backlash to the inclusion of Black characters in productions like The Flash, The Little Mermaid, Star Wars, Obi Wan Kenobi, and most recently The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. The extreme hatred around Blackness being part of these spaces is very telling about how Blackness is perceived.

In my work I hope to show areas of Blackness that are intrinsic to the Black community but have somehow been deemed as not by racist systems.

C&: Why did you choose to study and live in New Zealand? Is there a special art community you were interested in?

RI: I moved to New Zealand from Botswana when I was eleven years old, because my parents always wanted to move here. I grew up in New Zealand. There are amazing POC artists that I have had the pleasure of meeting and working with here in New Zealand.

Jody Adwoa Pinkrah is a student of anthropology and expanded museum studies. She is interested in visual arts, music, and black lives in global contexts.

OVER THE RADAR

A multilayered experience of Immy Mali's Letters to my Childhood presented in six chapters.

More Editorial