Writer Vusumzi Nkomo highlights the solo exhibition The Other Side of Now by Tuan Andrew Nguyen, on view at Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, South Africa. This exhibition presents films, sculptures, tapestry, and archival family photographs. Engaging with the transnational complexities left in the wake of colonial violence, it addresses the quieter narratives within Vietnamese, Senegalese, and Moroccan histories. While the exhibition has some weaknesses, it fosters a space for collective reflection and historical reclamation.

Installation views, 'The Other Side of Now’, courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA. Photograph by Dillon Marsh.

History is not real. It may feel like it is, but in fact it is a logical culmination of careful discursive practices and maneuvers. That is to say, we make it up. At the heart of his solo exhibition at Zeitz MOCAA, the Vietnamese American artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen is concerned with our retrospective relationship with the process we call history, especially its fictive properties as a collectively engineered ensemble of stories and divergent narratives.

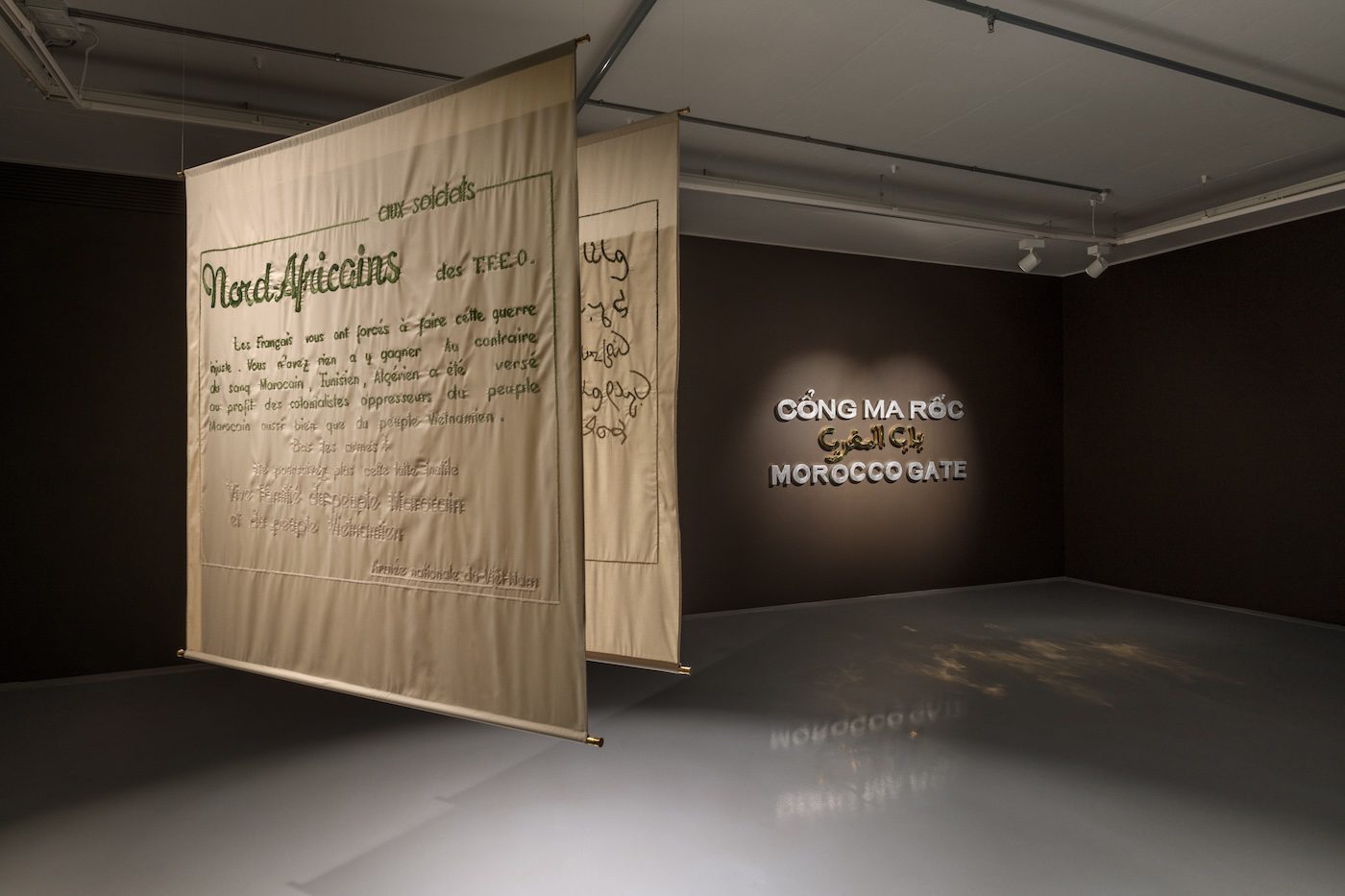

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, Letters From The Other Side (2024). Installation views, ‘The Other Side of Now’, courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA. Photograph by Dillon Marsh.

Three films take up most of the exhibition and shoulder its ethical, political, and emotional claims. Elsewhere the sculptures, such as Singing Bowls (2022) and Ricochet (2024), made from salvaged bomb metal and brass artillery shells, are both mobile and participatory. They demonstrate a consistent logic of engagement, whereby they draw in the viewer through the undisciplined nature of play, motion, and sound. However, the tapestry Letters From the Other Side (2024) and the wall-based text sculpture titled Contact (02) (2024), while sustaining the technical precision characteristic of Nguyen’s practice, are perhaps the least imaginative works because they rely on literal translations of historical and cultural artefacts: the tapestry lifts words from a propaganda leaflet and the wall text takes its words from a monument in Vietnam.

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon (2022). Installation views, ‘The Other Side of Now’, courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA. Photograph by Dillon Marsh.

In the films, Nguyen demonstrates an impeccable fidelity to the principle that fiction is constitutive of history and memory work. Here, fact, often cinematically closer to the grammar of documentary-as-evidence, loses ground and coherence and begins to give in to a kind of speculative logic, the very stuff of cinema. In The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon (2022), a single channel video, Nguyet (played by Nguyen Kim Oanh) is an artist who lives and works in Quang Tri (Vietnam) and cares for her mother (played by Truong Thuong Huyen). Both women are navigating the aftermath of post-war Vietnam and the death of a father and husband killed by unexploded ordnance (UXO). Nguyet is frustrated by her encounters and perceptions of the objects she works with, whether she’s buying or selling them. Following a consultation with her aunt, she discovers that she is the reincarnation of Alexander Calder, the late American artist most famous for his kinetic sculptures.

Installation views, ‘The Other Side of Now’, courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA. Photograph by Dillon Marsh.

Though I find reincarnation as a narrative device to be productive as long as it troubles and unsettles the modern subject’s investment in the linear unfolding of time, I would like to bring up these questions here: What are the implications and risks (political and otherwise) of mapping the life of a Vietnamese woman (that is, Nguyet) and a survivor of empire’s world-breaking war machine, unto a white US-American man inside the belly of empire (that is, Calder)? What is gained by this comparative, analogizing gesture? Who gains what from it? Is the intended gain the emotional engagement of an international non-Vietnamese and western audience in the film’s diegetic demands? For me, what exactly is gained by centering a white US-American in this story remains unclear.

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, 2019. 4-channel video installation, 2k, 7.1 surround sound, 28 minutes. Film still. © Tuan Andrew Nguyen 2024. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

In The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019), which traces and dramatizes the legacy of the Anti-French Resistance War (1946–54) and the West Africans, a Senegalese in this case, who were coerced into fighting for the French colonizers, we are confronted with the stain of trauma and its transference as the primary and raw inheritance of the formerly colonized. The exhibition’s curatorial statement refers to “Vietnamese and Senegalese solidarity,” but neither the artist nor the museum broach the tensions around Blackness in Vietnam – what Frantz Fanon, in Black Skin, White Masks (1952), calls “Negro-phobogenesis,” the ways in which Blackness, and perhaps anti-Blackness, constitutes “a stimulus to anxiety” or a sort of irrational phobia. Rather, the contradictions pertaining to the global structure of anti-Blackness and solidarity, including in Vietnam, are flattened out. This should have been a crucial issue in staging this exhibition in this part of the African continent, and will be crucial in its reception by a (South) African audience.

Installation views, ‘The Other Side of Now’, courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA. Photograph by Dillon Marsh.

The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon counts among its breathtaking moments a long shot of an exploded bomb used as a raised garden bed with flowers blossoming on top, and a close high-angle shot of a prosthetic leg lying next to a mirror showing its phantom reflection. The former exposes the brutality of imperial war and its exerting demands on the environment, the ensuing ecological degradation, the relationship between violence and nature, or, crudely, the nature of violence. The latter lays bare the industrial scale by which statecraft exposes the expendables of the global majority to biopolitical harm and risk. The toll of the pain of the phantom limb doubles as we are shown both the actual physical pain of losing a part of the body and the traumatic psychic residue that outlives the actual moment of violence and operates beyond representation in language. Nguyet’s attempts to buy and sell these objects she works with (such as the bombs) evince (1) how grief is shared, exchanged, and traded, (2) how healing rubs against the demands of the money-form within our capitalist social order and mode of production, and (3) how war, the (global) circuits of racial domination, and the fascist necropolitical death-machine reproduce and intersect. As Nguyet puts it, “I make a living by selling these dead things.” To refuse to remember is to be complicit in the entanglement of these global forces with local histories.

Installation views, ‘The Other Side of Now’, courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA. Photograph by Dillon Marsh.

Considering Nguyen’s concerns with the afterlife of airborne violence in the context of “the American War” in Vietnam (as the artist put it during the press preview), it is curious that he provides no aerial scanning of the landscape in any of the films presented, including Because No One Living Will Listen / Người Sống Chẳng Ai Nghe (2023). What results is a reading of and access to the landscape primarily from the human-eye level. Everything and everyone appears close and immediate, and, most crucially, the violence that produced this context in the first place is not cinematically reproduced. Moreover, the curatorial decision to make it impossible for all the screens to appear in their totality within the viewer’s field of vision creates a generative context whereby they may only be intuited by the viewer as fragments, although the acoustic cacophony undermines this curatorial structure. Just like our retroactive reconstruction of history, the past always appears fragmented from the critical standpoint of the present.

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, Because No One Living Will Listen / Người Sống Chẳng Ai Nghe, 2023. Two channel, 4K video, stereo,10 min. Film still. © Tuan Andrew Nguyen 2024. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

Triggered by our bodily vibrations and air, the movement of Nguyen’s (or Nguyet’s?) Calder-esque sculptures as other viewers’ faces appear in their reflective surfaces suggests that the only permissible stance is to consider how you are always already implicated relative to your own structural position within the crisis and catastrophe that constitute our neoliberal present and onto-epistemological order. The stakes are obviously lower on this museum floor than in the landscape inhabited by subjects who must live under permanent threat of unexploded US-American bombs.

The Other Side of Now by Tuan Andrew Nguyen, is on view at Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, South Africa until 20 July 2025.

Vusumzi Nkomo is a writer and educator based in Cape Town.

More Editorial