Fondation H is dedicating its first exhibition to an icon of the Malagasy art scene: Madame Zo. Here, Hemerson Andrianetrazafy reflects on her work.

“[Integrating objects in my works] is how I express myself. It is how I communicate through my art. You can find these materials anywhere, and not pay attention to them. They find a new life, a new strength within my [creations].” Madame Zo

A major figure of the Malagasy artistic world, Razakaratrimo Zoarinivo, better known as Madame Zo, showed her presence through her discretion. With her jolly face and friendly smile, she was one of those people who never raise their voices. Wherever she went, she quietly exuded her status as a respectable, and respected, Grande Dame. Wherever she went, she managed to assert herself by the sheer force of her artistic production. Highly sensitive, she was nonetheless always up to crossing the limes (1) of aesthetic convention in order to create works that she herself described as “Adala be” (“insane”). From one exhibition to the next, these never ceased to amaze, challenge and/or destabilize the public (2), who hardly expect to be completely uprooted, in a world where fibres flirt with matter in a knowingly random space, and with exceedingly unexpected combinations.

Madame Zo was the worthy heiress of the weaving tradition strongly rooted in Malagasy culture (3). Before international trade scaled up in the 18th and 19th centuries, did Malagasy women not themselves attend to all local needs for fabrics and basketry? Multi-millennial practices that have enabled them to master the entire process of handcrafted weaving still exist today, such as silkworm breeding, or cotton planting. The daily tasks of framing and spinning are still pursued, the mastery of which was once transmitted from mother to daughter, from generation to generation. Loom components are never far from women’s spaces. Indeed, it used to be a well-known fact that no woman could marry without knowing how to take care of all family needs in fabrics and basketry. Despite receiving technical training in her early thirties, Madame Zo made weaving her passion, eventually launching her art and textile business in 1990. Already then, she had a burning desire to walk off the beaten track and move towards borderless creativity. Above all, she had found the need to share what she had to offer as part of her artistic sensibility.

In 1997, she became a weaving teacher herself at the Espace Métier Solidarité Firaisankina (4). Selected at the Biennial of Contemporary African Art, Dak’Art 2000, she presented at the Salon international du design africain et de la créativité her textile work Armature fibre de verre, a tape of movie film woven into a cotton thread warp, which was supported by a tent frame. This major work already expressed the direction she had chosen: integrating/combining/diverting and above all, repurposing everyday objects.

From then on, she no longer stuck to materials dedicated to weaving, such as silk, cotton, sisal, and synthetic fibres (5). Choosing an experimental route, she strove to integrate any object into her works that had caught her attention. Thus, from one creation to the next, she gradually shifted her perspective of our environment littered with all sorts of materials. One thing leading to another, she managed to go beyond use values and focus solely on what she deemed essential: to consider any existing thing as a thread to be wefted.

“Anything can be repurposed, she would say. It is only through lack of imagination that we throw away objects we no longer use.” (6)

Is it about dismantling objects to structure another reality? Or reinterpreting existing things to unveil other meanings? Her approach is, above all, playful. Like those little girls who play outside telling stories by knocking pebbles together (7), she dissects her universe, generates forms that grow increasingly bolder with the integration of unusual elements. As she creates, she never ceases to allude playfully to this modernity with its multifaceted industrial products, in stark contrast to her meticulous handcrafting process. But even more significantly, her favorite thing was to reuse plants and agricultural products: leeks, dead leaves, blades of grass and other green leaves were inserted or even used as weft for fabrics. And these mediums are so familiar that they are likely to interest everyone.

Said Madame Zo: “There was always someone to (…) take an interest in my weavings. Peasants, craftspeople, manual workers like me! At a vegetable market, I showed them that leeks could be used for things other than food…” (8)

In fact, her approach was well suited to the Malagasy perspective according to which no being, thing or fact can be exempt from meaning (tsy misy dikany, tsy misy fotony). It is not uncommon for her creations to be used as bases for endless debates. Quite often, questions arise by themselves, in order to dissect the creator’s “design”, especially when its constituent elements can be identified within the local network of understanding. For example, five ears of corn woven into a network of fibres [Fig.1]. Spatial composition seems accidental, born out of chance… However, the wide spacing of three ears of corn and the tight grouping of two others echo a visual and symbolic combination of the even and the odd, the complementarity of the ego and the other, an introduction to their essential Unity and Diversity, a reference to the five fingers of the grasping hand, and so on.

Is weaving, the ultimate reference of social interaction, not in itself meaningful? The fibres, whether silk, jute, or cotton, refer to the fundamentals of togetherness. They can combine, unite, and get entwined to generate the communal dimension, and other, more solid, substantial, realities in the shape of rope or fabrics. Weaving as a sublimated figure of fihavanana establishes the template defining the normality which is to be built. Kinship, solidarity, and harmony can then form a common ground by spreading lengthways along the warp threads, and widthways along the weft. The harmonious combination of each element in the whole will thus form a fabric where everyone can find their place. In this sense, Madame Zo did make effective use of her art not only as self-construction but also as a support for togetherness. And her strength was never to force her own interpretation on anyone, always allowing the public to discover it themselves or wander around the maze of their own imagination.

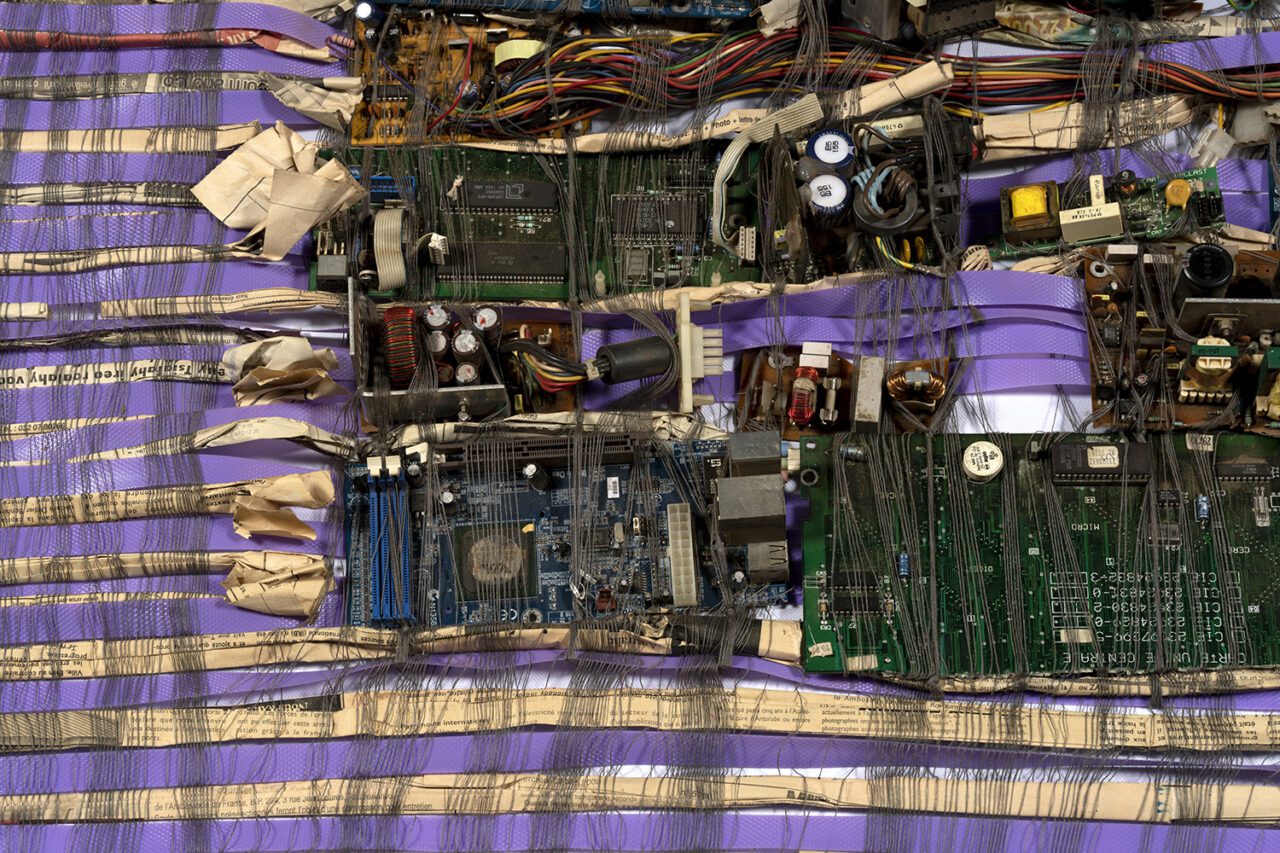

Through her polysemic works, Madame Zo has opened the door to all possible interpretations. But this was not just about meaning or significance, it was also about a formal approach exploiting all occurrences to offer the best visual expressions. At times by showing creases or breaks in the weft, and at others by playing with contrasts through opposing textures. Against the unassuming hues of natural fibres, and the softness of cotton threads, she highlights the cold glimmer of cellu- loid tapes, the slender lines of leeks, the earthy hues of withered leaves. Does she not sometimes invite us to lose ourselves in the tangle of ropes with chrome bicycle parts contrasting with the matt tint of sisal threads and the gleaming shine of metallic components? [Fig.2]. When she uses gray threads, wood shavings and magnetic tapes, her constant preoccupation is spatial balance and aesthetic significance. These actually combine harmoniously to tame and / or disconcert our eye.

Said she: “I don’t assemble the materials to necessarily convey a mes- sage, I just find this collusion between materials more poetic.” (9)

Throughout her experiments, Madame Zo built a world apart. A universe which took after her. She fashioned herself an expressiveness feeding both on her internal needs and outer solicitations. Making weaving her main practice, she slipped into a current of contemporary art moving away from past aesthetic and museum conventions – Arte Povera, Art de la Récup – a current eager to get in tune with a material culture related to the consumer society. Towards the end, after much reluctance to qualify her approach in any way, she eventually defined herself as an artist committed to the art of eco-recycling (10).

In July 2020, too soon, this cultured woman left us. She was open-minded and always up to date on the great debates fueling the art world of her time. She shaped her own references to modulate her creativity according to her needs and her sensitivity. Above all, she played a full part in the Malagasy contemporary art movement, which, at the dawn of the third millennium, reflected upon the relationship between artistic expression and the constraints of the here and now (11).

Hemerson Andrianetrazafy is an artist and historian. His text was initially published in the official exhibition catalogue, December 2023.

Madame Zo, Bientôt je vous tisse tous [Soon I’ll weave you all], still on view through 29th of Feburary at Fondation H in Antananarivo, Madagascar.

1 The term limes carries the meaning of ‘limit’ or ‘border,’ formerly used to refer to the barrier defending the Roman Empire.

2 We had the honor of spending time with her when we did group exhibitions together in 2006 (Mahasinga, Singularité, Singularity) and in 2011– 2012 (TransPorter Lambahoany).

3 The weaving production is currently used to supply the market in lambamena (silk shrouds).

4 Dak’Art 2000, Biennial of Contemporary African Art. Catalogue pp. 76 and 130.

5 “Bamboo leaves, rice straw, magnetic tapes… everything to her is creative material. Madame Zo weaves strange connections between bold interior design and contemporary art”.

6 “Introducing herself as an artist weaver, Madame Zo does not solely weave textile fibres. Plant, animal, mineral materials, ‘anything can be used’, she believes, ‘even old telephone cards, pens or inner tubes that she incorporates into silk or cotton!’” Joro Andrianasolo, « Madame Zo : matières à créer », No Comment, 1er juillet 2013.

7 Tamaboha or Tantara (stories): A game played by Malagasy little girls, who tell each other stories using pebbles as characters, often knocking them against each other as they come up with elaborate scenarios.

8 FB post by Madame Zo, 13th December 2019.

9 Posted on her FB page on 28th May.

10 Self-introduction on her Facebook page Zo-Artiss.

11 She consistently took part in the lengthy discussions which the Association VAIKA (Association pour l’Instauration et la Promotion de la Culture de Demain) organized regularly during various Annual Contemporary Art Fairs between 2000 and 2015 in Antananarivo.

FEMALE PIONEERS

More Editorial