Gauthier Lesturgie takes a closer look at the complex work of Angolan artist

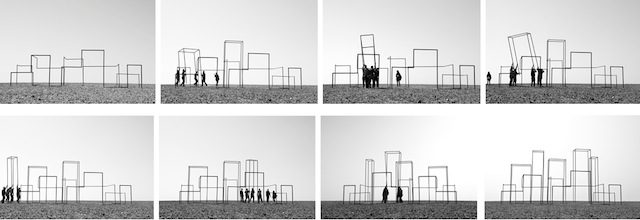

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Compacted Distance, 2014 (Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation). Courtesy of Galeria Filomena Soares

“The steel buildings tower above us like a giant skeleton so enigmatic that one wonders whether the city ever truly existed or whether this was nothing but a raving poet’s description of a mirage in his struggle to survive in the desert.” (1)

The discovery of a sign in the Namib desert bearing the inscription “Miragen” led Kiluanji Kia Henda to contemplate the symbolisms and representations of the city. The image of Dubai has become the go-to embodiment of the “ideal city,” the “urban mirage” with a futuristic appeal. It is a qualified architectural utopia, albeit one regularly put down, and its ongoing status as a spectacular role model has turned it into a prestigious formula copied by many countries. In this show, Kiluanji Kia Henda identifies the consequences of this for his native city of Luanda.

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Settings for an imaginary landscape I, 2009. Courtesy of Galeria Filomena Soares

The artist divides his time between Lisbon and the Angolan capital, giving his discourse an irony facilitated by that critical distance from his geographical subject, which is sometimes Luanda but often tied into a larger context through his use of fiction.

In 2004, the architectural theorist Yasser Elsheshtawy coined the term “Dubaization,” which has since caught on and been frequently applied to describe the act of building a city that is inspired by spectacular effects but irreverent towards its surrounding context. Essentially Dubai has become a spectacular model of “success” for export.

From the outside, the grandiose skyline with its surreal tower the Burj Khalifa (the tallest man-made structure in the world), literally implanted in the flat desert landscape, is a physical embodiment of the concept of “tabula rasa” that allowed for its construction. With the “fertile nothingness of the desert” as a canvas, anything could be imagined and anything brought to life (2).

In his series of photographs of sculptures, The Building Series, the artist mimics that visual dichotomy in the Maleha desert of the Sharjah Emirate by installing fine metal rods that form a collection of geometrical solids suggesting the skeletons of various buildings. With these gestures towards architectural shapes, more symbolic than functional, the artist creates a link to the sona tradition from northern Angola. The practice of creating a lusona (3) is a technique of drawing on sand with one’s finger while telling a story. Without interruption, the storytellers trace a precise pattern of lines and dots that symbolically illustrate the narrative they are recounting. By basing his sculpture/architecture on these sand drawings, Henda establishes direct relationships between storytelling, urbanism, and urban representations.

With Paradise Metalic (2014), the artist took his use of story a step further. The piece is a quadriptych video fairy tale that ventures into absurd, almost burlesque, territory and draws on a number of edgy cinematographic techniques including autonomous sound; repeated gestures, and nearly absent dialogue. We follow a sleeper’s dream, his hallucination about his ideal city, and encounter different structures created by Henda.

In the artist’s native Angola, the question of the city’s future is crucial and topical, particularly in reference to the capital Luanda, where an extensive urban reconstruction plan is now underway. The campaign of urban “renewal” there aspires to secure the title of “world city” that has been bestowed on Dubai. A text written by the artist in 2010 describes the capital of Angola, which didn’t obtain independence until 1975, becoming a vacant space afterwards and anxiously awaiting its new tenants (4). This period was immediately followed by a civil war lasting 40 years. These circumstances froze the country’s economy for decades resulting in an unprecedented rural exodus. The artist is not explicitly returning to that past, but it is necessary background in order to understand contemporary transformations. After the return to a modicum of stability, the rise of oil and diamond wealth allowed the country to develop its economy at a breakneck pace. China’s 2004 offer of large loans gave the Angola government ambitions of pursuing projects on a pharaonic scale: architecture and urbanization in the service of reclaiming prestige.

In 2011, the Angola government unveiled Kilamba City, a housing development intended for 160,000 inhabitants and built at great cost 20 km south of Luanda. The city remains a ghost town. As the artist writes, “The city emerges from a dreamlike dimension and its costly ornamentation makes it into a fantastic decorative object. Your ideal of happiness is perverted when the primal function of providing shelter proves to be ineffective.” The city was sterile.”

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Rusty Mirage (The City Skyline), 2013. Courtesy of Galeria Filomena Soares

The revealing process of “Dubai syndrome,” which situates urban politics as a race to prestige at the expense of necessities. The artist derisively re-envisioned these maneuvers with his installation Instructions to Create Your Personal Dubai at Home (2013), providing an assortment of how-to guides for creating symbols of the city using household supplies: DIY ski slopes, palm islands, and even skyscrapers.

In response to the government’s aspirations, Henda presents a humorous vision of “his” city, built by and with the inhabitants rather than according to pre-established structures. The work conveys an “organic” and hybrid vision of economic and urban processes that the new urban architects attempt to conceal behind flamboyant facades. His use of metaphors and absurd procedures is quickly overshadowed by the brutal reality behind them, particularly exemplified by the three passages on the wall. Using fierce yet poetic language, the artist denounces the construction of a new artificial oasis superimposed upon the city, an image made for a postcard but hollow underneath.

Kiluanji Kia Henda, “A city called mirage,” 18 Sep–29 Nov 2014, Galeria Filomena Soares, Lisbon

(1) Excerpt from a Portuguese text hung on one of the exhibition walls.

(2) Fadi Shayya, “Speculations and Questions on Dubaization,” The State, 2013.

(3) Singular of sona.

(4) Kiluanji Kia Henda, “Niemeyer’s Dream and the parallel universe,” buala.org, 2010.

Gauthier Lesturgie is an independent art writer and curator based in Berlin. Since 2010 he has worked within several structures and projects such as the Galerie Art&Essai (Rennes), Den Frie Centre for Contemporary Art (Copenhagen) or SAVVY Contemporary (Berlin).

More Editorial