In the 1970s Congo (then Zaire) went through a cultural rejuvenation supported by the then autocratic leader Mobutu. This kind of patronage turned out to be double-edged sword whereby a burgeoning cultural scene developed under a spell of propaganda. As The Democratic Republic of Congo prepares for a new beginning with the recently elected Felix Tshisekedi, our author Costa Tshinzam looks at what we can learn from Mobutu’s errors.

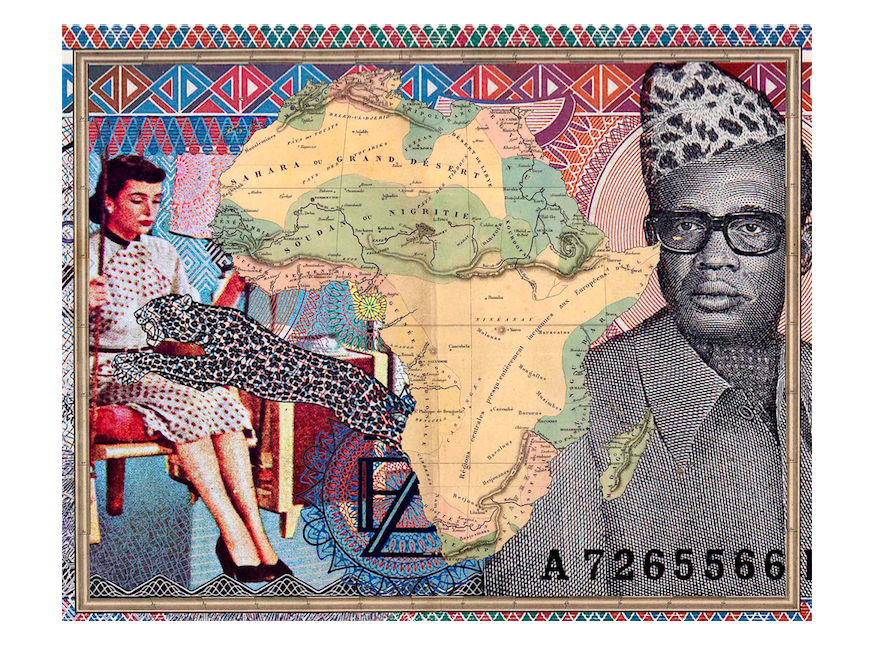

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1838, Atlas Elémentaire, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

In Mobutu’s Zaire (1965-1997), now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the approach to politics claimed to be “authentic.” It set out to return to a sense of African legitimacy by making a clean break with everything that evoked Western control. President Joseph Désiré Mobutu himself became Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga. One story even relates that Vincent Yves Mudimbe, one of the country’s leading intellectuals, drew on the first letters of the names of his students “Vumbi” and “Yoka” in order to retain the initials “V. Y.” in his signature. In terms of clothing, the abacost (abbreviation for the French “à bas le costume” – literally “down with the suit”) was promoted. This collarless jacket, cut in a light fabric, generally with short sleeves, very quickly became the symbol of the ruling elite, who rejected the tie, which was considered a sign of being Mundele Ndombe or “white black.” But what importance did this policy have for the practices of visual artists in Zaire after the disruptions caused by the colonial power and its way of exploiting culture as a propaganda tool and instrument of control? How would Zaireans experience this change in the realm of art?

Mobutu’s liking for art would have grown out of his membership of an obscure association in Belgium devoted to the promotion and protection of art, which brought together a number of Zairean students. His presidency went on to be characterized by a strong sense of patronage. It was Mobutu who issued the manifesto of the Popular Movement of the Revolution (MPR) at N’Sele in 1967 and the resolution of the first ordinary session of the MPR in 1972.[1] His “generous” patronage was underpinned by these two key texts. Among other things, the manifesto states the following. “Artists, writers, and philosophers should be encouraged by the State, which will guarantee the international propagation of the most remarkable works and figures in the field. The art schools and organizations will receive funding.” This idea is supported by the national institutions, who, moreover, consider this period to be the “Golden Age of Zairean art.”

Art and the artist were rehabilitated in the Mobutu era. The presidency of the Republic of Zaire and the president’s family were focal points in the purchase of modern Zairean works of visual art. Pieces by the artists N’damvu, Mantento, Baku, and Lufwa decorated the presidential residence: this was a first for Zairean art, which found its place within the national community.

The Mobutu Sese Seko Fund was set up alongside the Fund for Cultural Promotion (FPC), which subsidized cultural projects by taxing advertising. The former granted a social allowance to Zairean artists of advanced years or afflicted with illness. The National Association of Zairean Artists in Visual Arts (ANAZAP) was set up to harmonize, represent, and defend the interests of the artists.

Apart from Zaire 74, a music festival organized on the fringes of the Rumble in the Jungle, which pitted Muhammad Ali against George Foreman in 1974, the country successfully organized a conference of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) in 1973 and the International Congress of Africanists in 1978.

Those who view our art history through an international prism do not see this golden age in the same way: Belgian art critic Roger-Pierre Turine makes no mention of the Mobutu period in his Les Arts du Congo: D’hier à nos jours (La Renaissance du Livre, 2007). More recently the exhibition event staged by French gallerist André Magnin completely skips this period in Beauté Congo – 1926–2015 – Congo Kitoko (Fondation Cartier, 2015).

Is it not an inevitable conclusion that the erasure of this glorious period recorded under the Mobutu era was encouraged by the about-face taken by his principal champions, who took a critical view of him at the end of the Sovereign National Conference (CNS)?

Museologist and art critic Badi-Banga Ne-Mwine, who once praised Mobutu to the skies—going so far as to describe him as a “crucible of the authentic Zairean artistic character, patron of the arts, author of the promotion and influential standing of Zaire’s artistic culture”[2]—performed a volte-face when, in an allusion to President Mobutu’s cultural policy, he spoke “getting out of the cultural disaster,”[3] his words backed by all the power of the rostrum at the CNS. On the same platform, journalist Charles Tumba Kekwo drove the point home by accusing the powers that be of having “neglected the creation and promotion of cultural spaces across the nation, thus bringing about the cultural undernourishment of our people.”[4] He excoriated the fact that the cultural activities of Zaireans could in large part be practiced on “foreign soil,” that is to say in the embassies and cultural centers established by foreign countries in Zaire.

In view of the above, it is clear that President Mobutu understood that a great nation only develops by promoting its identity, that this identity is best expressed through art because it makes a mark on the history of a people, and that a people without history is a people without soul! This had a positive impact until the point when politics got the upper hand over his sense of patronage and culture began to be used as a tool, to alienate his people. Tumba Kekwo concludes by saying, “Culture has never been a central concern of our governments, despite the slogans and absurd expenses occasioned by the process of organizing sessions of collective hysteria and the cult of personality, erroneously called ‘festivals of cultural life.’”

Today Congo (Kinshasa) is experiencing a crucial period in its history. In addition to a new president promising a renewal of public policies, a new assembly is welcoming fresh faces, including a number of artists, such as musicians Jean Goubald and Lexxus Legal, and theatermakers Ados Ndombasi and Vital Nsunzu. From this perspective, rethinking “good intentions” and the errors of Mobutu’s cultural policy allows us to envisage the future as a realm in which art is not merely an instrument of propaganda but a space for renewing the imagination of a people who have been able to demonstrate their desire to remain united in their diversity.

Costa Tshinzam is a writer, blogger, and author who is a member of the Habari RDC community. He took part in the C& critical writing workshop generously funded by the Ford Foundation in Lubumbashi, where he lives and works.

[1] “The Ordinary Session of the Popular Movement of the Revolution . . . tasks the Executive Council with pursuing efforts to develop culture in areas such as music, literature, theater, cinema, fine arts, etc. with a view to ensuring their standing both nationally and internationally; and to base Zairean culture on a process that consistently turns to authenticity rooted in the heritage of traditional values, while accepting external cultural contributions.”

[2] Badi-Banga Ne-Mwine, Contribution à l’étude historique de l’art plastique zaïrois moderne (Kinshasa: Éditions Malayika, 1977.)

[3] Badi-Banga Ne-Mwine, “Sortir d’un sinistre culturel,” in Quelle politique culturelle pour la Troisième République du Zaïre?, ed. Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem (Kinshasa: Bibliothèque Nationale du Zaïre, 1992), 117.

[4] Charles Tumba Kekwo, “Guérir du kwashiorkor culturel,” in Nziem, Quelle politique culturelle pour la Troisième République au Zaïre?, 89.

More Editorial