In our latest series – Female Pioneers – we look at female artists from Africa who have made major contributions to art on the continent. This time we reflect on the work of Ghanaian photographer Felicia Abban. In the 1950s she started as her father’s apprentice in a seaside town in the Western Region of Ghana. She would, however, go on to become one of the continent’s most respected photo artists of her day – on the payroll of Kwame Nkrumah and a detailed analyst of her country’s transformation.

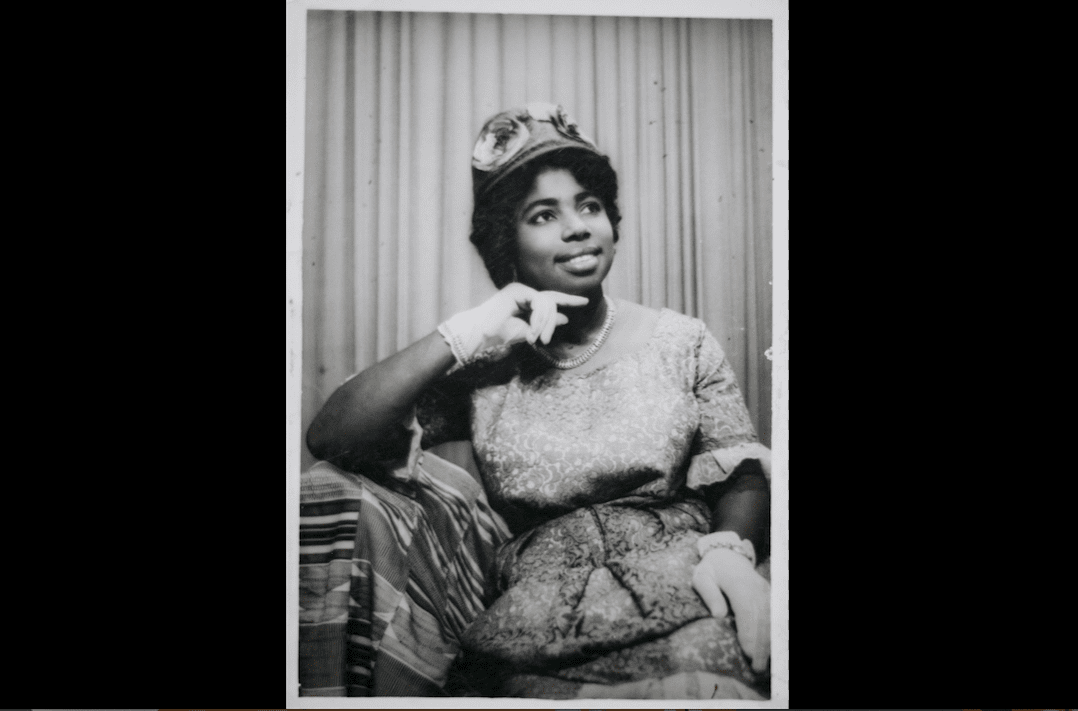

Felicia Abban. Self Portrait IV.

Here is a story:

There was once a man who lived in a small house, in a small neighborhood, with all his family and friends, and neighbors living in other small houses nearby. Every day he would walk through his neighborhood, along the small paths and short alleyways that separated one house’s clay walls from another’s, smoking his jot. When the children in the area saw him they would squeal: “Papa Puff Puff is coming! Papa Puff Puff is coming!” And he would respond by blowing billows of smoke – to their dismay and delight. One day he died. But because he loved his cigarettes so much, at his funeral his friends, family, and neighbors decided to place one jot in his mouth and another between the index and middle fingers of his right hand. They put him to rest in his most comfortable night clothes. A loved one leaving with his loved things.

****

It might be known that Felicia Ansah Abban frequented her father’s photography studio as a child growing up in Sekondi-Takoradi, in Ghana’s Western Region where she was born in 1935. The eldest of six children, Abban became her father’s apprentice at the age of 14 and spent the next four years working under his meticulous and methodological eye before leaving her hometown for Accra at 18 as a newly married young woman.1

Within a few months she opened “Mrs. Felicia Abban’s Day and Night Quality Art Studio” in Jamestown, Accra, then the center of town. It was situated close to other studios, including J.K. Bruce Vanderpuije’s “Deo Gratias” and James Barnor’s “Ever Young Studio”.

During her early career, Abban also worked as a stringer for the Guinea Press Limited – the publishing house of President Kwame Nkrumah’s Conventions People’s Party – but kept her studio practice close to her heart. Her career spanned sixty years until she eventually stopped working in 2013 due to arthritis.2

Abban is widely known for her studio portraitures, particularly her self-portraits made ahead of a night out or a political event; taken, she says, as a way to promote her business. Additionally, through her self-styling, acute awareness and participation in the fashion trends of the day, her self-portraits resembled images in fashion magazines, or, in an even more contemporary context, style feeds on today’s social media.

Less documented are Abban’s outdoor everyday images which, unlike her already set studio, required some staging. Like her contemporaries, she captured images of the country at a turning point. Take, for instance, the image of a baby, sitting stern-faced against a wax-print background held up by a third party – the person’s foot can be seen poking out at the corner of the sheet of fabric. A second image shows a woman having her portrait taken against another wax-print fabric, also revealing the appendages of the fabric holders – a leg, chest and arm on one side, a hand on the other.3 The outside finds its way in.

****

Here is another story:

At a funeral, a group of mourners listen to a life retold by an orator. Nearly all of them face him; a few look into unoccupied space, two look at the body. This moment is captured like a scene from a play. But the actors have their backs to us, the audience. They are not performing for us, it rather feels like a rehearsal.

Like the image of the child and the image of the woman described above, these photographs give an insight – though perhaps unintentionally – to what happens backstage, breaking down the fourth wall that seeks to portray an ideal scene, as can be seen in many of Abban’s self-styled studio portraits. Here, instead, we are reminded of the construction that takes place before the stage is set, the camera positioned and the shutter clicked.

Indeed, during her career Abban became the go-to touch-up artist for post-production services, with detailed precision adding color and accents here and there, in line with what was popular at the time. It is through this lens, in these moments of (post-)production between fantasy and reality, that I think of Felicia Abban’s studio portraits. In a realm where we can see that stories can be created and future lives can be imagined.

I think about Abban’s journey in this way: As a young woman from a seaside town trying to make her way in the cosmopolitan capital city. As a modern woman – in an industry dominated by men – cleverly positioning herself in soon-to-be-independent Ghana, working as a personal photographer to the president of the country for a number of years. And as one of the few women of her generation to be recognized in the field of photography, yet to have her contributions well-documented in scholarship.

Billie McTernan is a writer and editor. She is currently pursuing an MFA at the Department of Painting and Sculpture at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana.

1. Dr Laurian R. Bowles, “Dress Politics and Framing Self In Ghana: The Studio photographs of Felicia Abban” in African Arts Volume 49, Number 4, Winter 2016 (pp. 49)

2. Ibid (pp. 48)

3. These images were on display at an exhibition at the ANO institute in Accra, 2017.

The work of Felicia Abban will be part of the first Ghana Pavillion curated by Nana Oforiatta Ayim for the 58th Venice Biennale, taking place from 11 May to 24 November 2019.

FEMALE PIONEERS

More Editorial