A group exhibition curated by Meriem Berrada at Palais de la Porte Dorée raises important questions on epistemological violence in France

On a spring day on my way to the Eiffel Tower I bumped into a memorial for the Algerian War facing the river Seine and thought to myself – wow, progress. Upon reading the details, however, it became clear that the memorial is for the lives lost while fighting for French imperialism – rather than for the millions of Algerian lives lost on Algerian soil. The plaque made no allusion to what on earth was France doing fighting a war in Africa, or the lives of the Algerians massacred 4 kilometers down river, by Pont Saint-Michel, for protesting that war in 1961. A massacre in plain sight in the center of Paris, then largely censored by the state and the press in the country of liberté until 1998. It was orchestrated by the same civil servant who collaborated with the Nazis to deport more than 1600 Jews, yet who, in 1961, had been awarded the Legion of Honour by French President Charles de Gaulle.

This was the backdrop of my visit to one of the exhibitions of Africa2020 Season, the large-scale French event headed by N’Goné Fall that aims to address “the challenges that contemporary societies are tackling – about the past, the present, and mainly the future.”

Entitled Ce qui s’oublie et ce qui reste (What is forgotten and what remains), the exhibition is aptly housed in what is currently the National Museum of the History of Immigration (Palais de la Porte Dorée), east of Paris. The euphemistic name of the museum doesn’t quite do justice to what it is, what it shows, and what it does. Suffice here to mention its façade, built in the early twentieth century to house the international colonial exhibition (one of those exhibitions that featured human zoos): its reliefs represent French colonies through figures such as topless women in the Caribbean, accompanied by explanations of how those colonies served France (Martinique – sugar cane, Morocco – cereals).

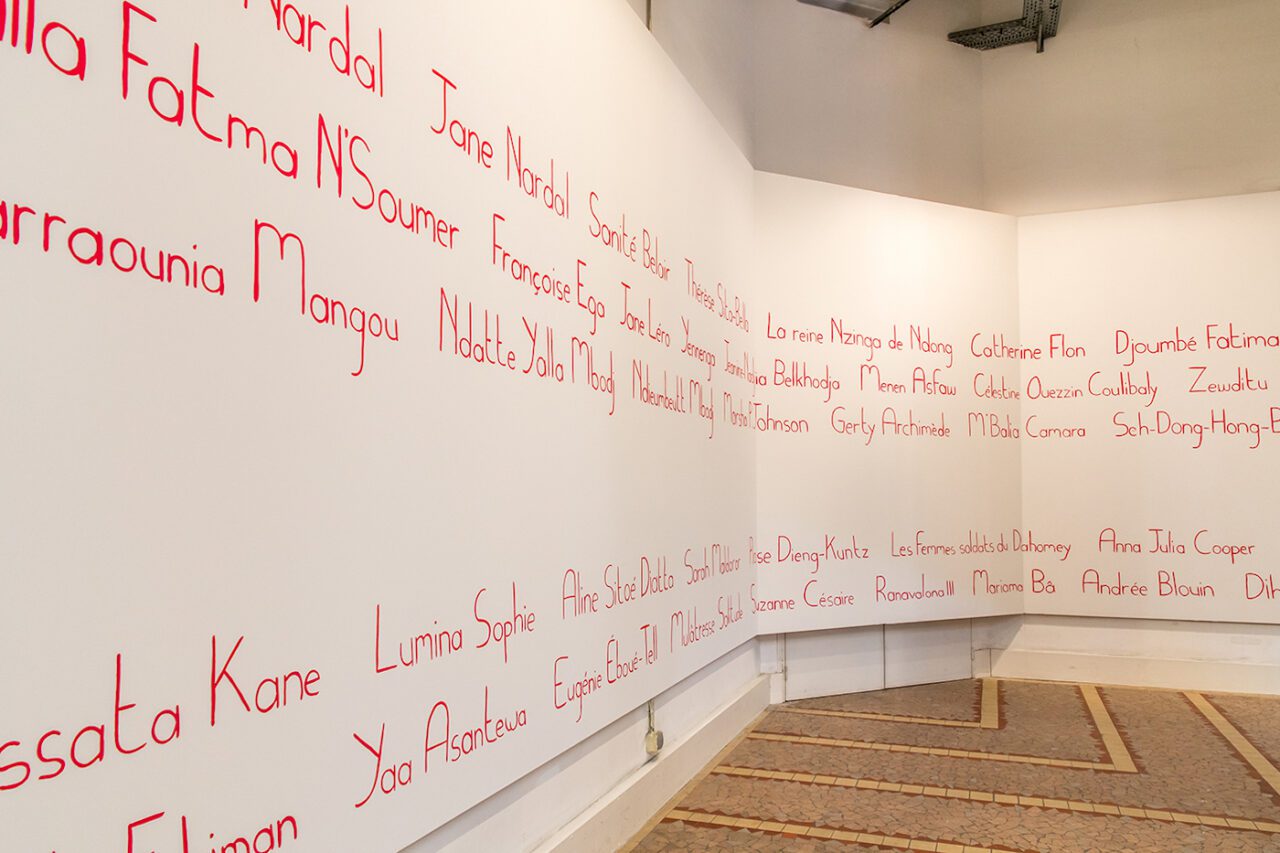

But nothing could have prepared me for what I saw inside the museum. Curated by Meriem Berrada of MACAAL, the exhibition occupies a space only accessible through a hall of frescoes of France’s colonial subjects in the most racist and sexualized depictions. Enslaved Africans on their knees raising their fettered wrists to a white priest, or maghrebi hijabis naked from the neck down – too horrifying to share photos of it here. The show itself brings together artists from across the continent who engage with ideas of memory, erasure, and transmission of culture. Several works engage directly with the building and raise important questions. In Seriti Se Lerato Shadi invites visitors to whitewash the names of women of color that are painted on a wall, pointing at our individual roles in reviving or wiping out history. Joël Andrianomearisoa’s fabrics dilute their surroundings into similarly toned abstractions, while Sammy Baloji’s memory series featuring colonial images of Congo raise questions about who has the right to use and capitalise on racist and sexualized colonial imagery, and why.

Yet the questions that seem to me most pertinent are the ones the building itself raises, and they are too many for a single exhibition to deal with. Why is it still there? How can such a symbol of French racism go from being the “Museum of the Colonies” to being the same thing under a new name? Why is there no acknowledgement of the violence of this building? Could this exhibition bring discourse in France into the twenty-first century?

The very name of the building speaks of a type of epistemological violence that still pervades French thinking. It conflates immigration with colonization when the two are in fact opposites, suggesting France was a benevolent colonizer and immigrants to France invaders. This same logic prompted Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Rally party, to compare France’s rising Muslim population to the Nazi occupation. There are plenty of people in France who are vocal about France’s ongoing colonialism and silencing, such as Rokhaya Diallo, Nadir Dendoune, Maboula Soumahoro, Dorothée Myriam Kellou, Houria Bouteldj, Nacira Guenif-Souilamas, and Histoires Crépues. Yet this has not resulted in structural change, and President Emmanuel Macron even insisted that France would not take down statues of controversial colonial-era figures amid the BLM protests last year. What can the arts do about this?

One prominent example was La Colonie , which was cofounded by artist Kader Attia in 2016 and closed its doors for lack of funds in 2020. La Colonie had the goal of challenging amnesic and harmful postures, particularly related to all the forms of denial that Western national narratives practice. In a podcast with e-flux, Attia recounted instances when white French men would interrupt talks at La Colonie to deny or justify colonial violence. This was accompanied by the institutional violence of neglecting the only place in the Parisian art scene that consistently harbored contemporary post-colonial criticism.

However, we’re no longer in the 1960s and in a globalized art world artists shouldn’t have to fear institutional reprisals, especially because many have careers that no longer depend on a single country. And in a digitized world, anti-colonial artistic gestures and actions that can’t happen physically in France can also happen online.

So can Africa2020 Season bring discourse in France into the twenty-first century? Some of it was already there, albeit suppressed – La Colonie being an example. And if one exhibition alone creates so much food for thought, what could potentially come out from all the others? The big challenges are keeping the conversation generative, and figuring out how the French artistic community can reimagine what respectable anti-colonial art can be.

Text by Will Furtado.

Special thanks to Themba Bhebhe.

A major event taking place in France entirely focused on African perspectives. Find interviews, installation views and the current program here.

More Editorial