An Exhibition that Welcomed Grief at the Door and Pulled out a Chair

26 June 2024

Magazine C&

Words Rosie Olang’ Odhiambo

8 min read

On a curatorial trip to Kampala, curator Rosie Olang’ Odhiambo shares her impressions in a letter to a loved one in Nairobi.

Darling,

May’s arrival seemed sudden. Had it really been two months since my trip to Kampala? Clocks and calendars feel out of sync with the rhythms of life. Inelastic. One deadline and another. An attempt at routine that I remained disobedient to. A heart dense and over-kneaded by grief, and on and on.

And yet it is now the start of June.

As I make my way through my endless to-do list, I am also finally making room to gather my thoughts and untangle what those three days in Kampala meant to me. Despair has been close, and so when I think back to early March, that brief and wondrous time away, I find myself in a different heart-space, re-enchanted. I am reminded that turning to each other and gathering is the medicine and bond that keeps us alive in real ways. A lived experience of the Gwendolyn Brooks sticker on your laptop:

we are each other’sharvest:we are each other’sbusiness:we are each other’smagnitude and bond.

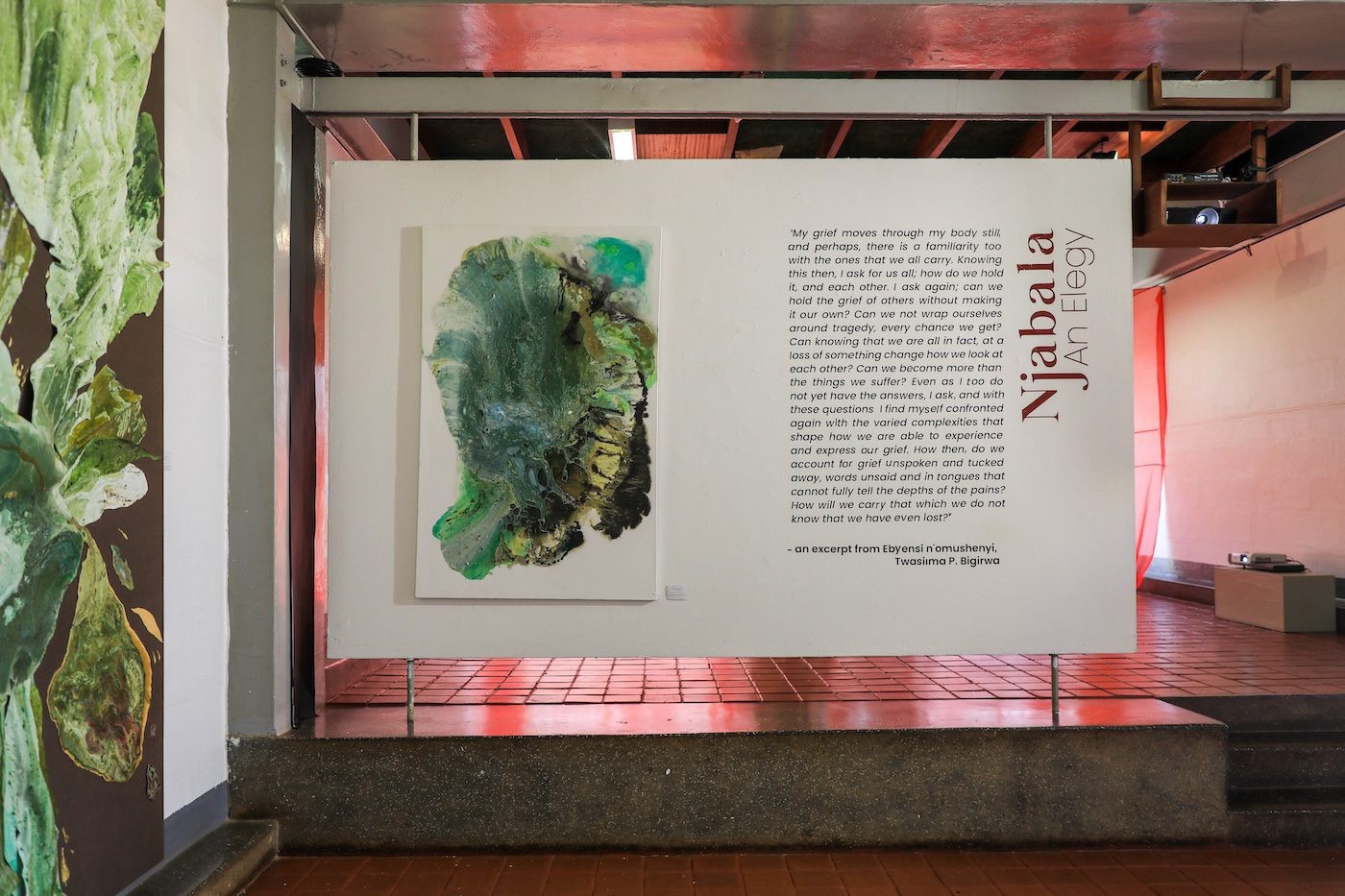

But woow, I am getting ahead of myself as I often do. I can’t quite remember how much or how little I told you about my reasons for travelling to Kampala, so forgive me if I repeat myself. I was attending a two-part gathering convened byNjabala Foundation andAWARE that featured the exhibition the Annual Njabala Exhibition, this year titled Njabala: An Elegy, and the symposium Tracing a Decade: Women artists of the 1960s in Africa. Both happenings were a balm over sore places.

Charity Atukunda, Joy and Sorrow, and Dreamscape: A meeting point, both 2024. Installation view at Njabala Foundation. Photo: Royal Kenogo.

Theexhibition featured six women artists, Charity Atukunda, Helena Uambembe, Letaru Dralega, Lerato Shadi, Liz Kobusinge, and Wambui Wamae Kamiru Collymore, as well as writer Twasiima Bigirwa, whose storytelling and working methods offered a generous experience of mirror (inwards) and window (outwards).

At the heart of Njabala: An Elegy, is the quote:

I do not want to tell you what happened, I want to tell you how it felt.

Every time I read this sentence I pause and read it again. (sometimes up to four times.)

This refrain by Zambian writer Namwali Serpell from The Furrows: An Elegy is the frame by which the curator, E.N. Mirembe, welcomed grief at the door, pulled out a chair, and invited us to sit in a room together. In the exhibition catalogue, they wrote:

It is difficult to pin a place on the map that does not hurt. We know the facts (death, everywhere), we know the numbers (unspeakable). How does it feel? (one must, here, listen to Michael Kiwanuka’s Solid Ground at least twice.)

I think about this last sentence, this invitation to a sonic soothing,and wonder how you have been tending to your grief(s). Where does it sit in your body now if you were to do a scan? What about it is new and surprising, and what is familiar? With whom are you in community at this time? Are you finding ways to sit with and also resist despair, ways to expand your lungs, your breath through it all?

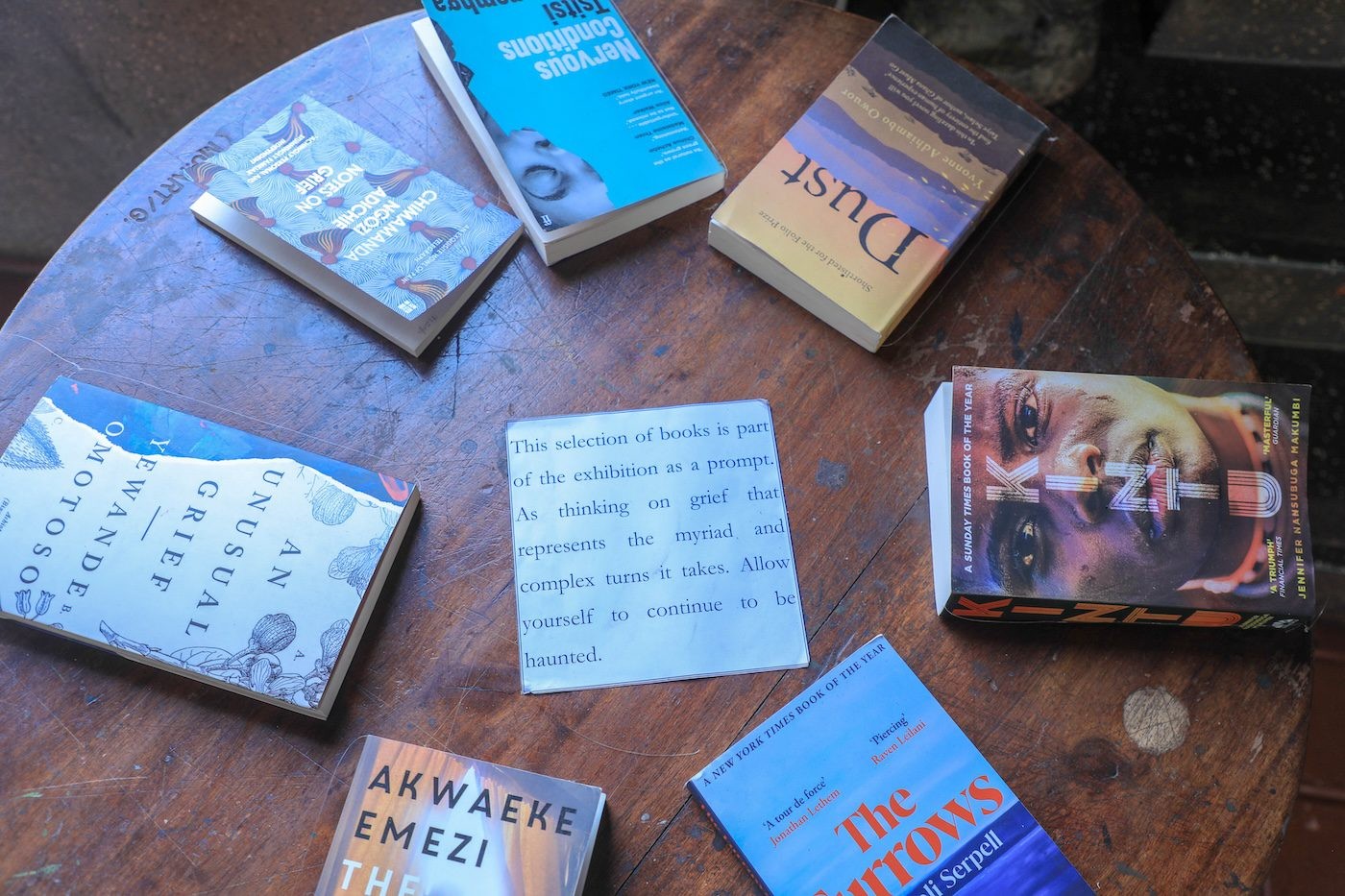

Table of companion reads at Njabala Foundation. Photo: Royal Kenogo.

For me, I found the exhibition an earthing rod for some of my personal, relational, and communal grief(s). A way to come into contact with feelings I hadn’t attended to. To think with Tina Campt and thepodcast you recommended in which Campt says:

I invite people to think counterintuitively, to use different senses to engage or respond to images which we think of as primarily something we see . . . to allow themselves to encounter images as if they were sound. For sound to actually resonate, for us to hear it, it has to make physical contact with us . . . that we are responding to an enormous amount of stimuli memories.

And so, having experienced the images as “felt sound,” I share some sensory notes:

Charity Atukunda’s works on canvas Joy and Sorrow (2024) and Dreamscape: A meeting point (2024) appear in my mind’s eye next to the poem From Blossoms by Li-Young Lee, at a conflux of the ritual of mourning and making meaning of what remains.

O, to take what we love inside, to carry within us an orchard, to eatnot only the skin but the shade,not only the sugar but the days . . .

Helena Uambembe, In memory We love, 2022. Installation view at Njabala Foundation. Photo: Royal Kenogo.

Helena Uambembe’s installation In memory we love (2022) felt like a moment I could climb into, familiar in its presentation of the wake, its aesthetics, the plastic flowers, plastic seats, candles, a blurring together of a memory (hers and mine) of an obituary read and loss revisited. . . there, far in Pomfret, South Africa’s North West province, for me closer in Siaya, in the Western part of Kenya.

Lerato Shadi, River of Thoughts, 2024. Installation view at Njabala Foundation. Photo: Royal Kenogo.

Lerato Shadi’s Gata le nna, gape (2024), red pen on raw linen, and Wambui Kamiru’s video work London Bridge Window (2022) evoked for me an awareness of time in different ways.

In Shadi’s work I was moved by a repetitive gesture that from afar looked like red thread sown onto the linen, and more closely is text written and overwritten, illegible to me, and yet the shapes of the letters familiar. I initially I thought to myself, if I try hard enough maybe I can read to understand, but I soon understood that that isn’t what the work was asking of me. Text inscribed and legibility denied. And so I find another way in, I imagine the process, the movement of the red pen over the sand-coloured linen, in smooth overlapping curves, over and over and over, and a calmness arrives.

It’s a familiar rhythmic language as I approach the video work London Bridge Window in the next room. And yet there are also subtle shifts in the blinking memory of a photo taken out of the same window every day over a month. Each day anew; the differing quality of light in the transition of dawn to dusk, a cloudy horizon, a window wet with rain, diffused sun rays between two buildings, and on and on. A little surprise in one, a hazy reflection of the photographer caught in the window; to not only be an observer but also in the moment of the memory.

Liz Kobusinge, A garden is a grave, 2024. Installation view at Njabala Foundation. Photo: Royal Kenogo.

Liz Kobusinge’s installation A garden is a grave (2024) made me consider the colors of grief. In the daytime, the room bathed in red light in a way that brought me into my body, its veins, its blood-carrying veins. As the video played over botanic dyed bark-cloth paper, installed to hang from above and on the wall, as light bounced unevenly on the surface of the mediating bark cloth, it made me think of grief as a shape-shifter.

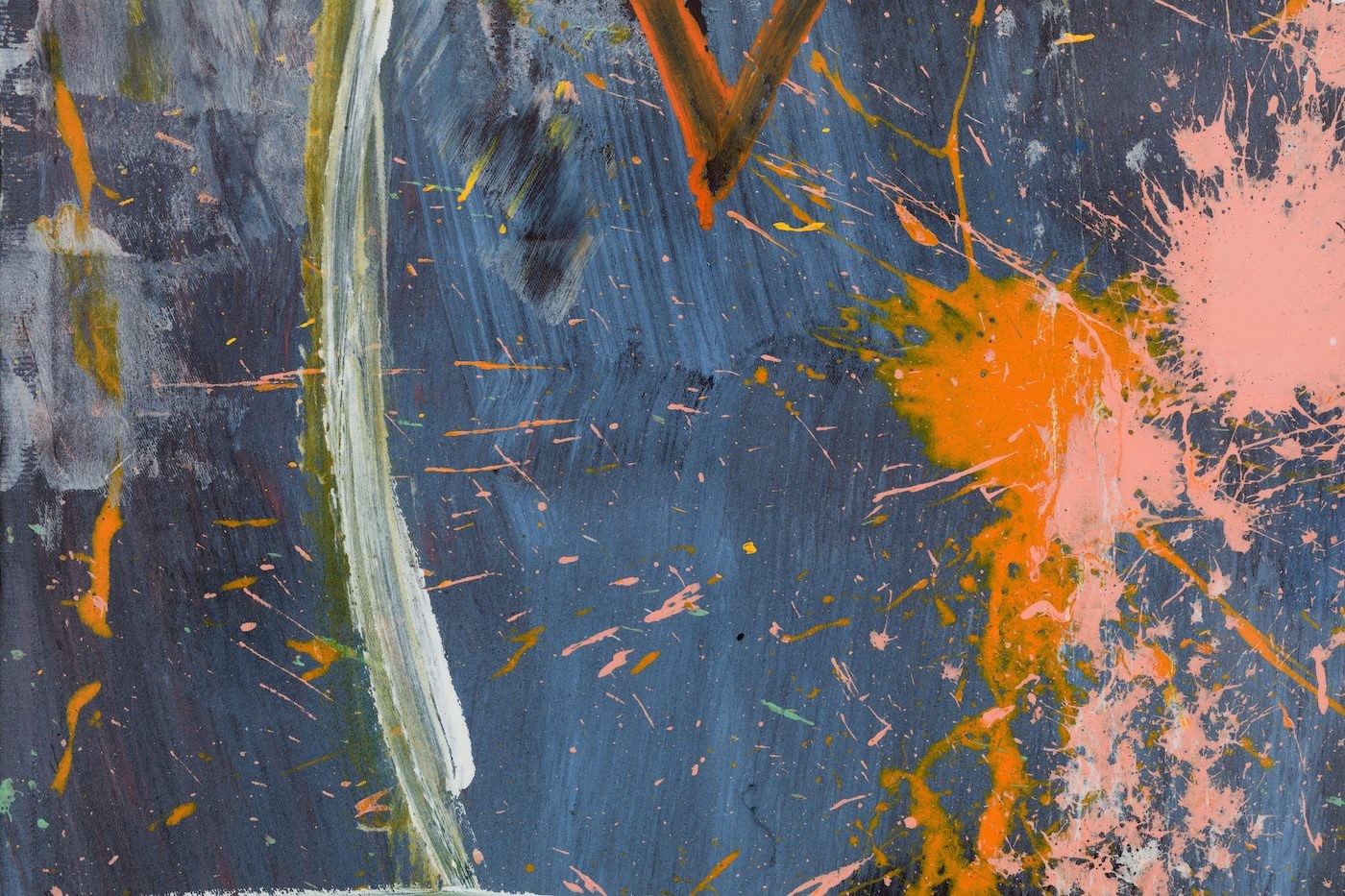

Installation view of Njabala: An Elegy at Njabala Foundation. Works on canvas by Letaru Dralega, text by Twasiima Bigirwa. Photo: Royal Kenogo.

And Letaru Dralega’s mixed-media works made me think of grief’s textures. The mixed media works are made through a process of controlled pouring, but the material reactions end up being their own, pushing and pulling and finally resolving into patterns that mimic so much from life, most notably textured aerial views of the earth. Letaru says, “for me the process of the making is what is important, the same as making sense of the process of grief. A process of finding language for all of us.” If I could run my fingers over the joints, folds, knots, scars, swirls,in the work You give me drinking water (Mi fe mani yi mvuza) what new things might I learn from this contact?

I carried away the catalogue to share the next time I see you and would love to hear what comes up for you when you see the work. Also hoping to get some installation shots sent my way, which will then make their way to you. I know it is a different experience, mediated by a screen, and yet I think so much of its essence will still translate.

I still need to tell you all about the symposium, but let’s leave that for when we see each other. For now simply to say, it meant so much to have it close, here in Kampala, for this to be the centre. To be in community with thoughtful and kind practitioners traveling in from close and far, each one deeply invested in the work of inhabiting and honouring the artistic and literary practices of African women over the decades. Magic. The phenomenal Njabala and AWARE team said that the lectures and panel discussions will all be online soon and I’m so geeked. I know you will be too.

More soon,

Always, always, always,

Rosie

Rosie Olang’ Odhiambo is a writer, artist and independent curator living and working in Nairobi, Kenya.

from

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

from

Visual art

Samson Mnisi: A Master Posthumously Receives His Due

Ladji Diaby’s Sampling Sensibilities Are Material and Time-Bending