In this series, C& is revisiting the most discussed, loved, hated, thought-provoking, and game-changing exhibitions featuring contemporary art from African perspectives in the past decades. We take a closer look at the exhibition Africa Explores, which remains polarizing as a subject of curatorial and art-historical debates.

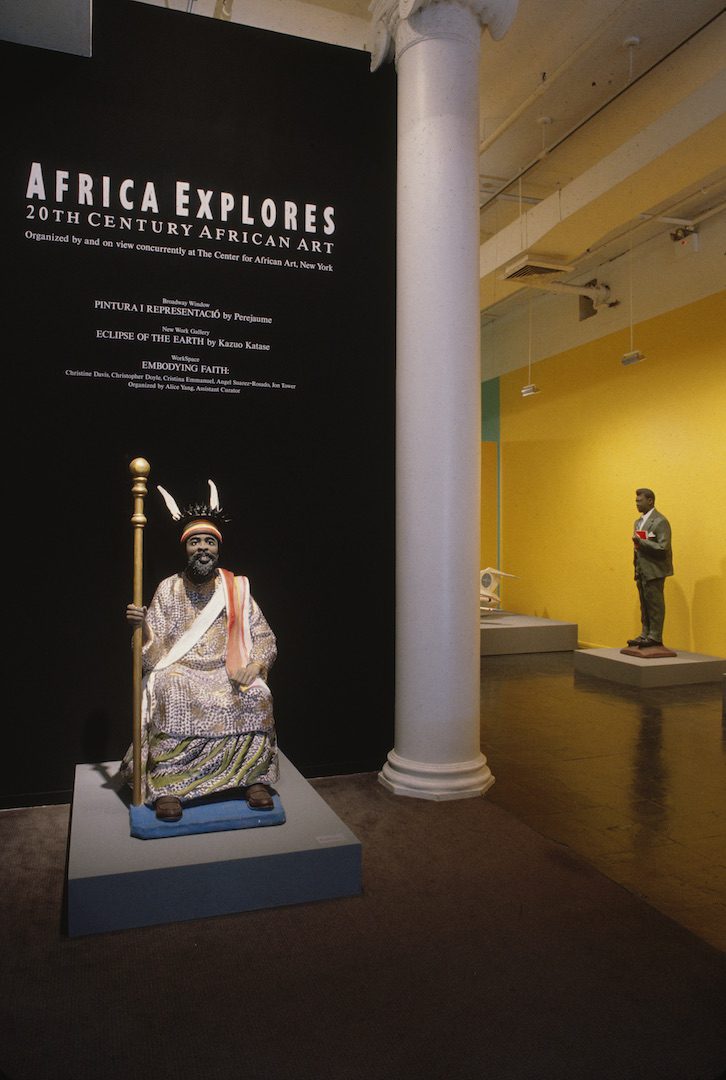

Installation view of Sunday Jack Akpan and Kane Kwei Carpentry Workshop in Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, New York 1991. Courtesy of New Museum, New York. Photo: Fred Scruton

In May 1991, the exhibition titled Africa Explores opened in New York. Curator Susan Vogel presented more than 130 highly diverse works from 15 African countries in the Museum for African Art and the New Museum of Contemporary Art. With a mixture of different media and styles, Africa Explores set out to retell the story of 20th century art production in Africa from the perspective of the continent itself.

Concept and critical review

In both museums, visitors were greeted by life-sized objects at the entrance to the exhibition: a seated chief made of painted cement by the Nigerian artist Sunday Jack Akpan inaugurated the exhibition; next to this figure, coffins in the shape of cars, vegetables, or airplanes, sold in Ghana by the Kane Kwei Carpentry Workshop since the 1950s, were on display. The selection of these works made it clear right from the start that Susan Vogel, then director of the Museum for African Art, did not want to limit herself to one form of creative work. On the contrary, Africa Explores was about showing different art styles which, according to Vogel, equally represented 20th century art practice in Africa. In the exhibition catalogue the curator describes five types of art which she was able to identify in her research: first of all, Traditional art, which was primarily practiced within ethnic groups and aimed to fulfill a particular purpose, such as masks used in certain rituals. Vogel outlines New functional art as a new, eclectic form of this traditional art, making use of all kinds of materials and motives. Popular art or Urban art represented the artisanal, commercial work by self-taught sign painters and graphic designers, while International art stood for the works of urban academic artists. Finally, with ‘Extinct’ art the curator defines traditional art of the past, stored both in collective memory and museum collections.(1)

.

Entrance to the exhibition Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, New York 1991. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Fred Scruton

.

Although the selection of works turned out to be rather heterogeneous, Susan Vogel was aiming to present a particular perspective with her exhibition: “’Africa Explores’ seeks to focus on Africa, its concerns, and its art and artists in their own contexts and in their own voices.”(2) Instead of arguing from a ‘Western’ perspective like the preceding exhibition Magiciens de la Terre had done, Susan Vogel’s goal was to communicate the artworks through the experiences and viewpoints of African artists.(3) However, this intention did not become clear in the exhibition.

The categories Vogel established in her exhibition prompted some criticism. The attempt to suggest they were conclusive and justified could not hide the fact that her definitions were actually quite random, outdated and narrow. Both Olu Oguibe and Okwui Enwezor saw them as instruments of an anthropological classification that had little to do with art history.(4) The large number of autodidactic works and the absence of North-African artists in the exhibition were also indicative of an unreflected ethnological interest reinforcing the stereotype of ‘authentic African art’.(5)

.

Installation view of Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, New York 1991. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Fred Scruton

.

The categories also revealed Susan Vogel’s levity in promoting the supposed ‘African perspective’ of this exhibition. As John Picton pointed out, her classifications were no more than curatorial tools in order to serve the artworks to the audience in the form of easily digestible nibbles.(6) They were developed in and by ‘Western’ institutions and therefore had nothing to do with the perspectives of the artists from Africa. Vogel’s announcement that, as the title suggested, Africa Explores would present a different perspective than that of the exhibition maker herself remained an empty promise. Even the contributions by V. Y. Mudimbe and Ima Ebong precautiously included in the exhibition catalogue could not hide this fact. In the publication Susan Vogel even admitted that – owed to the situation – mainly American authors got to have their say; but she described these and herself as ‘intimate outsiders’. Considering the exhibition concept of Africa Explores, the irony of this term cannot be missed. Here the role of the outsider was not assigned to the curator or her colleagues but to the African artists. Oguibe also comments on this: “The invited insider is only a stranger in his own discourse, swamped and drowned out. It is the ‘intimate outsider’ who truly is in charge.”(7) And in Africa Explores this outsider provided nothing more than an easily digestible, categorized world view in which the actual protagonists were only background actors.

.

Installation view of Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, New York 1991. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Fred Scruton

.

Relevance

Africa Explores was the first large and influential exhibition in the US to engage with 20th century art production in Africa. Even though criticized by many, curator Susan Vogel was still able to shake up the Euro-American art monopoly and to further the fame of artists that are renowned today, such as Chéri Samba or Seydou Keïta.(8) Like many other curators dealing with the presentation of ‘non-Western’ art, Susan Vogel also did not see Africa Explores as an isolated project but as part of a process which was intended to inspire further research and exhibitions (9). The show actually contributed to the discourse and prompted other exhibitions, such as Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa. If nothing else, these exhibitions wanted to reverse the questionable approach of Africa Explores and further paved the way for a global art history.

Participating artists:

Ajani (Nigeria), Sunday Jack Akpan (Nigeria), Kojo Anokye (Ghana), Fode Camara (Senegal), Sokari Douglas Camp (Nigeria), Dame Gueye (Senegal), Kweku Kakanu (Ghana), Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Koffi Kouakou (Côte d’Ivoire), Kane Kwei (Ghana), Albert Lubaki (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Gora M’Bengue (Senegal), Kivuthi Mbuno (Kenya), Middle Art (Nigeria), Moké (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Mode Muntu (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Iba N’Diaye (Senegal), S.T. Ngui, Malangatana Valente Ngwenya (Mozambique), Nsedu (Nigeria)

Tshyela Ntendu (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Magdelene Odundo (Kenya), Ouattara Watts (Côte d’Ivoire), Trigo Piula (Democratic Republic of the Congo), S. Rufisque (Senegal), Chéri Samba (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Sim Simaro (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Samba Sylla (Senegal)

.

Julia Friedel is the research curator for the African section at the Weltkulturenmuseum and writer, living in Offenbach am Main. She studied African languages, literature and art (Bayreuth) and curation (Frankfurt am Main).

.

Further reading and online links:

Okwui Enwezor, 2009: Contemporary African Art since 1980

Simon Hilton-Smith: African Art?

Olu Oguibe, 1993: Africa Explores. 20th Century African Art

in African Arts, Vol. 26, Nr. 1, S. 16-22.

John Picton, 1993: In Vogue, or The Flavour of the Month: The New Way to Wear Black

Susan Vogel, 1991: Africa Explores, New York: Prestel Publications.

.

(1) cf. Vogel 1991: 10 et seqq.

(2) Vogel 1991: 9.

(3) cf. Vogel 1991: 9 and 12.

(4) cf. Oguibe 1993: 22 and Enwezor 2009: 16.

(5) cf. Hilton-Smith: 3 et seqq.

(6) cf. Picton 1993: 98.

(7) Oguibe 1993: 16.

(8) cf. Picton 1993: 97.

(9) cf. Vogel, 1991 : p. 12.

EXHIBITION HISTORIES

LATEST EDITORIAL

More Editorial