Our author Houghton Kinsman takes a closer look at Johannesburg's undergoing urban renewal, especially in its arts precincts like Maboneng and Newtown ...

Arts on Main in the Maboneng Precinct. © Fehmz

At the heart of Africa’s current and highly diverse artistic production has been the reinforcing of major African cities as cultural capitals. From Lagos to Nairobi, Dakar to Harare and Luanda – which served as the inspiration behind the Golden Lion Award Angola received at the 2013 Venice Biennale – these cities have become the urban impetus behind the growth of the African continent both economically and artistically. Cameroonian philosopher and critic Achille Mbembe uses the term “afropolis” to refer to these major African cities as cosmopolitan spaces implicated in and shaped by complex, skewed and asymmetrical global flows of ideas, goods, capital, and people.1

By providing inspiration, preserving history and encouraging cultural participation, these cities have an increasingly multifaceted role in helping shape their country’s artistic discourse. The city’s ability to provide access to museums, its urban atmosphere and cultural, political and religious diversity are but a few of the factors that characterize a city’s influence on creative practice. Therefore, as these major African cities undergo renewal in order to provide the necessary infrastructure to position themselves as “global African cities,” questions inevitably arise over the consequent implications associated with urban redevelopment.

The dichotomy that exists between renewal and preservation within this discussion is a compelling phenomenon that can arguably be seen nowhere more pertinently than in Johannesburg. Long since considered a major economic and cultural city in South Africa, Johannesburg has and is undergoing continued urban renewal, especially in its arts precincts like Maboneng and Newtown. Mirroring major urban redevelopment in international cities such as Berlin, New York and London, Johannesburg is beginning to find success in reimagining its cultural landscape, in speaking with current Johannesburg mayor Mpho Parks Tau, it is “a city at work to remake itself.” As a result, Maboneng has blossomed into a – privately developed – arts mecca with lofts, chic cafés and independent movie theatres, and after numerous failed redevelopments, Newtown is finally beginning to realize its potential as the precinct awaits the R1.3 billion Newtown Junction shopping center. This reinvigoration – of Newtown in particular – which was conceptualized as early as 2005, has seemingly done wonders for the cultural and artistic climate of the city.

“It (Newtown) is an area where everyone can participate in the burgeoning arts scene regardless of social status or wealth,” says editor of Epicure and Culture, Jessica Festa.

Newtown, born out of disaster – a deliberate fire in 1904 destroyed the original precinct – has continually welcomed the creative class ever since the early 1970’s when a host of creatives moved into abandoned industrial buildings in the area, ultimately sparking its cultural development, which has since seen it flourish into what many consider to be Johannesburg’s chief arts precinct.

“We loved being in Newtown and consider it one of the best places for culture in Johannesburg and I really think of it as the heart of the city,” says deputy Director of the French Institute, Denis Charles Courdent.

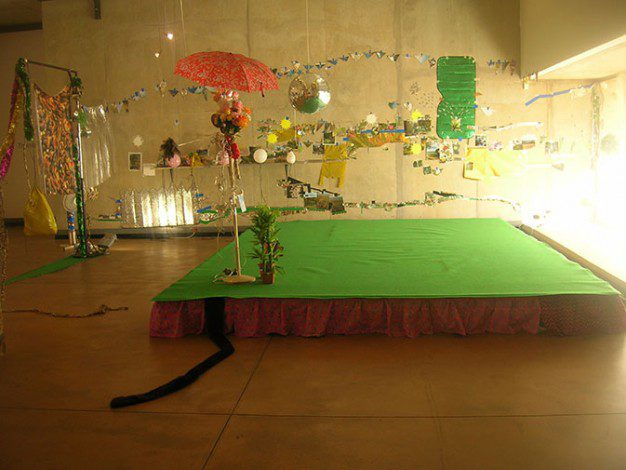

Artist such as Dineo S. Bopape are represented by Stevenson Gallery. The image captures the 2008-installation “grass green/sky blue (because you stood in the highest court in the land and insisted on your humanity)”. Courtesy of the artist.

Playing host to numerous museums, galleries, and cultural spaces – most of which have either been initiated or redeveloped in accordance with the renewal programme – Newtown now boasts institutions such as Museum Africa, alongside the historic Market Theatre and Mary Fitzgerald square, with Goodman and Stevenson galleries nearby in Parkwood and Braamfontein respectively. Additionally, the precinct has recently welcomed the Turbine Hall Art Fair – an event that arguably best embodies Newtown’s transformation, having developed out of renovations to the precinct’s iconic Turbine Hall. With the fair established in order to highlight local young emerging artists, it serves as a reminder of the reciprocal relationship between artist and city. Consequently, it is no surprise that the development of Newtown’s creative landscape continues to have a significant impact on those working in the city.

Statue of an Eland in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, South Africa. (Image courtesy of NJR ZA)

“My work would constitute itself differently if the context and environment changed,” says Mohau Modisakeng, a young emerging artist living in the city. Modisakeng’s belief that Johannesburg now exists as a “confluence of otherwise removed cultural influences,” reinforces the significance of places like Newtown for the city in providing an “environment with various cultures converging in one place.” Therefore, considering Modisakeng’s belief and the noteworthy changes to the cultural infrastructure, on the surface this transformation seemingly benefits all. Artists, city officials, citizens and tourists alike now have access to new buildings, culturally invigorated spaces and hubs like the Goethe-Institut, encouraging artistic/creative dialogue.

Yet, still inexorable concerns continue to arise over the political and social implications relating to the city’s transformation. Unsurprisingly, it is the issue of displacement that remains a major concern. Mail and Guardian writer Stefanie Jason believes the Johannesburg’s situation forms part of “the urban renewal narrative,” where an “artist moves into a derelict space; this attracts property developers who renovate the building and increase the rent; the creatives – along with the long-term residents – vacate or are evicted from the building.” This modus operandi has seen an increase in creatives and locals, like actress Honey Makwakwa and BLK JCKS drummer Tshepang Ramboa, forced to find alternative spaces to live and work, as property valuation increases. “The city [of Johannesburg] has revalued … and basically shot its value through the roof – making the rates and taxes unaffordable,”says Makwakwa in an interview with the Mail and Guardian.

Makwakwa’s sentiments serve to reinforce the double-edged nature of the city’s redevelopment. On one hand it has done wonders for Johannesburg’s cultural atmosphere with precincts like Newtown now thriving artistically, but it hasn’t come without the unavoidable ramifications often associated with gentrification. Ultimately, the conundrum remains of how to equally include the various demographics of the community, especially considering South Africa’s not too distant past, one that is littered with forced removals, issues of displacement and ethnic separation. Perhaps for now, settling with Ramboa’s belief that we “can’t stop change from happening. It’s a part of life. People come and go,” as a placation, seems like a temporary, albeit ineffective resolution.

This major conundrum aside, there is a palpable air of enthusiasm about Johannesburg. Now considered by Phaidon to be one of their 12 Art Cities of the Future, Johannesburg continues to reinvigorate itself, subsequently enhancing its reputation as a “global African city,“ and in turn continues to ensure added impetus to South Africa’s ever-growing and expanding artistic and cultural atmosphere.

1. Lemu, Massa, “Danfo, Molue and the Afropolitan Experience in Emeka Ogboh’s Soundscapes.” Art and Education: http://www.artandeducation.net. 16 July 2014.

Houghton Kinsman is a creative/educator based in Cape Town and Miami and has worked as the Assistant to the Curator of Education at the Museum of Contemporary Art Miami. He contributes regularly to Highsnobiety and Art South Africa magazines.

More Editorial