Despite having had limited cultural exchange, the continents of Africa and Oceania are connected via similar histories of colonialism. The specificities of these are themes that several Aboriginal, Black and Pacific Islands artists have been exploring in order to revive history, keep indigenous cultures alive and imagine their own futures. The series Over the Radar is dedicated to them. First up here is visual artist Tony Albert, who challenges perceptions and stereotypes of Aboriginality in Australia. He is participating in the current Biennale of Sydney, which is led by the event’s first Indigenous artistic director and focuses on Indigenous and First Nations artists. With C& he talks about commonalities of Diaspora, how innocent childhood perspectives change, and how he creates new conversations with the use of text.

Tony Albert, David C Collins and Kieran Lawson 'Warakurna Superheroes #1', 2017. Archival pigment print on paper, 100 x 150 cm. Courtesy of Sullivan+Strumpf

C&: Can you talk about the conditions you are facing in your homeland and the motives behind your work?

Tony Albert: My work has always been personal, attached to my life, but reflective of an Aboriginal experience of living and working in Australia. It started from the very innocent perspective of a boy living in suburban Brisbane, growing and changing as I travelled and continued educating myself both nationally and internationally. I really see my work now as a vessel for storytelling. It is important for me to challenge perceptions and stereotypes. Aboriginal people represent the oldest living surviving culture in the world, and this is something that we should all be proud of and celebrate. A lot of times my works looks at optimism in the face of adversity.

Tony Albert, Mid Century Modern in Collaboration with Katherine Shepherd, Warakurna, 2017. Acrylic and photographic print on archival paper, 35 x 35.5 cm. Courtesy of Sullivan+Strumpf

C&: You are a collector of collective memories and nostalgic memories of your own childhood. What do you find in the objects that make up your collection of Aboriginalia, which you started in 1988?

TA: At the risk of sounding repetitive, the collection also started from an innocent childhood perspective. I came across this discarded ephemera in secondhand shops (a weekly ritual) and fell in love with it. It represented my family and the people I loved that surrounded me. The objects and the images of Aboriginal people are beautiful. As the collection grew, so did I. I started to understand its problematic undertones. I have had to reconcile with the nature of the collection as I got to know more about it, but also understand the social, political and environmental aspects. I am ever fascinated by the collection and it is still growing. While a lot of the work I do with the collection is hard-hitting, a little bit of me that still looks at the imagery through the loving eyes of my childhood. It is this juxtaposition and tension which fascinates me.

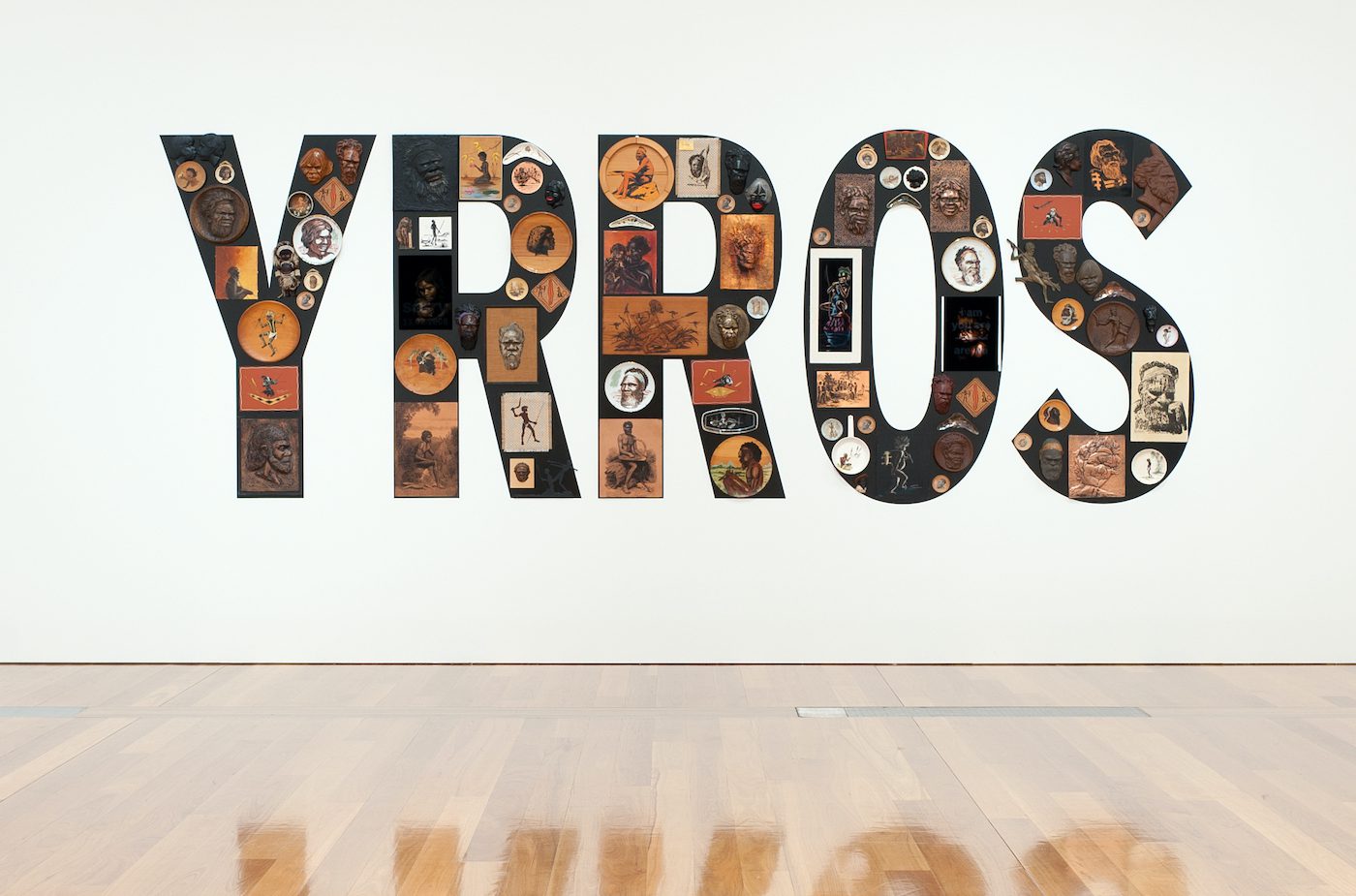

C&: Works like Sorry (2008) or Headhunter (2007) use the collection to form text. What do language, words, and writing mean to you?

TA: Language is a fundamental and universal tool in communication. Words play a big part in my practice. They are an instant way to engage with the audience. The work can be read as a word from a distance and then change as you get closer and start to see all the objects that make up the collection. Then you get closer still and see the small interventions made to the objects. The twists, turns, and nuances associated with language create unique conversations.

Tony Albert, Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku Yalanji peoples Australia QLD/NSW b.1981, Sorry, 2008. Found kitsch objects applied to vinyl letters, 99 objects: 200 x 510 x 10cm (installed). The James C. Sourris Collection. Purchased 2008 with funds from James C. Sourris through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Collection: Queensland Art Gallery

C&: The year 2020 marks the 250th anniversary of British “explorer” Captain Cook’s arrival in Australia. In 2008, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made an apology to Australia’s Indigenous peoples, in particular to the Stolen Generations. Can you share your thoughts on this apology, in the context of your work Sorry from 2008?

TA: Sorry was a commission for a 2008 exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery titled Optimism. It was also the year that Kevin Rudd apologized to the Stolen Generations. The important thing to remember is that “sorry” is just a word. It is the actions and reactions of an apology that make it meaningful. The work has been exhibited multiple times since that exhibition, and I have asked that it be hung backwards. This goes back to the intervention into language – what it means when you see words written backwards and upside down.

C&: Some of the “Aboriginalia” objects you collected are little child figures. I recently read that Australian tourist markets use recycled African-American child figures to sell as “Aboriginal” souvenirs. There is so much to read in this – besides a very racist idea of “color,” it also points to a certain connection. These linkages are also part of the concept of this year’s Biennale of Sydney, NIRIN, which includes many artists from the Global South. How much can you relate to the experiences of artists from Africa and the global Diaspora?

TA: The more opportunity I have had to travel the more I have experienced international race relations. There is definitely a Diaspora attached to people of color and connecting them. The peripheries and edges of society all have commonalities. This is not to discount the privilege and power attached to whiteness, advantage should be looked at equally to disadvantage. Equality for me exists within expectance of difference, not through things being the same. NIRIN, under the directorship of Indigenous artist and curator Brook Andrew, is so important. It challenges social norms and tells a version of history and historical truth that is not represented in the mainstream. Its a biennial that people don’t just see, but take the time to listen to.

Take an online tour of Tony Albert’s work and many more impressions of the Biennale of Sydney here.

Tony Albert was born in 1981 in Townsville, QLD, Australia. Over the past 10 years he has achieved extraordinary visibility and much critical acclaim for his visual art practice, which combines text, video, drawing, painting and three-dimensional objects. In 2014 Albert was awarded the Basil Sellers Art Prize and the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award. In 2015 he was awarded a prestigious residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in New York and unveiled a major new monument in Sydney’s Hyde Park dedicated to Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander military service. He was also awarded the 2016 Fleurieu Art Prize, with his winning work, The Hand You’re Dealt. Albert’s work can be seen in major national and international museums and private collections.

Interview by Theresa Sigmund.

OVER THE RADAR

LATEST EDITORIAL

More Editorial