The 29th Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou, known as FESPACO from its French acronym, was held under the theme of "African Cinemas and Cultural Identities" in February and March 2025. Sharing reflections and excerpts of their visual diary on film, writer Makella Ama explains why FESPACO is distinctive and culturally significant.

Libation March through the city of Ouagadougou during FESPACO 2025. Photo: Makella Ama.

In a dimly lit room, a communion of ears resonates with the sounds of a balafon (balangi, gyil, xylophone), a shekere (beaded gourd, cabasa, axatse), a bendré (bare, djembe, gourd drum), and a kora. We have just watched Denise Fernandes’ Hanami (2024) at Cine Burkina in Ouagadougou, and the reverb that is sharing the space with us, both aural and spiritual, never really dissipates for the entirety of the 29th iteration of the festival.

Hanami by Dir. Denise Fernandes, Switzerland, Portugal, Cape Verde, 96 min, 2024, film still. Courtesy of MoreThan Films.

Since FESPACO’s genesis in 1969 as an affair involving five African countries, namely Burkina Faso, Senegal, Mali, Cameroon, and Niger, the bi-annual festival has grown to include forty-eight countries from across the continent and the Diaspora. Its prestigious awards include the Etalon de Yennenga, named after the warrior princess of the Mossi empire, and the Prix du Public. Alongside its screenings, the festival is characterized by its mixture of workshops encouraging critical discourse, conferences inviting social commentary, libation ceremonies, and marches through the city.

FESPACO began as a week-long gathering by fifteen African film enthusiasts, including François Bassolet, Claude Prieux, Alimata Salembéré, and Ousmane Sembene, who wanted to watch African films by African filmmakers. Diaspora has always been a key part of the festival, as evident in the inclusion of films such as Losing Ground by Kathleen Collins (US, 1982), Burning an Illusion by Menelik Shabazz (Barbados, 1981), and Rue Casre Negres by Euzhan Palcy (Martinique, 1983).

A growing contention regarding France’s monopoly of film distribution, resulted in African films only being shown in European contexts and being banned from screenings in African countries, as explored in Camera D’afrique (1983). In a particularly notable part of the film, Med Hondo compares this process to a man who makes babouches or boubous: “if he can neither display nor sell his own work at the market, he is reduced to the status of a dumb consumer. Why import boubous when he’s capable of producing them himself? If the market is not controlled! If an African cannot see his own image! He is dominated and alienated.” Film and its distribution have always been political, and African film festivals like FESPACO and Festival International de Carthage (Tunisia) have functioned as seamstresses actively attempting to unravel these politics.

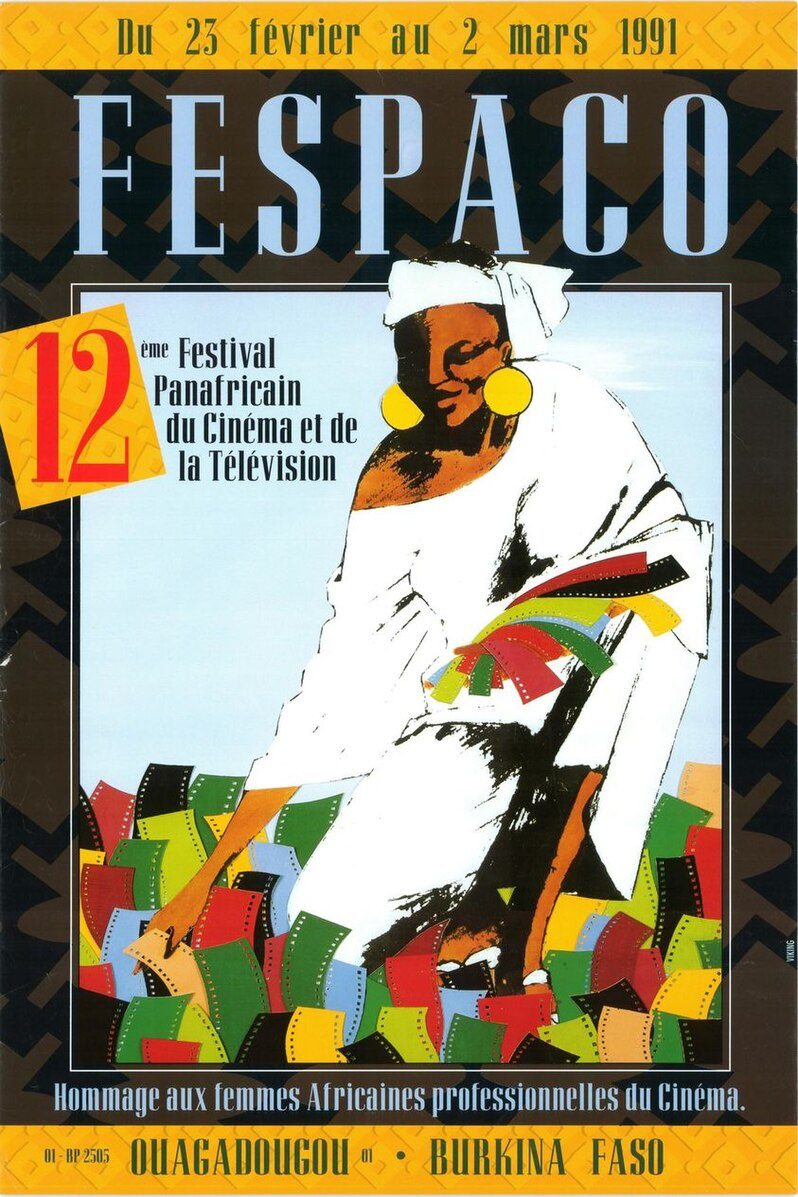

FESPACO poster 1991.

In an era of palpable uncertainty regarding the state of film festivals, FESPACO remains one of the seminal cultural events in Africa and the presence of a charged political backdrop is one that has stayed consistent in its evolution, especially now under the governance of current president Ibrahim Traoré.

This is an important subtext to the festival, as it reminds us that the spirit of FESPACO is one rooted in protest against Eurocentric dictatorship. This spirit of political defiance was initially imbued through the active involvement of revolutionary Burkinabé president Thomas Sankara who challenged culture, corruption and colonisation. Three C’s that have always brought more questions than answers. Before his assassination in 1987, Sankara provided social and financial support and set the theme for the 1985 edition of FESPACO: “Cinema and the Liberation of Peoples.” Sankara, who was also a guitarist in the band Tout-à-Coup Jazz, had an almost spiritual dedication to raising public consciousness about the inherently political nature of art. As he said at the United Nations in 1984, “I speak on behalf of artists… poets, painters, sculptors, musicians and actors… who see their art prostituted by the alchemy of slow-business tricks.” This was a testament in his commitment to raising public consciousness.

Libation March through the city of Ouagadougou during FESPACO 2025. Photo: Makella Ama.

Plausibly, it is this lack of ethos that renders so much of the film industry hollow. Whilst there are continuous calls to action for interventions such as increased pay, rights and working conditions for all stakeholders involved in the production of cinema, it often appears as though these calls, at least, from those with monetary power, are nothing but knee jerk reactions characterised by a lack of genuine belief and willingness to change. This is a significant contrast to figures such as Traoré, who made an appearance during the opening and closing ceremonies of FESPACO and has made efforts to strengthen marginalised local communities and reorient power away from Western elites. Continuing in the legacy of Sankara’s ever-lingering fight against neo-colonialism, Traore’s pledge to African sovereignty was a tangible energy throughout the festival, and warranted the question: if patriotism is still a virtue clung unto by many, perhaps this patriotism should have spirit.

Hunter Warrior Tribe from L’arourie post a Libation March during FESPACO. Photo: Makella Ama.

In embracing the alchemical, and resonant aspects of film, FESPACO’s entire program contains a deep reverence of ceremony. Each edition nominates a guest country of honour, which is reflected a series of activations during the opening ceremony. This year, Chad inaugurated the festival, staging a charged enactment of ceremonial theatre over four hours: A griot taking centre stage in retelling stories of Chadian history / women and men elders locking eyes mid traditional Zaghawa dancing / piercing cries of respect in tribute to Souleymane Cisse’s passing / an orchestra flooding our ears once again / elders perched on elevated chairs overlooking us, as an audience, in deep contemplation / here, we are all watching each other / watching each other / there is an explosive charge in the air / a chant / emphasised reverb echoing around the stadium / slow steady promenades from one side of the stage to the other/an explosion of breakdancers/a customary man/there is always at least one / covered head to toe in yellow paint / and green / and red / another piercing cry / an eruption of applause followed by an eruption of silence upon Ibrahim Traoré taking centre stage / the waving of a flag/the waving of a flag/the waving of a flag.

This spirit spilled out from the opening ceremony and continued across several days onto the streets of Ouagadougou. We would walk home to the sound of a familiar drum echoing through an unidentifiable compound, pass by FESPACO headquarters whose ground were full of families and children, or visit the infamous De Niro’s, stand on one side and order drinks or stand on the other to watch a group of black horses amble up to greet Burkinabe rappers, mid-flow, on pop-up stages.

Stewards at FESPACO Headquarters 2025. Photo: Makella Ama

It was elevating to see the symbiosis of cinema and a true sense of Pan-African culture. For me, film has never just been about film. It’s about the ability to metaphysically travel through space and time, to engage in remembrance, to immerse myself in something other when I am losing touch with things that make me feel alive. Being among the aliveness of Ouagadougou during this time meant that the idea of cinema was not limited to a dark room with four walls and a screen. Cinema occurred in an open-air stadium under the stars amid the sounds of a nearby market. Cinema was happening in the 40-degree heat reminding our skins of what it feels like to drink the color orange. Cinema was happening all around us.

In an age of lecture performances as a testament to a universal desire to share non-passive spaces with people, I wonder how this break in convention can be taken one step further. How can we share spaces with audiences that exist outside the often stiflingly elitist world of art and film? How can we demand more from ourselves, as both spectators and contributors, to the ecology of cinema?

At June Givanni’s Per Ankh exhibition at Raven Row in 2023, Gaston Kabore spoke of ceremony in congregating around a baobab tree — that wasn’t necessarily a tree because it was a table — and how this was a space for spiritually charged conversations about film and its cultures. “People would wait and take turns being invited to the table to speak — it was really about the elders passing traditions on and creating networks.” This speaks to a gradual decline of space to breathe and digest around films. Current cinema culture involves attending a screening and going home, or sitting through a Q&A, the value of which is entirely dependent the questions asked by those present in the room.

I want to make a call for spaces of activation beyond such constraints. Perhaps what many are beginning to lose is a sense of ceremony. If patriotism is still a virtue clung unto by many, maybe this patriotism should have spirit. After all, nothing we do is ever really done alone. Although we are our own sun, as Ousmane Sembene put it back in 1983, we are not suns in isolation. At least, not on cinema grounds.

Makella Ama (b. Accra, Ghana) is an anti-disciplinary maker with a practice that often takes shape through curation, visual anthropology, and writing through a sensorial lens. Their practice is rooted in their background of community/youth work with children in care and young refugees. A question Makella is often grappling with is this: how can we demystify the links between storytelling, history, and the ability to bring archives to life/light/memory?

EXHIBITION HISTORIES

More Editorial