In a subversive reconfiguration of images and objects from his immediate surroundings, artist Ladji Diaby’s solo exhibition “No One Has Ever Called Their Child Hunger” uses photo transfer processes, memes, gaming, video, film stills, and other materials to conjure a cosmos of his own. In an echoing text by Cynthia Igbokwe, we unpack how the artist’s sampling practice breaks out of the “white cube”, into and beyond a “collective common sense”.

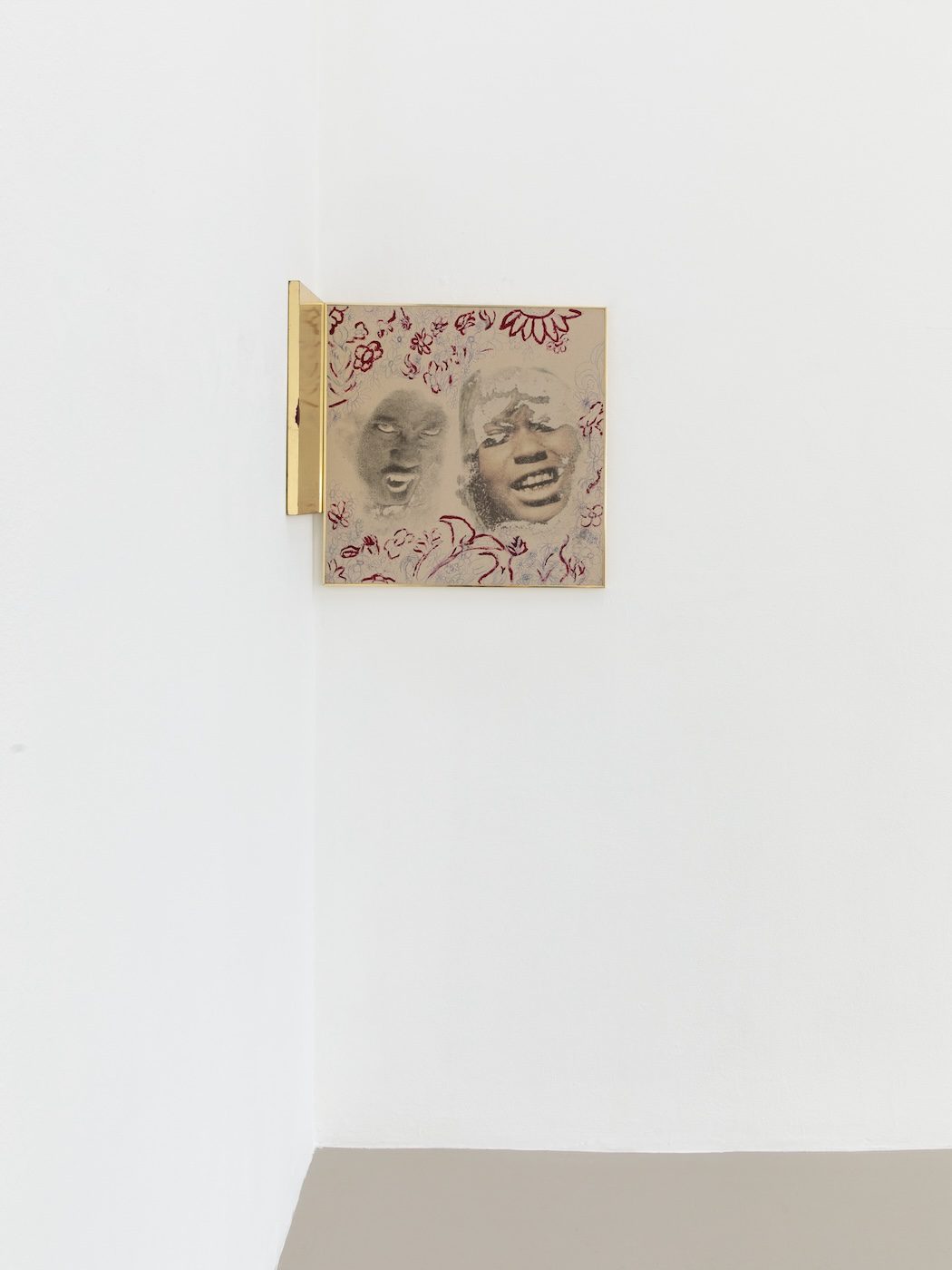

Ladji Diaby, No one has ever called their child hunger, Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2024. Photo: Lukas Pürmayr.

No one has ever called their child hunger. This proverb, shared by a friend after watching Ladji Diaby walk the streets of Dakar, holds a powerful sentiment. A few words, carefully chosen, can convey profound meanings far beyond their apparent simplicity, taking root in our minds like seeds that grow over time into something far greater. Like a proverb, art has the power to evoke one’s own life story in the mind of any viewer. In the case of Ladji’s artistic process, the gathering of everyday objects he finds on the street builds a kind of personal mythology—one that captures the wisdom of a soul passed down through generations.

Ladji Diaby, No one has ever called their child hunger, Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2024. Photo: Lukas Pürmayr.

There is a humility in this kind of work, a reminder that he is not making the rules, but allowing the materials themselves to show him how to use them. They teach him that it is only by accepting limitations that he can find the freedom to experiment and realize the limitless possibilities of what could be. It is within these constraints that radical thought and imagination are born. This approach is not simply about making something out of nothing; it’s about the sensibility of seeing beauty in objects in the moment of encounter. An exploration of what speaks to him in a language beyond words.

Ladji Diaby, No one has ever called their child hunger, Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2024. Photo: Lukas Pürmayr.

Ladji’s prints and sculptural work share something in common with the process of sampling in his music production. By isolating and recombining elements, whether sonic or material, he weaves in pop cultural histories, engaging not only with their aesthetics but also with their impact on our everyday lives. It’s a fascinating process: hearing a fleeting sound, taking a piece of it, looping it, allowing it to take on a life of its own—a new beginning and end, a new feeling that moves you even before you can articulate why. Call it a JDilla-type magic or a happy accident. Ladji’s assembly of objects and imagery captures those unexpected moments, creating a serendipitous effect where the journey to the final piece is as mysterious as the work itself. Sampling, as both technique and stylistic choice, forms a bridge between the past and the present—a continuous exchange of cultural memory, identity, sounds, and images. This work connects on a deeper level because it is rooted in people’s everyday existence and activities, in images that remind us of drawing on bathroom tiles or sitting on our mother’s bed frame at night.

Ladji Diaby, No one has ever called their child hunger, Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2024. Photo: Lukas Pürmayr.

If magic is found in the encounter with an object, then a personal utopia is found in this exhibition. However, this utopia critiques the notion of “art for art’s sake” and instead celebrates the struggles and triumphs of those who came before us. Being a “people’s artist” teaches us how to persevere and remain dignified in “the industry” or “the art world.” Ladji encourages us to imagine new forms of world-building, forms in which the collected materials embody political, literary, musical, and personal influences, creating a new system of meaning that reflects the complexity and diversity of everyday life. We encounter a vivid visual lexicon that allows us to talk about Mike Tyson, Karl Marx, Shinji Ikari, Fredo Santana, and Louis Farrakhan all in the same breath. His drawings and sculptures not only invite us to fill in the gaps, but also propose a remaking of historical images and stereotypes; they subvert context, skin tone, or hair color in the name of self-respect and creating new expressions of pride.

Ladji Diaby, No one has ever called their child hunger, Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2024. Photo: Lukas Pürmayr.

We can learn much from anime about our imaginative and transformative potential, and dedication. Something like the feeling when you realize that your favorite green, blue, or purple anime character somehow feels Black. Or the excitement felt when a protagonist awakens their power system in the training arc and learns to manipulate their own life energy (aura) to defeat an opponent. Or the magic of hearing Susumu Hirasawa’s “Guts” for the first time while watching the anime series Berserk (1997) and experiencing that shock of beauty in response to those moving images.

Ladji Diaby, No one has ever called their child hunger, Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2024. Photo: Lukas Pürmayr.

The diverse influences embedded in Ladji’s practice are a testament to his breaking out of the “white cube”— to the constant struggle to liberate himself while operating within oppressive structures, pushing the boundaries of what is considered acceptable art, and choosing not to conform to Western ideologies that distance people from art.

Ladji Diaby, No one has ever called their child hunger, Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2024. Photo: Lukas Pürmayr.

Ultimately, “no one has ever called their child hunger” goes to show that Ladji’s art is about connection, about being connected to something bigger than oneself. His images remind us of the love and humor shared with friends and family. More than anything, it illustrates that when your world is part of someone else’s, it only makes sense to bring those worlds closer together. This exhibition reflects the depth of a culture and taps into what Stuart Hall describes as a “collective common sense” that “feels like it’s always been there.” Ladji shows us that we don’t have to choose between magic and common sense, because magic is in the process.

His humility when it comes to making art, along with his ongoing practice of recording, sampling, and exchanging the meanings of objects in everyday life, encourages us to imagine new narratives as we make sense of our shared experiences. It’s a journey that requires honesty and integrity, a willingness to fail, to try again, and to fail better. This newfound wisdom invites us to think about new ways of thinking—not only to navigate our realities more joyfully, but to make and remake new ones.

This text was originally published in the exhibition brochure of Ladji Diaby’s solo exhibition No One Has Ever Called Their Child Hunger at Kunstverein Nürnberg.

Cynthia Igbokwe is a London-based curator, researcher, and creative strategist whose work engages with diverse themes in cultural theory through the lens of sonic and visual art.

ALL ABOUT ARCHITECTURE

C&’s second book "All that it holds. Tout ce qu’elle renferme. Tudo o que ela abarca. Todo lo que ella alberga." is a curated selection of texts representing a plurality of voices on contemporary art from Africa and the global diaspora.

More Editorial