Kim M Reynolds dives into the poetic work of multifaceted visual artist Manyaku Mashilo, encountering the possibility of invention.

Manyaku Mashilo makes large-scale figurations that concern themselves with ritual, movement, essence, and paths of becoming for Black people. Born 1991 in Limpopo, raised mostly in Pretoria, and based in Cape Town, South Africa, Mashilo studied fashion and developed a practice of abstracting figures before coming full-time to visual art. She drew silhouettes that moved away from literal renderings of “man” or “woman” toward a non-specific figure, a place. Mashilo’s art practice sustains this abstraction, which poses more questions than answers.

For her latest body of work, An Order of Being, exhibited by Southern Guild Gallery in Cape Town, the exhibition text by Julie Nxadi extends the invitation of inquisition: “The question in these textures is not how did we get here but how will we survive here. Here as in: now, tomorrow, after, freedom – how will we be? We have all known to look to tomorrow in the pit of night before dawn breaks the sky’s surface. Abanye baye ngale abanye ba wele – but today these textures ask: so far, dear traveller, how have you found your way? How does it feel to be here, how will we know when we get there?”

Mashilo tells me that An Order of Being began with her personal life, dreams, and an impetus to create works that facilitate movement and ritual, drawing from remembered experiences with religion, specifically the Zion Christian Church, and spirituality. In this case, utilising memory and is utilising intuition – Mashilo leans into dreams and creates kinds of re-memories that have origin in something real and something lived, but are rendered on the canvas as augmented forms or a modality of rhythm and movement. For her, the capacity for movement and change allows for a way forward in a world made ambiguous and difficult by the hands of colonialism and all other forms of policing an un-softening of the world.

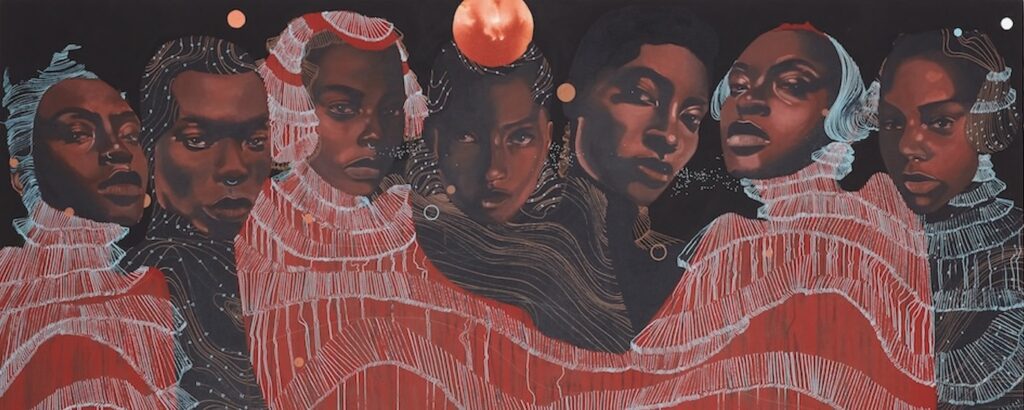

“I’m most liberated when I’m able to change myself, whatever I need to, you know?” the artist tells me. “It used to be something that I was very insecure about before – I was like, “Why can’t you just be one thing? You need to wear black all the time, you need to have one hairstyle.” But I’m just like, that is not in our nature at all. And part of that forward movement is the shapeshifting in identity, in the way we dress, even within our genders. So the character is the same – they shift into these different cosmos, they shift into these different patterns and their meaning and their reason for being in that specific portrait changes all the time.”

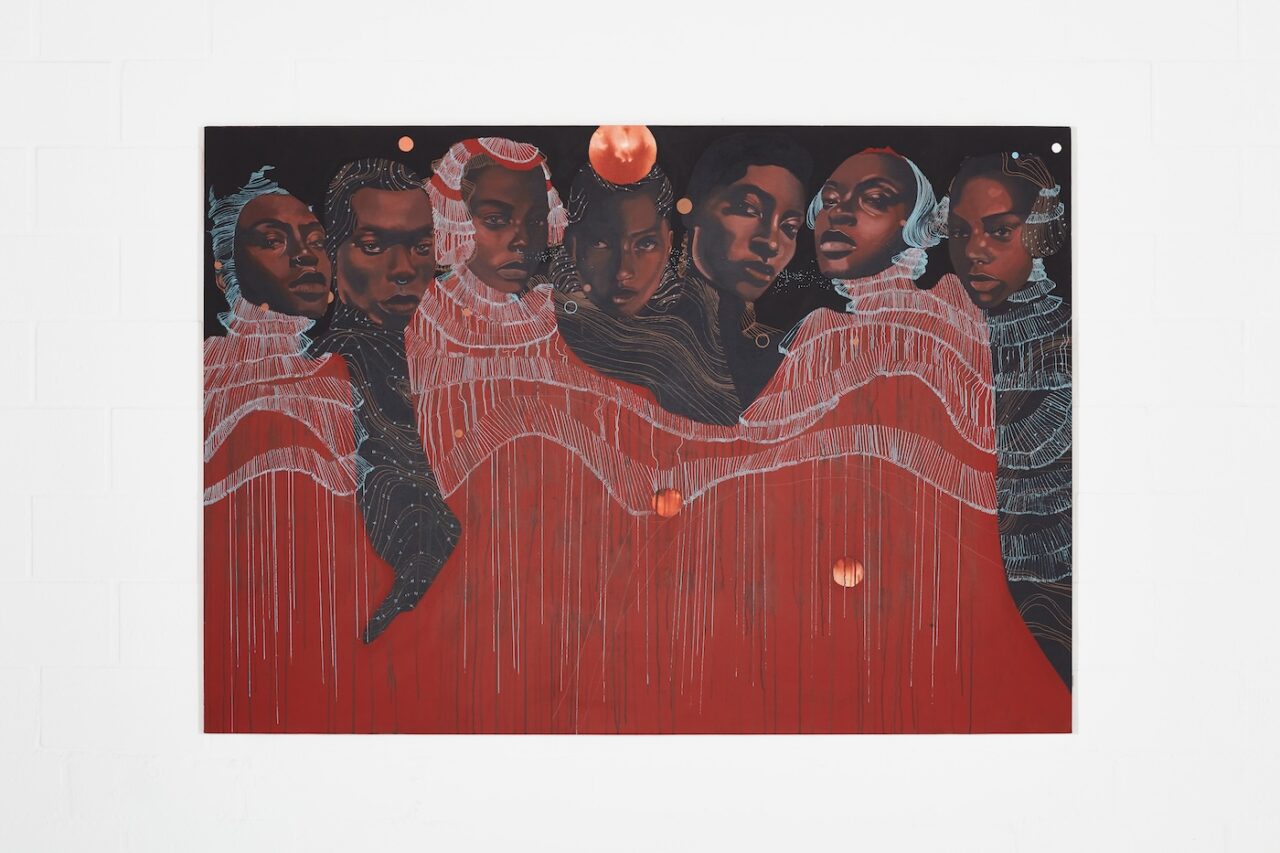

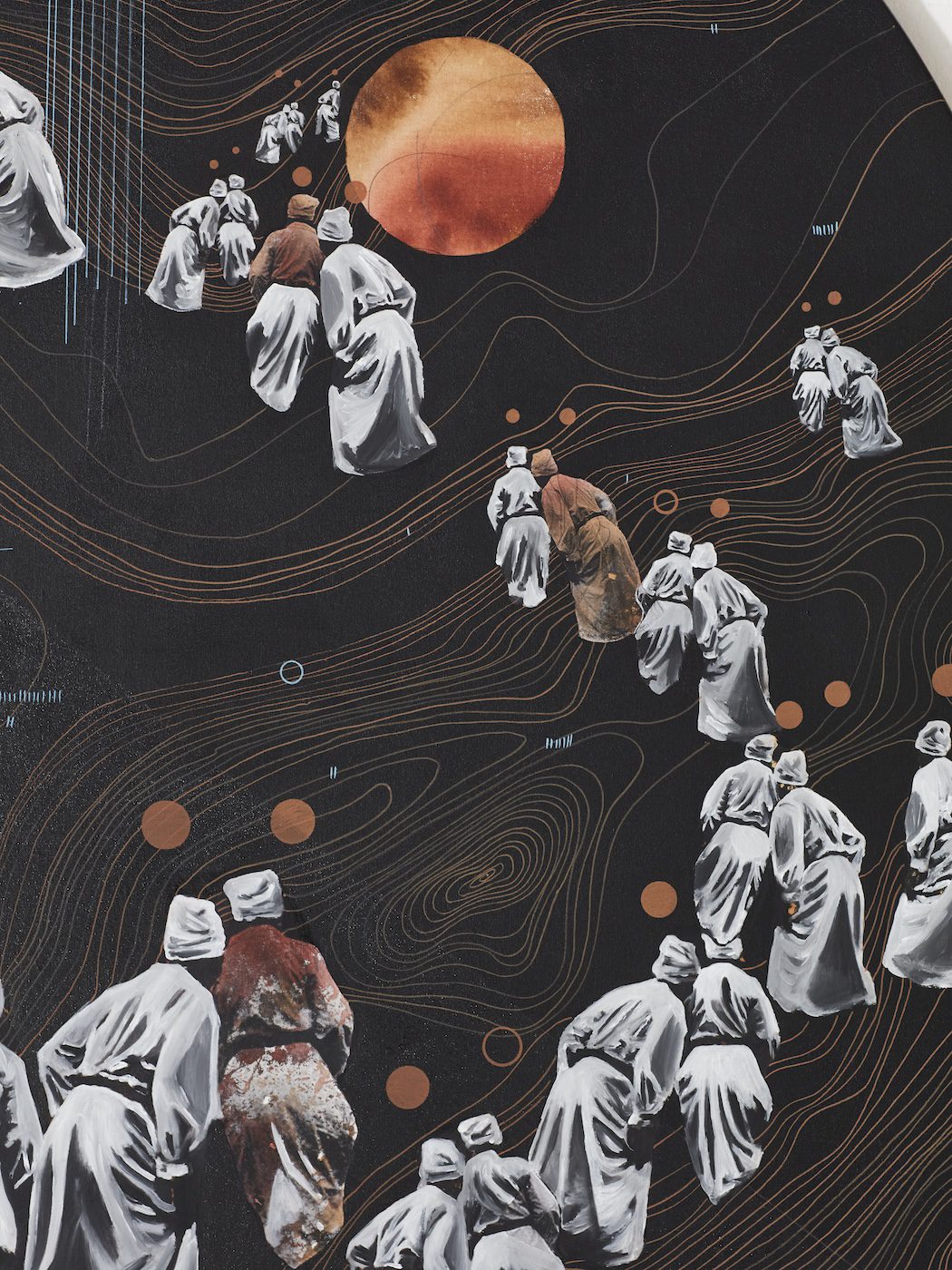

An Order of Being consists of seven large-scale paintings. At one end of the exhibition stood a triptych, almost like an altarpiece, called Passage to Prayer (2023). These three canvases have rounded tops and rectangular bodies, drawing upon the circular nature of rituals as well as the kind of images Mashilo grew up looking at in her grandparents’ home, including a Last Supper – religion and spirituality sit side by side. In the centerpiece, two feminine figures embrace, taking up most of the canvas and inviting the viewer in. In the background several journeying feminine figures are dressed in all white with accompanying white doeks. These figures are influenced by Mashilo’s memories of church and the photography of Santu Mofokeng. Mashilo puts elements of Mofokeng’s stills into motion by positioning the figures as moving toward a center but perhaps also another place to go to and move through. The triptych creates a circular motion: when the viewer steps to the center, the circle is complete and the ritual can begin – or finish.

What propels motion in much Mashilo’s work is repetitive line work. Repetition of a task, song, or prayer can conjure up attention as well as transposition. After one round your attention to detail can be high; after five rounds another element may come to the forefront; after twenty, your intuition may lead you somewhere else, able to leave the realm of the immediate and journey elsewhere. In An Order of Being, drawn lines represent the necessity of repetition, its tie to ritual and in turn to coping and healing.

Mashilo recognizes and interprets this relationship between repetition and ritual, where the repetition of lines composes many types of ceremonial garments in indigenous culture, as well as the repetition of chanting, foot stomping, and singing all come together to make music in various Black and Indigenous practices. She adds: “ And it’s almost like this friction, and the hotter it gets, it needs to combust, and then set you free.”

The lines that run throughout An Order of Being can be seen for what they are – things that connect one point to another. Or they can be seen as mountains. Fingerprints. Directions on a map. The impact of the wind on water. Your way home. Your way out.

Mashilo’s seamless blending of materials reflects this plurality, emphasizing that multiple forces are at play and how intuition can illuminate them and even guide the process. For example, the ink that forms bursting sections of color is shaped by how the water moves on the canvas, which is influenced by how much movement or warmth is in the air, which is determined by the season. The movements of water and ink are also dependent on the floor of the studio Mashilo is working in and how even or odd it may be. Sometimes puddles form when the water sits still; other times less concentrated arrangements appear.

The canvas is also a space representing the land that Black people are Indigenous to and use to live and heal. Mashilo’s figures are Black people with a red-ish undertones, which she creates to represent clay used in rituals and ceremonies, both religious and spiritual. Oftentimes clay is used to renew, where it is applied for the duration of the ceremony (and sometimes after) and later washed away, along with whatever was meant to leave.

What perhaps runs through the work of Mashilo most prominently is the possibility of invention. Mashilo listens to music while working, including jazz, which can drive her movements but also speak directly to the general approach – the brilliance of improvising. Creating on top of a set scale or diverging from it completely can remind us that relief is paramount and can be created. One can relieve oneself from the realities of this world through ritual, through healing, and through other people. Improvising can be abstract and blurry as well as clarifying and exhilarating, in the inuitive musical sense and many others. It can allow one to, as Mashilo says, come to terms, with what has happened – what has happened to you, what has happened to the land under your feet (or lack thereof), what has happened to this earth. Here, improvising, creating, repeating, and ritual are all reminders that the death-oriented world we live in can be made anew, in one realm or another.

Kim M Reynolds is a writer, critical media scholar, and tech researcher from Ohio in the US, based in Cape Town, whose work focuses on the narrative and critique of Black arts and politics. Reynolds is currently a co-lead of US-based research and organizing collective Our Data Bodies.

FEMALE PIONEERS

More Editorial