In his three-decade-long practice and through the use of varied media, the Nigerian artist has intimately reflected on himself and his immediate sociopolitical environments.

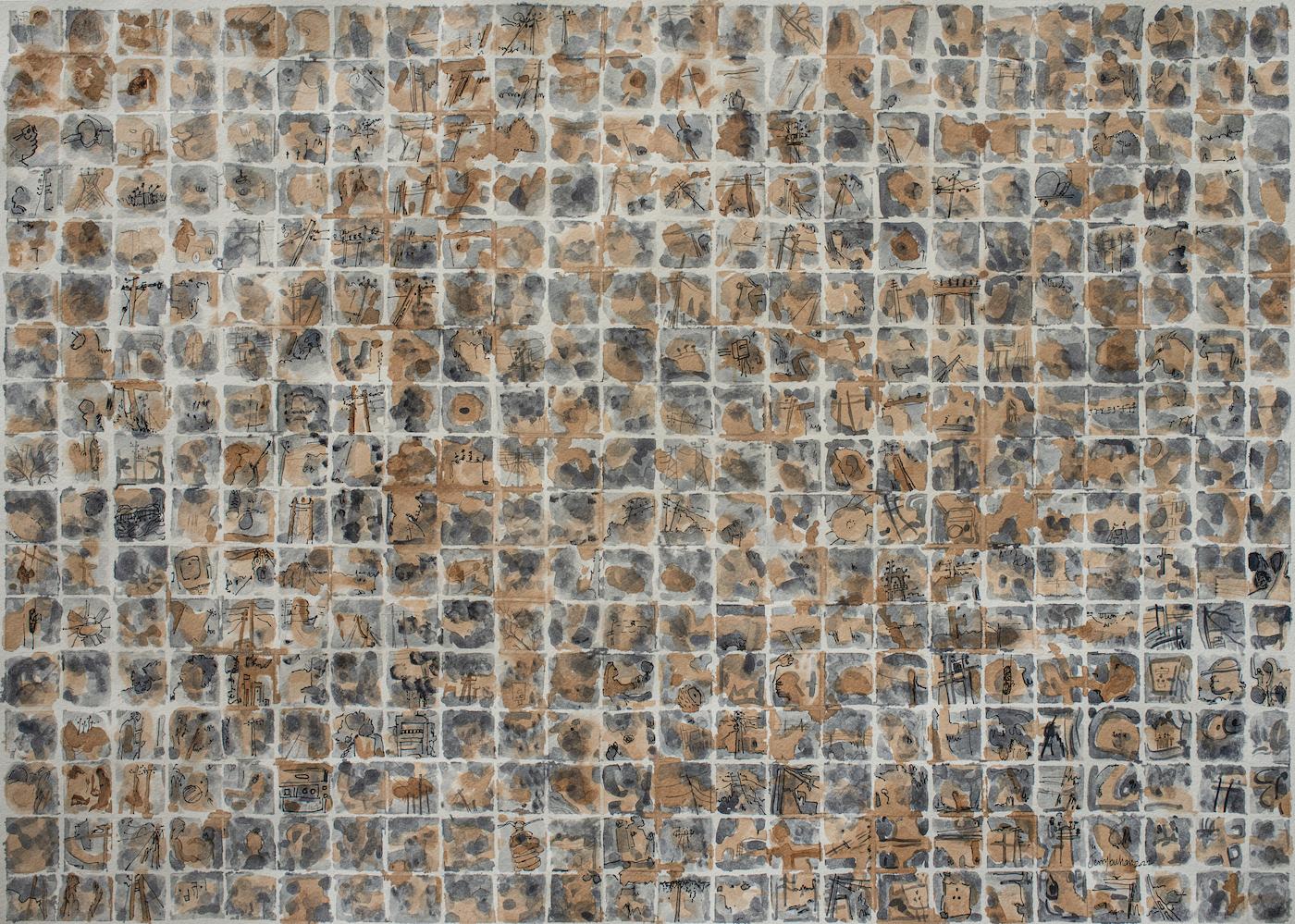

Jerry Buhari, 408 Journals of NEPA, 2022. Mixed media on paper 30 × 22 in | 76.2 × 55.9 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Jerry Buhari is among Nigeria’s most important contemporary artists, with more than sixty group shows and twelve solo exhibitions. He studied in the same pioneer institution’s art department (Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria) as the notable “Zaria rebels” – Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Bruce Onobrakpeya, and Yusuf Grillo – and started his teaching career and studio practice in the early 1980s. A recent retrospective at Kó Art Space Lagos showed the coming together of his work. The exhibition was divided into four categories, Landscapes of the Soul, Earth Media, The Black and White Series, and Mixed Media, encompassing all of Buhari’s studio engagements. Within this structure one witnessed his use of diverse materiality, which serves as a handle to his work. It was not only mediums such as watercolor and ink but more experimental materials such as soil and coffee mixed with glue. Preference for miniatures is a defining style, with some of his picture frames as small as 2 x 2 centimetres, even in this era of large canvases.

Born in 1959, Buhari first made miniature paintings in 1993 from scraps of paper in his studio. “They were inspired by the hardship occasioned by the military (mis)rule of my country, Nigeria, which came to a climax in the late 1990s. It was also a means of negotiating my artistic advancement under a traumatized economic climate,” he says. He later realized that the miniatures were also a strategy to engage even a casual viewer in a more intimate experience of his work.

To x-ray this retrospective, one needed to look at its categories, starting with the Landscapes of the Soul series, which also served as the exhibition’s general title. The works in this series are collections refered to in the catalogue as “self-contained yet related miniature images,” mainly in watercolors. Its main subject, the old city of Zaria, was painted from many perspectives, like quick shots of a fast-vanishing place. The centuries-old settlement shows the architectural heritage of the people’s earth. In many ways, says Buhari, “Zaria nostalgically reminds me of Akwaya, the land of my birth, a peaceful hamlet surrounded by freshwater rivers and hills, but now under existential threat. Zaria also reminds me of other lands where the environment needs remediation.” Under this theme, the following works are the artist’s offering to convey his messages: Erosion in the City (1995), Farmer’s World (1995), Anthills of Nsukka (2008), Journal of an Old City (2013).

Military rule brought about repression and depression, and was for many even life-threatening, still, for Buhari, that negative experience became a catalyst for his personal artistic evolution. He would shape sociopolitical commentaries through his work by extrapolating experiences that personally hurt him deeply. This was the background of what he calls “Landscapes of the Soul,” which are etched in his mind like frames of memory. They are recollections of places he visited, such as Lagos, Nsukka, Kansas, Gorée Island, and Dakar.

Jerry Buhari, Politicians Daughter with many Jewelries, 2021. Sand, Coffe and pen on paper. 37x55cm. Courtesy the artist.

Buhari’s images express his fascination for the environment and the happenings around him; he believes that the earth is a silent witness bearing profound messages of enduring importance. For him, it is the source which nurtures and nourishes. “It speaks to and reminds us of the connection we share,” he says. For over thirty years, Buhari has viewed the earth as a subject, a motif, and a medium laden with meaning. “In my interaction with the earth, when I paint, I feel the texture and scent of home,” he says. “When I encounter residues and pollutants, I am reminded of a lost paradise.” Works that reflect this sentiment are: The Couple (2016), Dressed (2015), Politician’s daughter with many pieces of jewellery (2021–22).

Jerry Buhari, Landscpaes, Images and Symbols, 2005. Water colour on paper. 21x29cm. Courtesy the artist.

In 2016, Buhari led a monoprint workshop sponsored by Yemaja Gallery in Lagos. The resulting works have gone through a deep conceptual infusion, leading to their articulation as a body of work under the Mixed Media title. Buhari’s concerns about society, such as neglect and inequality, are expressed in the Princess in a garden II (2016-2017), Great expectation: Embryo of a prince (2016), Women in blue hijab (2016), Silent mothers and children (1998-2020), and Warm Spillage (2016) His concerns for the environment are suggested in works represented in darker, more exuberant colors. Virtuositically, he utilizes the immediacy offered by the monoprint technique to achieve intricate and vibrant colors that seem to capture formal and visual essences.

The Black and White Series is Buhari’s most recent studio experiment. The works are painted with rich monochrome, with variegated strokes and assortments of lines. Their range of mark-making techniques indicate the artist at his most creative. The multilayered textures reflect Nigeria’s frequently somber political history and its effects on Nigerians. In the catalogue, the exhibition’s curator Favour Ritaro writes: “We have been through a series of events and experiences that call for self-reflection and re-evaluation.”

Framed by his own experiences and connection to nature, Jerry Buhari’s art gives us a powerful sense of humanity. He investigates the complexities of life and the playfulness of shapes and colors simultaneously. He intends to continue exploring the human relationship with the

earth, and the effects people’s actions have on themselves and the environment Landscapes of the Soul showed at Kó Art Space Lagos from 20 September to 11 October 2022.

Agwu Enekwachi is a visual artist and culture writer. He lives in Abuja, Nigeria.

FEMALE PIONEERS

Find an extraordinary, sometimes disconcerting selection of books linked to colonialism in our walk-in bookcase

More Editorial