C& talks to Edwin Cameron, judge, and Albie Sachs, human rights activist, about the Constitutional Court Art Collection of South Africa.

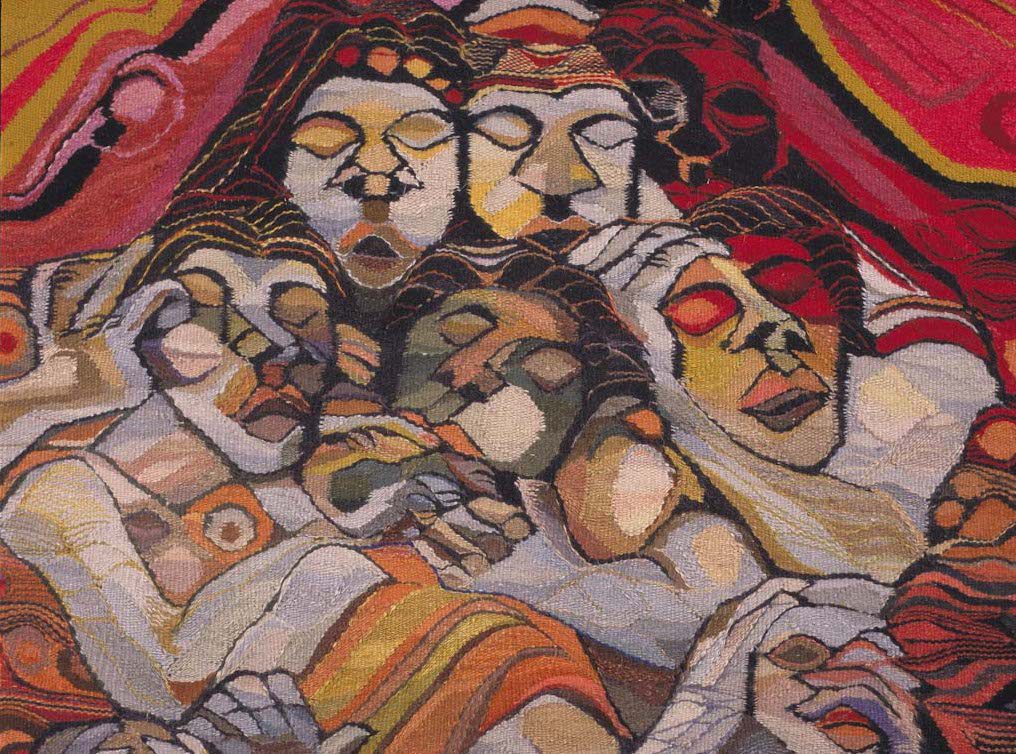

Joseph Ndlovu, Humanity, 1994

At the entrance to the Constitutional Court of South Africa, in central Johannesburg, stands a sculpture of a large man yoked to a cart. His burden is a human one: a man and woman who themselves are seated on the back of a fourth figure kneeling on the cart. At first glance, the sculpture resonates with the history of servitude that marked the dehumanising institution of apartheid. On closer reflection, the sculpture reveals a more complex message. Artist Dumile Feni did not create any racial differentiation between the four figures, and the man drawing the cart is the only figure who is large and strong enough to accomplish this task. The title of the work is History, and the four figures carry each other in a way that reflects the dependence, the interconnectedness and the tension that have always characterised human relationships.

Dumile Feni. “History” 2003, bronze. Photo by Akona Kenqu

History is the first of many artworks that challenge a visitor to the Constitutional Court to reflect on South Africa’s tortured past and the country’s transition to a constitutional order. As the highest court in the country, the Constitutional Court protects and enhances the fundamental values of human dignity, equality and freedom of all people living within South Africa’s borders. The Constitutional Court Art Collection (CCAC) is both a living monument to the ideals on which South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution is based and a reminder of the work that remains.

CCAC has humble origins. In 1994, when the original eleven justices of the court were meeting in an office park in Johannesburg, Justices Albie Sachs and Yvonne Mokgoro were given $1,000 to decorate the courtroom. The justices did something far more valuable than brighten up the space; they spent the entire budget on commissioning artist Joseph Ndlovu to create a tapestry that represented the principles of humanity. Since that initial decision, the CCAC has grown to include donated works by over 400 artists, a collection that is now valued at over $5 million.

Guided by the leadership of CCAC’s art curator, Stacey Vorster, a visitor to the court today is confronted, inspired and challenged by this collection. Upon entering the court’s foyer through a massive set of wooden doors that were hand-carved with representations of the 27 rights enshrined in the constitution, a neon light installation by Thomas Mulcaire, which loudly proclaims “A luta continua” (the struggle continues). A series of urban griefscapes by Regi Bardavid presents the artist’s emotional struggle after her husband was killed during a botched robbery. A nude self-portrait by William Kentridge highlights and reverses the ways in which nudity has been used historically as a tool of dominance to objectify particularly black and female bodies.

Further down the gallery, a tattered dress made from plastic bin liners bears witness to the sacrifice of Phila Ndwandwe, a general in the armed branch of the African National Congress who was caught by members of the South African Defence Force while attempting to smuggle information out of the country. After being stripped naked and tortured for refusing to give up any information, Ndwandwe fashioned a makeshift set of underwear for herself out of a blue plastic trash bag. This act of defiance and humanity burned itself into the memory of one of her captors, who told the story of Ndwandwe’s detention and death at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Upon hearing the story, artist Judith Mason wanted to pay homage to the extraordinary acts of an ordinary woman caught up in apartheid’s brutal machinery. Mason’s work includes a poem written on the skirt of the dress: “Memorials to your courage are everywhere; they blow about in the streets and drift on the tide and cling to thorn-bushes. This dress is made from some of them.”

These artworks transcend the decorative or commemorative. They create moments of empathy that translate abstract concepts like apartheid into intimate experiences of individual pain and resilience. This empathy is an essential component of the court’s jurisprudence, which is founded in human dignity. Art and justice are usually represented as dwelling in different domains: art is said to relate to the human heart, justice to human intelligence. Rationality is sometimes seen as inimical to art, and passion as hostile to justice. The Constitutional Court in South Africa shows how art and human rights overlap and reinforce each other. At the core of the Bill of Rights and of the artistic endeavour represented in the court is respect for human dignity. It is this that unites art and justice.

It is imperative that the CCAC maintain the pieces already on display and also expand its collection to include works of continued vitality. And yet domestic fundraising is all but impossible because the Court must appear impartial and cannot accept any money from South African donors or the South African government, who may appear as litigants before it. The CCAC, accordingly, suffers. As a result, the roof is leaking onto priceless pieces; important works lack labels and explanations that would enhance the understanding and experience of the court’s visitors; and tears of pigeon droppings run down Nelson Mandela’s cheeks in a depiction by Amos Miller. It is for these reasons that in October 2014, The Foundation for Society, Law and Art in South Africa officially launched its fundraising campaign at the offices of Hogan Lovells in Washington DC and New York. The main goal of this foundation is to establish an endowment for the purposes of protecting, maintaining and eventually expanding the court’s art collection.

The state of the collection mirrors the troubles faced by South Africa as a country. After a period of exuberance in the years following an astonishing transition to a legal order that protects the rights of all people, the hard and grinding work of maintaining a successful democracy has set in. The success of South Africa’s new constitution will be determined not only by the strength of the judgments coming from South Africa’s courts, but also by the efforts across all of the country’s civil society to promote respect for the human rights of its people.

CCAC symbolises the best aspirations of our democracy, of reconciliation, of justice, and of transformation… when we’re fighting for the artworks, we are also fighting for the underlying project of making a viable democracy in South Africa. To this end, the importance of the CCAC is not only to infuse the judgments of the court with empathy, but to provoke debate and reflection across a broader swathe of South African society. As the American jurist Learned Hand said: “I often wonder whether we do not rest our hopes too much upon constitutions, upon laws and upon courts. These are false hopes, believe me, these are false hopes. Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women, when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it, and no court can even do much to help it. While it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, and no court to save it.”

CCAC does not rest its hopes solely on the jurisprudence of the institution whose building it shares. It promotes the ideals of South Africa’s constitution in a way that both overlaps and is independent of the law through a series of enigmatic and essential messages. Memorials lie everywhere. The struggle continues. We carry each other. CCAC represents a history of intense passion, pain and redemption. And as it reflects on that history, it challenges and inspires a history that has yet to be written.

C&: What are the motivations behind the Constitutional Court Art Collection (CCAC) of South Africa?

Albie Sachs & Edwin Cameron: CCAC began when Justices Albie Sachs and Yvonne Mokgoro chose to use the Constitutional Court’s small decor budget of about $1,000 USD to commission a tapestry from Joseph Ndlovu. Titled Humanity, this tapestry is perhaps a wish for the future of a country, which has been so deeply divided by the trauma of its history. The artwork features several people huddling together. All of them have their eyes closed, unable to judge gender, race, or age, and in this way uniting them in their humanity.

In many ways this artwork is a departure from the Greco-Roman personification of Justice as a blindfolded goddess balancing the scales. Used as the symbol of the rule of law all over the world, Lady Justice seems to imply a universal concept of what is just. Her blindness too suggests impartiality, but perhaps when justice chooses to be blind, she’s not as welcoming to those seeking her most urgently. In Humanity, the mirrored action of people closing their eyes seems markedly different: a coming together of communities to consider justice through empathy and togetherness. It is a working concept of justice that is determined by a multiplicity of voices.

Similarly, the logo of the court, designed by artist Carolyn Parton, departs from the symbol of Lady Justice by featuring a group of 11 people gathered beneath a tree. The 11 people represent the 11 official languages in South Africa, which indicates how all citizens of the country are sheltered by the constitution and the rule of law. But, importantly, the figures are not merely sheltered: they actively hold up the branches of the tree.

CCAC has grown out of the purchase of Humanity to include over 400 pieces by artists from all over the world. As an expression of justice, human rights, and reconciliation, the installation of this art collection provides a multiplicity of voices to participate in the way we imagine the future of the country and, perhaps more importantly, engender empathy and unity. Most court buildings, if they have images in them at all, have pictures of dead white male judges. One day both of us will be dead white male judges. There is nothing wrong with that, but if those are the only images, they say that only men mattered and only whites mattered.

C&: Which artists have been selected, and how?

AS & EC: With the exception of Humanity, artists, patrons and galleries have generously donated all the artworks in CCAC. You could say the collection collected itself. While the common theme is a respect for human dignity, the collection is incredibly eclectic. It includes a large collection of early twentieth century beadwork from all over southern Africa, a number of significant pieces of resistance art from the 1970s and 80s, a three-headed dog made by the Handspring Puppet Company (famous for the theatre production War Horse), as well as a number of more contemporary pieces by artists like Marlene Dumas, Dumile Feni and William Kentridge. Artworks are selected for the ways in which they speak to concepts of justice, human rights and reconciliation, but also for the kinds of stories they tell about South African history and identity.

C&: Between 1994 and 2014, what have been major milestones for CCAC?

AS & EC: Over the last 20 years, tCCAC has developed into one of the most significant collections in South Africa. In some ways, the growth of the collection reflects the transitions, negotiations, and shared trauma of the last two decades. Paul Stopforth’s Freedom Dancer (1992), for instance, seems to capture the celebratory atmosphere of the 1994 elections that marked the end of apartheid. The events of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission are told through a number of pieces in the collection, including Judith Mason’s Blue Dress (1995), which tells the story of murdered activist Phlia Ndwandwe. The struggle against HIV is also reflected in many of the artworks in the collection, particularly in a series of poignant body maps made by HIV positive people, including pregnant mothers. What started as a collection intended to provide an emotional component to the rational practice of law has developed into a living monument to the founding principles of our constitution. In a more practical sense, the collection has also grown in a way that has exceeded its original intentions and as such needs support and careful management.

C&: What has been the response of lawyers, politicians, the art world and indeed ordinary citizens to the collection?

AS & EC: CCAC has secured a pivotal place in the public’s conception of art in South Africa. By corollary, the collection pivotally shapes the public’s view of the constitution and the rule of law. Thousands of visitors to the court each year enter the building through its magnificent spacious foyer, where the exhibition starts, and proceed down the court’s generous public corridor – 150 yards of steps, in a spacious, light, amply-proportioned gallery – where the most striking and memorable pieces are displayed. Counsel expresses their enthusiasm for the building. Poor people claiming their fundamental rights feel comfortable and acknowledged in it. Many of these are the schoolchildren, who come to the court in busloads every Saturday for the court’s public education and outreach programme run by law clerks and other volunteers.

The collection has also become internationally famous and has been visited by dignitaries from around the world including Barack Obama, then a Senator for Illinois. One prominent architect declared that the court achieved better than any other building in the world the Bauhaus dream of combining art, architecture and craft in a socially and artistically meaningful whole. In the foreword to Art and Justice, Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg remarked: “Imbued with the spirit of emancipated humanity, it is the most vibrant collection I have seen in any courthouse in the world.”

Public events at the court are held in the gallery, surrounded by the art of Kentridge, Dumas, Noria Mabasa and Marc Chagall. The Chagalls were donated by the artist’s granddaughters, Meret and Bella, as a mark of respect not only to the court’s human rights work, but to the public significance of the collection itself. The major structural addition to the court building since it opened in 2004 has been the Flame of Democracy, a perpetually burning fire cradled in one of the arches formed by the watchtowers of the prison on whose foundations the court is built. The flame at the entrance, and the art collection within: these are the visible and memorable markers of the court’s work to secure justice and the rule of law within a democratic non-racial South Africa.

C&: How is art connected to human rights and law? How can the arts bring more empathy and emotions into the field of law and politics? And, in a related vein, how does one avoid instrumentalizing the role and function of art?

AS & EC: There is an important historical linkage between the law and the arts. In some ways, the two share important similarities. At their best, art and law can each reflect the aspirations of humankind. Just as a constitutional charter might, an important work of art can provide an important marker of social identity. They are imprints of how a society views itself and also what it hopes to become.

The very distinct experience of South Africa on its road to freedom is embodied in both the terms of its constitution as well in the creative works that make up the collection. They are all concerned with the core principles of affirming human dignity and embracing the rich diversity of its people, which animate the new political order in our “rainbow nation”. For this nation, law and art can provide direction and inspiration as it continues to grapple with significant challenges relating to identity, resources and power during its third decade.

At the same time, though, art as an independent force can play a distinct role in society that often inures to the benefit of law. While law is often the product of institutional arrangements and group compromises, art is by contrast the instrument of the individual’s free expression. Art has the capacity to voice the truth that can speak to power even when few other venues are available. Through songs, in satire, or in the visual arts, art and artists have presented thoughtful insights and, at times, critique of the law and legal systems. South Africa’s deep well of art-based protest is on full display in this collection, reminding observers of all kinds just how consequential expression is in a free society. Lying beyond the strictures of formalism and rules, the power of art in this sense is its ability to prompt discussion and dialogue about law by celebrating the humanity of the oppressed and (often at the same time) by seeking the humanity in those who would deny justice.

For all of these reasons, society must always remember the importance of maintaining the space for art to flourish in society. To be sure, one must show due regard in a collection for balance in the effort to respect expressive freedoms. One person’s protest is another’s obscenity. But it is also true that where the aims of art become too entangled with the needs and demands of law, neither social pursuit can truly succeed. Thus, the social expectation must always lean toward advancing the principle of expressive freedom – perhaps even at the cost of respecting some creations that do not leave those in power resting easily.

C&: Can you elaborate on the Foundation for Society, Law and Art in South Africa and its fundraising campaign?

AS & EC: At present, CCAC is facing some important challenges that require sustained support and attention. While the collection has been housed in the court and has seen many visitors, the realities of time and the elements have taken their toll on many of the pieces. Due to unavoidable exposure, several pieces have experienced varying levels of wear and damage over time. While the collection has benefited from a small, talented curatorial staff that has ably addressed some of these concerns, a more robust system of maintenance is necessary to maintain this world-class collection over the long term. Further, the court’s institutional rules on conflicts limit its ability to accept financial contributions from sources in South Africa who might later present legal claims before the justices.

To address these challenges, the foundation was founded to develop a strategy for a long-term investment in the life of the collection. The group is an assembly of individuals whose respect and support for South Africa and CCAC come from their vantage points as former law clerks, litigators and businessmen. The goal of the foundation is to establish a sustaining endowment to fund curatorial services to maintain the collection; additionally, the foundation has a long-range ambition to use this fund to expand the reach of CCAC by organizing educational programmes and exhibition tours. Overall, the goal of the foundation is to help showcase the creative genius of the contributing artists and to present the themes of art and justice to a worldwide audience.

C&: Do you collaborate with other projects around the world that also work at the intersection of art, law and human rights?

AS & EC: From our knowledge, this particular collection of art (as an independent holding of a working court focused on themes of justice and freedom) is unique worldwide. However, we also recognise that CCAC is one among many important collections that are part of a conversation about art and justice. We would hope that as this project to preserve and expand this collection continues to gather momentum, we can identify more related collections with whom we might collaborate in the future.

.

.

Edwin Cameron has been a judge in South Africa for the past 20 years and a justice in the Constitutional Court since 2009. He is the author of Witness to AIDS (2005) and Justice: A Personal Account (2014).

Albie Sachs is renowned human rights and anti-apartheid activist and justice of the South Africa Constitutional Court since 1994. He has published numerous books on human rights issues, as well as an art book titled Images of a Revolution: Mural Art in Mozambique (1983).

More Editorial