At Dak’Art, international artists show their vision of the continent and the global Diaspora. What began as a small festival is now Africa’s most important biennial.

Bili Bidjocka, Last Supper: “Do not take it, do not eat it, this is not my body…”, 2016. 13 public performances and installations which take place in different events and cities around the world. Dak’Art 2016 international exhibition, Installation view, Palais de Justice © C&

In order to understand Dak’Art you have to attend the official ceremony at Théâtre National Daniel Sorano on the morning of the opening day. The cordoned-off streets, traditional musicians wearing lavish dress, perfectly styled hostesses, and soldiers standing stiffly suggest a state ceremony. In the festival hall, high-ranking diplomats, politicians, business figures, and sponsors are sitting in the front rows. They are mainly Senegalese, but there are also Moroccans and Saudi Arabians. Their presence reflects the importance of this biennial. And it becomes clear that here in Dakar, the capital of Senegal, powerful contemporaries meet to celebrate their culture. Europe does not play a role. The international guests sit in the back rows. Flanked by officers and ministers, Senegalese President Macky Sall comes on to the stage. Everyone rises. Those who didn’t know it before know it now: This is not a European biennial visiting Africa; Dak’Art is a genuinely African event.

Fabrice Monteiro, (P)residant, This is not a Phoenix, 2016. Mixed media installation. Dak’Art 2016 international exhibition, Installation view, Palais de Justice © C&

And that’s probably what Léopold Sédar Senghor wanted. The first president of independent Senegal was a great patron of the arts. A revered poet himself, during his tenure (1960 – 1980) he allocated a third of the state budget to culture. Although those days are long gone, the Dakar Biennale was initiated in this spirit in 1989. The first edition in 1990 focused on literature. Then, in 1992, contemporary art was at the center. Bolstered by success and the express wishes of the Senegalese government, this emphasis was retained.

With Simon Njami as the artistic director, the 12th edition of Dak’Art aroused tremendous international interest from the very outset. A large team from MoMA came, as well as important curators, collectors, and art critics. Njami was the cofounder of the influential Paris-based art magazine Revue Noire, which focused on global art years ago. He has curated blockbuster shows including Africa Remix (2004 to 2007) and was the artistic director of the photography biennial in Bamako from 2001 to 2007. Last Year, he conceived the exhibition Xenopolis for the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle. The show was based on the premise that in the world’s capitals today everyone is a foreigner. The motto of his Dak’Art is La Cité dans le jour bleu – the City in the Blue daylight. The title is taken from one of President Senghor’s poems: “Your voice speaks to us of the Republic, saying we shall build the City in the Blue daylight: in the equality of fraternal peoples.” And Re-enchantments is the title of Njami’s main exhibition. He invited the participating artists to develop new strategies and aesthetics in order to “enchant” the African continent and the whole world. He is interested in the artists’ ability to initiate new forms of energy and creativity.

François-Xavier Gbré, I am African, 2016. Mixed media installation. Dak’Art 2016 international exhibition, Installation view, Palais de Justice © C&

A major biennial on the African continent does not only arouse great expectations, but also elicits cliché fears. Will all of the works arrive on time? Will the event begin on time? Will the artists be present? But then the gates of the main building of the biennial, the former Palais de Justice, open punctually to the minute; it is as though the impatient art circus is entering a long-concealed treasure chest. The vacant palace of justice, a modernist hall built in the late 1950s with high, slender columns, a greenish mosaic floor, and a light-flooded atrium with greenery, is one of the most spectacular places to show contemporary art. The initial concern that even the most striking or largest artworks wouldn’t be able to compete with the architecture is unfounded. Indeed, the opposite is true. Powerful works, such as the installation by the photographer Francois-Xavier Gbré, can shine, and weaker contributions suddenly take on an aura they definitely would not have had in a white cube. Gbré’s neon tubes scream out “I am African” – but in Chinese characters. On the floor are sheets of paper with words such as “work,” “concrete,” and “stop” written on them in French and Chinese. It is not difficult to understand what they address: China’s growing presence not only in Senegal but all over the continent. For example, the Chinese government just financed the new Museum of African Civilizations in Dakar to the tune of 2.2 million Euros.

Alongside many unknown young artists from Ghana, Martinique, and La Réunion, visitors can discover in rooms off of the main hall internationally established artists, including Theo Eshetu and the artist couple Mwangi Hutter. Njami already showed both of them at his Berlin show Xenopolis. Eshetu presents a work from 2006, Meditation Light, a fragmented, almost poetic reflection on his experiences in Ethiopia. On two screens running at the same time, Mwangi Hutter’s video Burning Desire To Be Touched (2015) is devoted to harmonious relationships and the physical act of touching, which leaves traces of color on the faces of both artists.

In his video The Bird Lady, in 9 layers of time, Kemang Wa Lehulere takes viewers on an archeological quest. Deutsche Bank’s “Artist of the Year” 2017 documented the rediscovery of wall drawings by Gladys Mgudlandlu. The autodidact, who died in 1979, was one of the first black women in South Africa who was able to present her works in an exhibition. She had painted artworks all over house, but after her death the new tenants simply painted over these pictures. Wa Lehulere’s video shows how the wall drawings are uncovered again, bringing to light an almost forgotten chapter of South African art history.

Kader Attia, the Endless Rhizomes of Revolution, 2016. Mixed media installation. Dak’Art 2016 international exhibition, Installation view, Palais de Justice © C&

In one of the large rooms Kader Attia is showing Intifada: The Endless Rhizomes of Revolution. As in his current show at the MMK in Frankfurt, metal trees on which slingshots hang as a symbol of Arab resistance stand very close to one another. You have to force your way through to get to the last section of the building. In this room, the Egyptian artist Youssef Limoud installed a miniature landscape consisting of dust and found objects in one of the former courtrooms. The work recalls the cardboard architectures of the Congolese sculptor Body Isek Kingelez and the “fun cities” of Fischli & Weiss. Although Limoud, who studied at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, had only a few hours to set up his work, he was subsequently awarded the Grand Prix Léopold Sédar Senghor for his urban development vision.

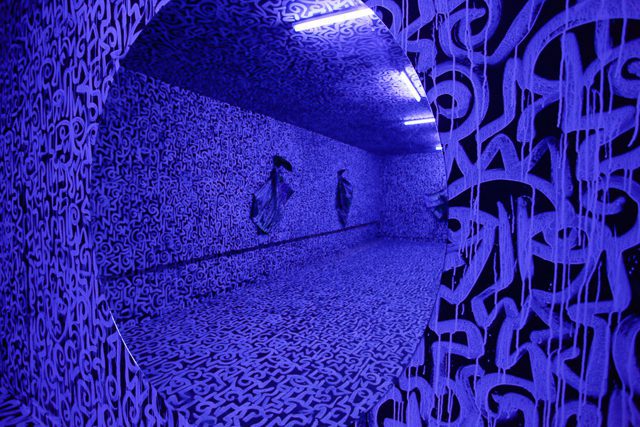

In his choice of the other venues for the biennial, Njami shows his great feel for the city. The main meeting place is La Gare Ferroviaire, a former railroad station with a bar and media lounge where symposia are held. On minimalist chairs, visitors can recuperate from the bustle of the biennial. Another location the curator revived is a small library. Conceived by President Senghor as a place of creativity, there is no longer much culture in this part of the city. But now the library houses the project At Work cofounded by Njami. A steadily growing group of artists, primarily young ones, is transforming a classic black Moleskine notebook into an artists’ book. In the intimate library visitors can slip on white gloves that have been put there and study the little books in peace. At Work is part of the so-called OFF program, nearly 300 events taking place outside of the official Biennale. The Raw Material Company is the site of one such event. The art center was founded by Koyo Kouoh, who recently opened the Ireland Biennale in Limerick while simultaneously curating the accompanying program of the art fair 1:54 in New York. She invited the Romanian artist and cartoonist Dan Perjovschi to Dakar. In his usual humorous manner, he covered the entire space with statements like “I am not Exotic. I am Exhausted.”

Dak’Art 2016, South South Connection: At the Musée Théodore Monod, the city’s largest exhibition hall, Senegalese dancers had rehearsed an Indian dance program. © C&

On the second opening day, Indian music blared on the square in front of Musée Théodore Monod, the city’s largest exhibition hall. At the invitation of the Indian guest curator Sumesh Sharma, Senegalese dancers had rehearsed an Indian dance program, complete with dazzling costumes, eyeliner, and perfect smiles. The performance was more than just a fusion of cultures. The much-discussed “south-south connection,” the link between regions outside of Western dominance, was almost unimaginably entertaining.

All that remains of another great performance are a couple of concrete blocks. Four young dancers had surrounded them with reduced, powerful movements, thus subtly reflecting the rampant construction work going on in Dakar. Half of the city consists of unfinished building shells – future offices, businesses, private homes. “Dakar is becoming grayer and grayer because the construction elements are built right at the location and the sand is simply left there,” says the young photographer Mame-Diarra Niang, who is showing her work at Gare Ferroviaire. “The countryside is so gray because there are construction sites everywhere and everyone wants to build higher and higher buildings. It’s as though the buildings are saying: I haven’t decided yet. Maybe I’ll grow even more, who knows?”

Victor Ehikhamenor, The Prayer Room, 2016. Mixed media installation. Dak’Art 2016 international exhibition, Installation view, Palais de Justice © C&

Youssef Limoud, Maqam, 2016. Mixed media installation. Dak’Art 2016 international exhibition, Installation view, Palais de Justice © C&

Thus, Simon Njami’s “Blue City” motto is alluded to again and again in various places and given myriad interpretations. Youssef Limoud called his miniature version of an imaginary Dakar constructed out of sand and found pieces maquam. The Arabic word denotes an environment in which people like to linger, but also a secret place at which they are blessed. Perhaps this 12th Dak’Art did not bless the art world, but it definitely enchanted it in many places.

.

12th Dak‘Art

Until June 2

Dakar, Senegal

.

This feature by Julia Grosse and Yvette Mutumba was first published in the Deutsche Bank ArtMag.

More Editorial