Our author Magnus Rosengarten met with Thomas J. Lax, one of the curators of "Unfinished Conversations: New Work from the Collection" currently on view at MoMA to talk about the challenges and opportunities of critical curatorial practices in major institutions.

John Akomfrah (British, born 1957) . The Unfinished Conversation. 2012. Three-channel video (color, sound). 45 min. The Contemporary Arts Council of the Museum of Modern Art, The Friends of Education of The Museum of Modern Art, and through the generosity of Bilge Ogut and Haro Cumbusyan, 2016. © 2017 John Akomfrah.

Magnus Rosengarten: Naming the exhibition Unfinished Conversations sets a tone. The title refers to Black British artist John Akomfrah’s first three-channel video installation from 2012. His work is inspired by the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall. Can you elaborate on this?

Thomas J. Lax: Unfinished Conversations is organized by five curators proposing a thesis and hypothesis about the museum’s collecting priorities across a variety of curatorial departments over the past decade. We knew we wanted to have singular artistic voices in the exhibition and to address some of the ideas in work we felt were most urgent to be on display. It became clear quickly that Akomfrah’s Unfinished helped us organize the exhibition. Unfinished is a magnum opus, and John Akomfrah is a critical reference for many of those working in the field of film and Black diasporic cultural practices. When considering the central tenets of postmodernism or the archival turn, Akomfrah has been a touchstone for almost four decades. In addition, Stuart Hall, who died a couple of years after the film was finished, became a key figure in the conceptualization of the show. He helped us reflect on the legacy of cultural studies today, on the expansion of the conversation in museums beyond the established tenets of art history, and on how one can do critical work within the context of an institution like MoMA.

John Akomfrah (British, born 1957) . The Unfinished Conversation. 2012. Three-channel video (color, sound). 45 min. The Contemporary Arts Council of the Museum of Modern Art, The Friends of Education of The Museum of Modern Art, and through the generosity of Bilge Ogut and Haro Cumbusyan, 2016. © 2017 John Akomfrah.

MR: How will this show influence future curatorial choices at MoMA?

TJL: The museum in the last several years has been organizing permanent collection shows that are more essayistic, less one view of the collection and instead a subjective, argument-driven slice. For example, Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980 (2015); Soldier, Spectre, Shaman: The Figure and the Second World War (2016); and Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction (2017), are also shows that, rather than universalizing what MoMA’s collection is, explore specific moments that needed critical reevaluation to re-pattern the singular narrative with which this institution is associated. Unfinished Conversations is part of this larger effort. It might be distinct in terms of thinking through the Black Atlantic or the influence of cultural Marxism on contemporary art practice. However, the effort to display the permanent collection as anything but permanent—as being in this moment and doing historical work that imagines this relationship to a future sense of possibility—reflects the museum’s work over the last several years.

MR: Could you say a bit more about the curating process? How did you guys discuss, choose, possibly argue?

TJL: Yes we did all of those things, and hopefully this process of negotiation and dialectical thinking helped us arrive at an associative thematic context where one artwork leads to the other. In a way, this allows the viewers to enter the exhibit and construct their own sense of meaning or associations. We tried to model the open-endedness of the conversation with specific points in it. There are definitely stakes in the ground but they can open up other interpretations and ways of decoding the work that is on view.

Kara Walker (American, born 1969). 40 Acres of Mules. 2015. Charcoal on three sheets of paper. Overall 105 × 216″ (264.2 × 548.7 cm, detail. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Candace King Weir, Agnes Gund, and Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine Farley, 2016. © 2017 Kara Walker

MR: How do you as a curator begin envisioning a show? What kind of audience did you have in mind for Unfinished Conversations?

TJL: When you make a show, you have to do two contradictory things. First, perceive your viewer, imagine her as your ideal interlocutor. For me, that is somebody who is curious, who perhaps also has some references in terms of art but is not going to know every figure or movement one cites; somebody who asks questions but is also given some signposts along the way. And this person might have a race, a gender, and be of a generation. This approach helps the show feel contingent, specific, and have a mode of address. But then, simultaneously, you have to be open to an uncertainty, to not knowing who will come across your show, especially at a place like MoMA with visitors from all over the world. And this sense of chance, of generosity and accessibility, is also key to inviting challenges and new ways of understanding the cultural contexts from which we are emerging.

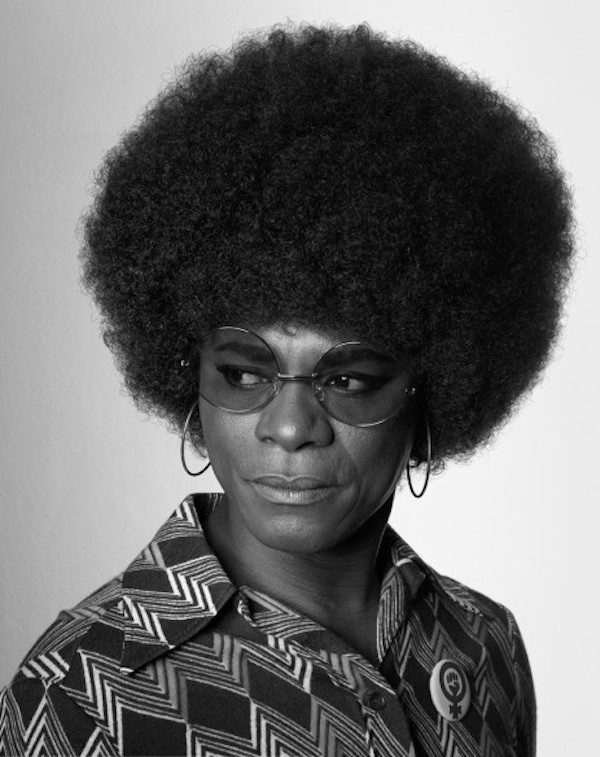

Samuel Fosso (French, born Cameroon 1962). Untitled from the series African Spirits. 2008. Gelatin silver print. 64 1/8 × 48 1/16″ (162.8 × 122 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man Fund, 2016. © 2017 Samuel Fosso.

MR: What do you think is the task for a young, informed and conscious curator in 2017?

TJL: The industry around working in museums is booming. In addition to the art-historical routes into this field, currently there are programs to study new “disciplines” like Museum Studies or Curatorial Studies, as well as various internship and fellowship programs to train aspiring young curators. But the political times in which we are living also demand that we admit that we often don’t totally know how to do what we are doing, despite our good training and disciplinary formations. When I say we, I mean those institutions that are invested in forms of civic engagement that have been disallowed even under the rubric of democracy. While we don’t have the answers, we do have historical forms of knowledge we can call upon. Relying on the questions people have asked prior to us is the best form of collectivity that we can try to create to be able to answer them now. We also need an openness to try things anew because clearly things don’t always work out. It’s an exploration, an experimentation, and for that negotiation of meaning, I am grateful to artists, and in particular to the fifteen artists that are in this show.

Magnus Rosengarten is a filmmaker, journalist and writer from Germany. He lives in New York City and currently works towards his M.A. in Performance Studies at NYU.

More Editorial