When Correspondence Reactivates History

07 February 2017

Magazine C&

7 min read

The recorded narrative as a medium of critical discourse is articulated in this project to question reality. Walter Benjamin stressed that in the construction of grand histories, written History is the narrative of the winners. But he added that being a historian does not mean knowing how things happened. In every period we have to …

The recorded narrative as a medium of critical discourse is articulated in this project to question reality. Walter Benjamin stressed that in the construction of grand histories, written History is the narrative of the winners. But he added that being a historian does not mean knowing how things happened. In every period we have to get away from the conformist approach that tries to glorify this history. By reviving the correspondence based on K7 audio recordings that circulated in families divided by labor migration, the artist is questioning the notion of territorial and cultural frontiers. For Badr El Hammami, reactivating the practice of K7 communication has been a way of circulating this history as plural or singular narratives.THABRATE speaks to us about forgotten memories and their past that can only be heard now, in the present.

Elsa Guily: Tell us about the story that led to the cassette that you rediscovered, and the correspondence method you are reviving with your artistic practice in the form of video installation, sound…

Badr El Hammami: The project is called THABRATE, which is the word for ‘letter’ in the Berber language, in the sense of correspondence, mail. The project began in 2010 and was inspired by a mode of corresponding that was used from the 1970s to the 1980s by Moroccan immigrant workers to France and their families who stayed in Morocco. In 1962, France encouraged labor migration of Moroccans as a “pretty cheap” solution to the labor shortage. Until then this had been restricted mainly to Algerians. But since political relations with Algeria were very tense after independence, France signed political and economic agreements with Morocco to encourage labor migration. K7 audio recordings were very widely used for communications at that time in Morocco. In fact, cassettes advertising the need for migrant workers in France were circulated to illiterate people in the villages. The majority of workers were unable to read, and telephones were not widely accessible in the villages. This means people had to rely on K7 recordings to communicate with their family. This appropriation of the technology of the time allowed them to record their daily life, sometimes as monologues or countryside sounds.

I discovered a cassette in my family archives in which I myself talk to my father. This cassette is a priceless treasure for me. My artist friend Fadma Kaddouri had the same experience, and we have decided to revive this method of correspondence with K7 with the aim of ‘re-enchanting’ our histories in our lives today through this unique practice of communication and by leaving aside all the other communication technologies.

EG : Do these correspondences reveal a tension between audible and visible history?

BEH : The project questions us about the writing of history. The audible narratives tell us about the history of the Berber Diaspora and the evolution of its oral tradition that was affected by the modern technologies of the 20th century. This mode of correspondence is like an oral letter that would become a tradition of its own in the Berber culture’s modes of communication. I hope to make this audible history visible while investigating the problem of its erasure. I would like to create a kind of sound library with these cassettes to make their contents appreciated again in the collective memory. This sound memoir records a very spontaneous moment of life. In 2012, during my residence atL'Appartement 22 in Rabat, I went to a meeting of neighbors from my old village to recover and collect the K7s with the correspondences. But this concerns something on a level of intimacy that people don’t like sharing. The cassettes also revive a history of separation that may be very sensitive. A friend told me he would rather destroy them than listen to them and expose that period in the present.

.

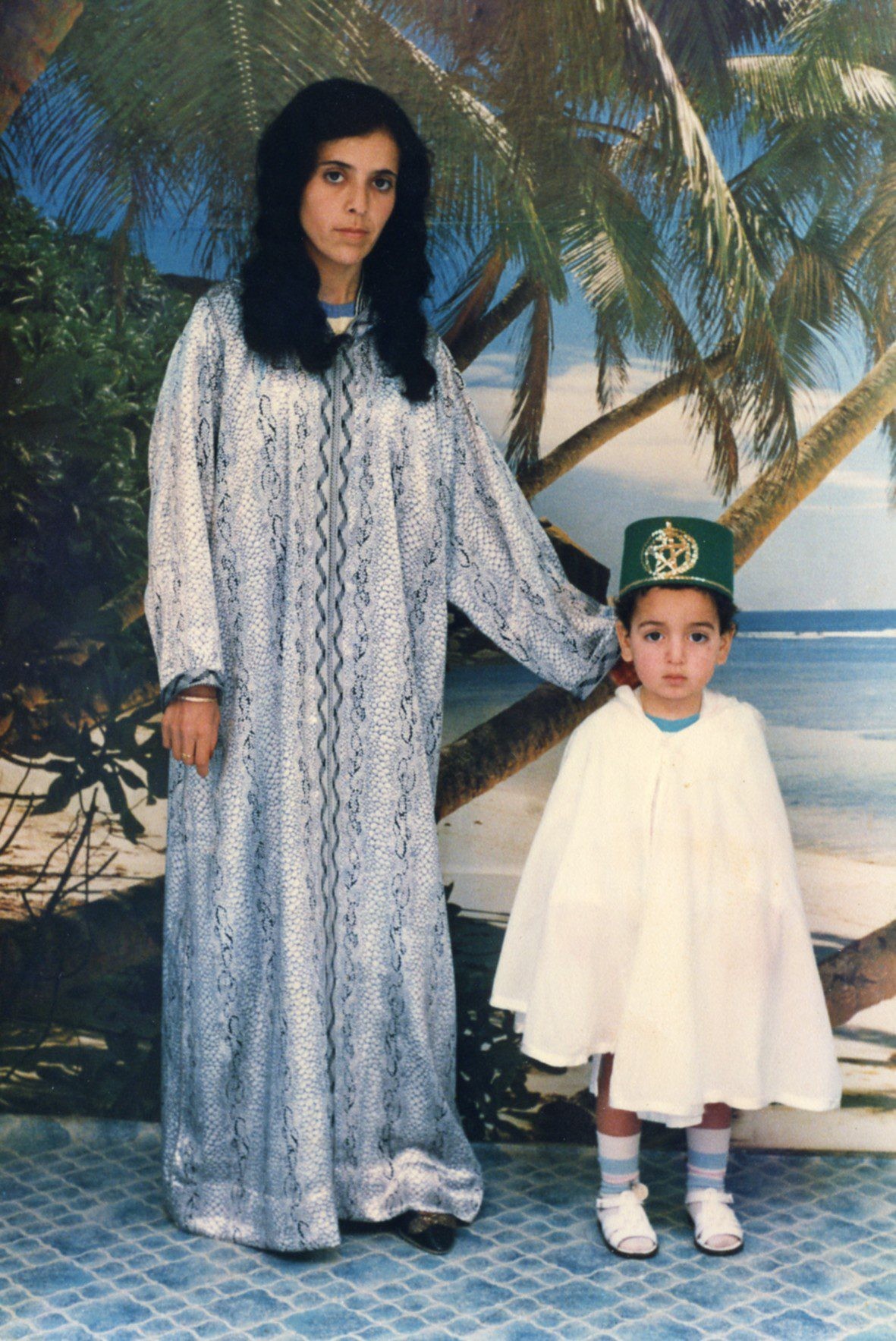

<figcaption> Badr El Hammami, Untitled, 2016. Photo. Courtesy of the artist

.

EG : How far does this reappropriation of the communication modes of that time allow people to rethink the wounds of postcolonial migration and make a collective link between the past and the present?

BEH : In the first place, the project evokes a wound, that of a collective memory that is in the process of disappearing. The aim of this project is to reactivate memories. The speakers on the cassettes never mention the time. The idea of inscription, of traces of history, was never conscious in practice, or at least not in the forefront. This was essentially about speaking with another person, activating the dynamic of the present, the shared moment. Oral transmission communicates history just as much as writing does. It is a very spontaneous transmission practice based on directly witnessing one’s own lived reality. The history of these correspondences has not been written and we are not trying to write it. Most of all we want to continue transmission from the word of the past toward the word of the present, a practice that belongs to Berber culture. This project also involves other elements related to its narratives, such as forgotten objects, bearers of history, and telling individuals’ stories. In the work on colonial history today there is the need to return to certain objects, to make them reappear. The question this raises is, how can we make these objects important again? To tackle this problem, the National Museum of the History of Immigration in Paris has created a special section for this type of object, called theGalerie des dons – the gallery of personal memorabilia. Anyone can bring an object and tell its story.

EG : Do you share the feeling that there is a lack of history about people who lived in the Diasporas?

BEH : The Berber Diaspora is spread all over the world, and yet we never hear it talked about. There is not a single center in France, for example, that collects its history. Our project explores this long history because these migration phenomena stretch across a vast region in the north of Morocco, the Rif, over a long, complex timespan. Very few people know that the first anti-colonial war was fought in the Rif. Abd el-Krim, who worked for the Spanish because, of course, the north of Morocco was a Spanish colony, understood that the French protectorate was a form of colonization. el-Krim was the first person to denounce the protectorate system, and was imprisoned. Traces are something that arouse fear. The idea of wiping out the traces of resistance to power persisted over the years, and even after colonization. We, the people of the Rif, have found ourselves excluded from national Moroccan identity. King Hassan spoke on television describing the Berbers of the north as ‘those people there’, suggesting that they were ‘not Berbers but barbarians.’

EG : How can we address this displacement of cultural identities in the history of the Berber Diaspora between Morocco and France? What is at stake today?

BEH : I think this audio material is a very important element in the history of Berber culture. The first time I presented this project in Morocco I had resonance from other people working in this area of communication practice. In fact, a network already exists in Morocco of people who are asking questions about archives in the making and who want to transform the national archives. But we have to be careful not to turn the cassettes into collectors’ objects, and we have to avoid succumbing to the fetishism of archival traces. The idea of this project is not to be restricted to a specific territory but to move around, particularly because this experience of correspondence in labor migration history in the 20th century existed on a global scale. This project is inspired by a local experience but the problems it raises are universal.

.

Elsa Guily is an art historian and an independent critic living in Berlin, specialized in contemporary readings of critical theory and the political challenges of representation.

from

Diaspora

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Bring Home your C& Collectors Box!

from

Elsa Guily

When Water Becomes a Screen

Earthworms and Caramels