“We have to test the premise that nations no longer matter.”

C&: It might sound a bit sappy, but do you believe in the power of an art exhibition as a transformative event able to appeal to what Willy Brandt once called our “Weltvernunft” or “world reason”? By us, we mean all the players involved from visitors to artists to curators. Okwui Enwezor: Well, I do not …

C&: It might sound a bit sappy, but do you believe in the power of an art exhibition as a transformative event able to appeal to what Willy Brandt once called our “Weltvernunft” or “world reason”? By us, we mean all the players involved from visitors to artists to curators.

Okwui Enwezor: Well, I do not know whether I want to ascribe that level of seriousness to exhibitions. But of course, exhibitions do speak to us, even though we might not register it immediately. There are some exhibitions that have meant an incredible amount to me, that were provocative on many levels, that I still struggle with and am still thinking about, and that are still intellectually enriching and culturally challenging. So exhibitions can do that. They can be transformative in an epistemological sense. But you should think more about what an exhibition could be.

In Venice, I am fundamentally interested in having an exhibition that is substantive, but without diminishing in any way the experience of the show. An exhibition is always fundamentally about experience: physically, visually, intellectually. So what I want to propose is that it is natural for an exhibition to have ambitions, and for the public to grasp what the propositions for an exhibition are. In the case of the Venice Biennale, we have to wait and see. For the Biennale, I have been really thinking mostly about the question of residue, the idea of the topography of the Giardini as a space of residue. Thinking about that notion of the residual, the accumulation of histories going back 120 years. What I really begin to see is the aspect of residue playing a very important role in regard to the Biennale’s notion of the Garden of Disorder. Residue will cast a shadow on objects that you are confronted with before you even go into any of the spaces of the exhibition, which is the Giardini with all the pavilions.

In 1907, the first national pavilion constructed in the Giardini was the Belgian Pavilion. And imagine in 1908, the year after, King Leopold was stripped of the Congo Free State. The Congo was the first global scandal of the twentieth century. And remember that in 1909, when the British pavilion was constructed, Great Britain was still known as the empire on which the sun never set. So it is about the residues of history and a general picture of the incredible instability in the world. Looking at the Biennale and the Giardini as a construct says a lot about the history of nations, their aspirations, the end of empires... so many things.

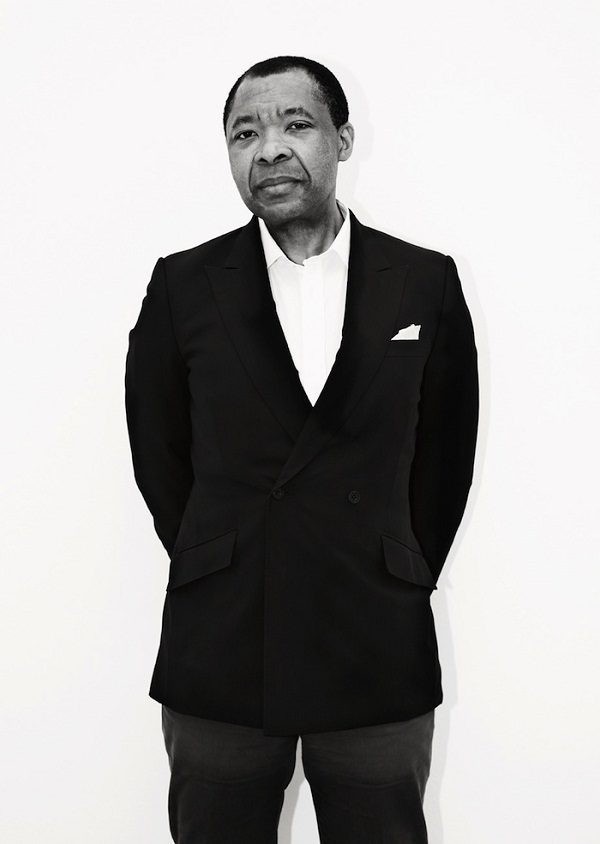

<figcaption> Okwui Enwezor. Copyright: Lydia Gorges

C&: What do you think of the proposition of artists deconstructing the idea of nations, for example by founding a lagos or Manchester Pavilion outside the giardini to underline how outdated this whole notion of nations is?

OE: I think we do have to test the premise that nations no longer matter. Because I don’t think it’s quite true. And I think it’s historically quite inaccurate. However, in the Giardini the history of nations is a fairly recent one. It’s a construct and it’s taking a shape that organizes the way in which we think about power relationships, territory, and politics. Nigeria is one example. Last year was the hundredth anniversary of the amalgamation of the Northern and Southern parts of the country that was then called Nigeria, a sheer invention of the British colonialists. But Nigeria, of course, was still celebrating the centenary of the formation of the nation. So they just have their narrative, they have their myths, they have their creation stories.

C&: everybody is talking about the economic and creative “south-south” connections now. the twenty-first century has been called the age of the global south. You have worked on that topic in the past. What do you think that “south-south” interest actually means? are we moving towards a more balanced art world? What opportunities, challenges, and risks does this development present in your view?

OE: Well, in my opinion it’s very hard to say. The way we are thinking about it is less territorial than geopolitical. The distance between Brazil and Nigeria is not very great, but it takes a long time to get to Nigeria from Brazil. So we have to deal with the sheer pragmatic question of moving from one location to another. It is therefore also about the distance that separates the South from the South. This question was broadened in 1954 at the Bandung conference, which was a kind of South-South alliance, and of course also in Belgrade in 1961, where the Non- Aligned Movement met. So these were moments of enlarging the projection of the South’s geopolitical ambitions. I think that we can return to that question today, but to what end? What does that propose, the South-South, the relationship of that axis? The South can also be the agglomeration of some aboriginal places. How does that reproduce any kind of access? Because it is all about access. It is about the powers of nomination and decision, and about who possesses and who processes those powers. I think this is what absolutely needs to be fought for: the geopolitical institution of alliances.

C&: Thanks to your work on projects such asdocumenta or NKA, to name just two, it must be a relief to you that now, with the upcoming Biennale, you are so beyond this whole talk about a truly global exhibition. there’s no need for you to point out that at least 50% of the artists included are non- Western, as you did that already around 15 years ago. the idea of the center has started to fade.

OE: It is not just me, I think it’s all of us. Our magazine NKA, for example, has never been about Africa as an identity but about the right to create a disciplinal space, a space for writers, thinkers, artists, and historians who reflect on the disciplinary development of contemporary African art. Speaking of the idea of the global exhibition, when I was appointed artistic director of documenta 11 in 1998, we were at the height of the so-called “Golden Age of Biennales.” Making a proposition to de-territorialize documenta was a proposal to de-provincialize it. When I look back and think about the early laments of trying to make that project happen, and the large quantity of serious skepticism, I remember that there was a critic for theFrankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung who assured us that it was going to be a disaster... And it was a difficult task because documenta belongs to Kassel, it is rooted there, it is a special place. But I think the agenda of the global in this sense was a disciplinary question and not just geographical and geopolitical.

And that is to say that within the discipline of art, there are artists who create from so many different impulses but they don’t all need to go to London to get these impulses. They, too, are challenged to present. To make an international exhibition in Africa, not an exhibition that plays with the expectations of what most people think is Africa, good artists need to take up that challenge. People tend to forget that my approach and my practice are disciplinary and that it is contemporary art. I have worked with contemporary artists of my generation from all over the world since the very beginning. But I think there is this narrative that Africa is not contemporary or international. Having said that, I think that our work to come will involve a disciplinary stage that we have to take up from an intellectual commitment towards contemporary African art.

.

Interview by Julia Grosse and Yvette Mutumba

Contemporary art

Naomi Beckwith Unveils Core Artistic Team for documenta 16

Venice Biennale 2026 Will Follow Late Koyo Kouoh's Vision

Kapwani Kiwanga Wins the 2025 Joan Miró Prize

Okwui Enwezor

Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present II

Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present