Connecting Europe and Africa by draining the Mediterranean Sea might sound like a ludicrous idea, yet it has been suggested multiple times by historical figures. In her ongoing project Operation Sunken Sea, Egyptian artist Heba Y. Amin explores such techno-dystopian proposals and gives performative speeches as their authoritarian initiators, drawing uncanny parallels to the present. Ahead of her performance at the Friendly Confrontations festival at Munich’s Kammerspiele, Will Furtado spoke to the artist to discuss what it’s like to play the role of dictator as a woman, and how we’ve become complicit in the pursuit of mad geoengineering mega-projects.

Heba Y. Amin, Operation Sunken Sea: Relocating the Mediterranean, Inaugural Speech, 2018. One channel video 18'21'' . Photo courtesy of the artist.

Contemporary And: What made you decide to personify authoritarian figures?

Heba Amin: Operation Sunken Sea started with my interest in geoengineering mega-projects, such as the various historical proposals to drain the Mediterranean Sea. I started investigating them through the archive of [early twentieth-century] German engineer Herman Sörgel, only to find that he was part of a long lineage of people who have put forth similar proposals. The earliest proposal I am working with so far is a mid-19th century French solution to deal with the “Arab problem” in North Africa by flooding the Sahara, detailed in Jules Vernes’ novel Invasion of the Sea (1905). In the 150 years since, draining, rerouting, or relocating the Mediterranean has also been contemplated by the Italian fascists and the US Central Intelligence Agency, among others. The idea has not been put to rest even today.

I was struck by what this represents – ideas to transform continents and the kind of violence that comes with them. I could not wrap my head around their enormity or grasp what the consequences might look like. So I chose to look at the characters behind these ideas to better understand where they come from. Who originates such ideas, and what could this mean in a contemporary context? I began looking at absurd movements that still exist, such as the Flat Earth Society, and the tools they use to garner support. I found my project to be a useful experiment in understanding the sociological and behavioral mechanisms behind politics today. It became a study of not just megalomania but of extremist ideologies. It helped me frame certain contemporary conditions and what it might feel like to be behind them.

C&: What does it feel like?

HA: It takes me out of my comfort zone. I take a tongue-in-cheek approach, of course, but at the same time try to convince myself by what I am doing. A performative approach allows me to dive into 150 years of techno-utopian ideology in a visceral way. What can be gained from proposing to move the Mediterranean Sea into the African continent, into the Qattara Depression? Through public speeches, I try to use a similar logic to my predecessors. I’ve studied their rhetoric, their gesturing, their aesthetics, their whole performance…

C&: Have you convinced yourself?

HA: I cannot gauge how convincing my version is, but the irony is that I am plagiarizing the words of others. All the content is very real. People have joked that I should be seeing a therapist while working on this project. That is probably not a bad idea. Maybe when I come to that realization it will mean that I’ve convinced myself.

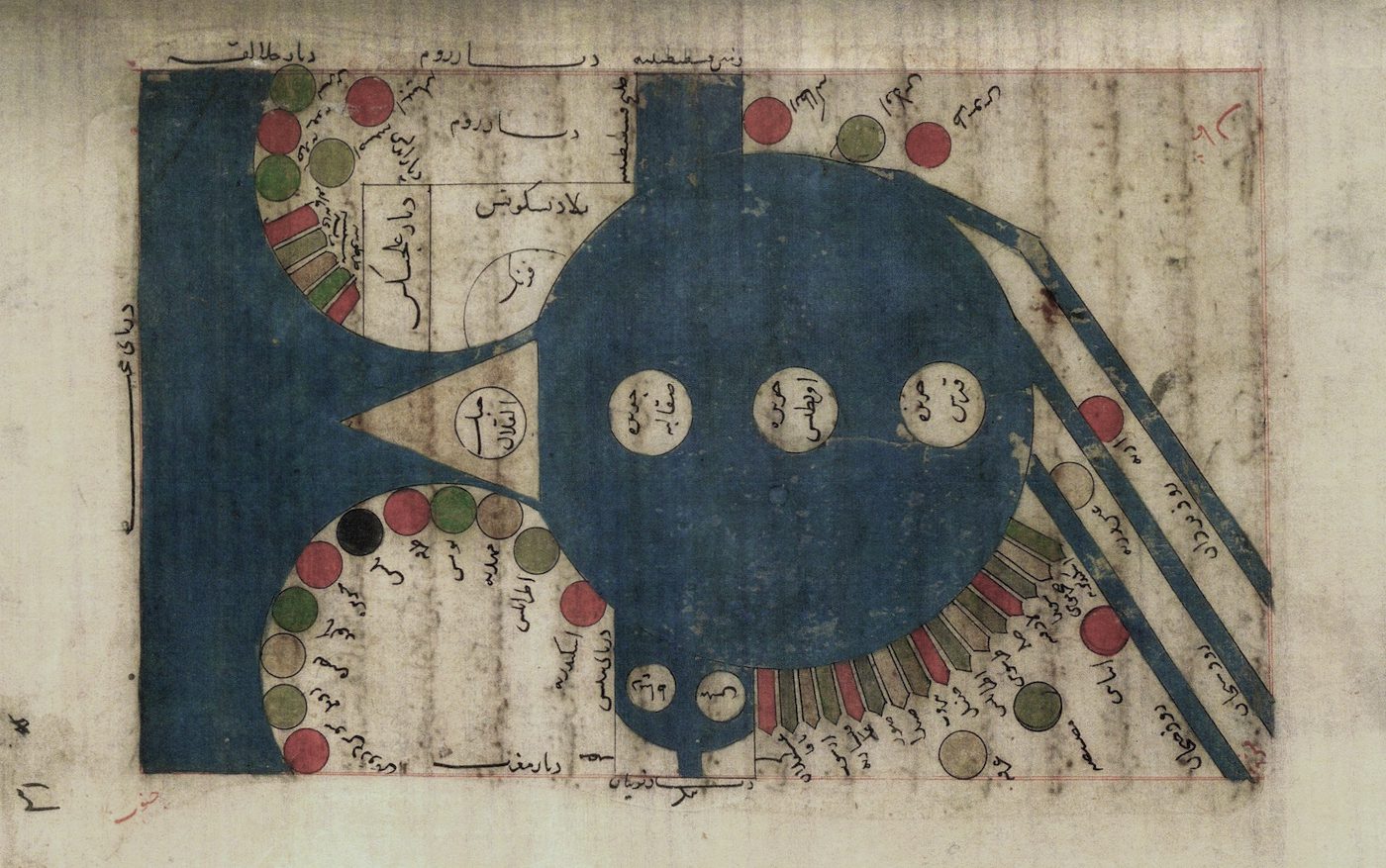

Persian geographer al-Istakhri’s 10th century map of the Mediterranean Sea (Balkhi School of Geographers)

C&: What specific parallels can you draw between older proposals and newer ones?

HA: I’m looking specifically at the rhetoric of contemporary projects, like Saudi Arabia’s multibillion-dollar techno-utopian city Neom, China’s New Silk Road project, and Turkey’s Istanbul Canal project. When I look at proposals from the mid-19th century and then at contemporary visions for techno-utopias, I see that our imagination has hardly shifted.

Continent-shifting projects are certainly not just a thing of the past, and they often come with an ego seeking to leave its mark on the world and ensure its place in history. One does not have to look far to find such megalomaniacs today. As well as to understand their performative tactics, part of the project is to belittle the narratives they want to be remembered by. I’d like to erase them from history as a form of resistance, or at the very least alter the way they are remembered.

I gave my first speech in Malta. According to Sörgel’s plan, Malta would be the first land bridge between Europe and Africa when the Mediterranean Sea begins to evaporate. None of the content of my speech is mine – bits and pieces are pulled from a wide range of 20th century speeches. I worked with an acting coach to see what I could get away with as a woman. How animated could I be? How aggressive could I be? How do I transform the words of speeches that are primarily presented by men?

I’m trying to bring attention to the ways in which these words no longer sound outrageous to us. Doing a project like this is about revealing the things we know but no longer notice, and are indeed complicit in. We urgently need to recalibrate.

Heba Y. Amin , The Master’s Tools I (restaging of Herman Soergel’s portrait), 2018. Archival B/W print, 86 x 110 cm. Courtesy of the artist

C&: As this is an ongoing project, what’s new in the Munich iteration?

HA: I’m uncovering so much interesting, and sometimes terrifying, material. The research behind this project is so rich and there are many elements that I am exploring. My performative speeches are just one small part of Operation Sunken Sea. The iteration in Munich will feature a new speech with new material. Munich is also a pretty significant location for my project, both because of its fascist history and because of the Herman Sörgel archive, which resides in the Deutsches Museum there. Many new elements make Munich the logical next place.

C&: It almost feels like any place would have some sort of history related to these ideas, unfortunately.

HA: Absolutely. You can find them everywhere. It’s also about how we connect the dots. As an artist, I am not interested in only engaging a historical archive but also presenting it in a way that helps us understand why it is still relevant. Megalomaniacs seem to have nailed down the mechanisms of propaganda. Perhaps there is something to be gleaned from that if we can use it against itself.

Heba Y. Amin will perform Operation Sunken Sea as part of Friendly Confrontations at Kammerspiele, Munich, Germany, on 18 January 2020

Heba Y. Amin’s Fruit from Saturn is at the Center for Persecuted Arts in Solingen, Germany, until 2 February 2020

Egyptian artist Heba Y. Amin grounds her work in extensive research that looks at the convergence of politics, technology, and architecture. Techno-utopian ideas, as manifest in characteristic machines of colonial soft power, are at the heart of Amin’s work. Starting from the idea that landscape is an expression of dominant political power – Heba Y. Amin looks for tactics of subversion and other techniques to undermine consolidated systems and flip historical narratives through a critical spatial practice.

Interview by Will Furtado.

More Editorial