Transitional moments and rituals

16 June 2013

Magazine C&

7 min read

A two-barred cross looms over two floors in the MCA Chicago’s main atrium. Lit from behind, the cross comprises individual cabinets that house a confusing variety of everyday objects. It elicits a peculiar feeling from me – the sneering aversion of an atheist raised to resist such symbolism, paired with professional interest in it …

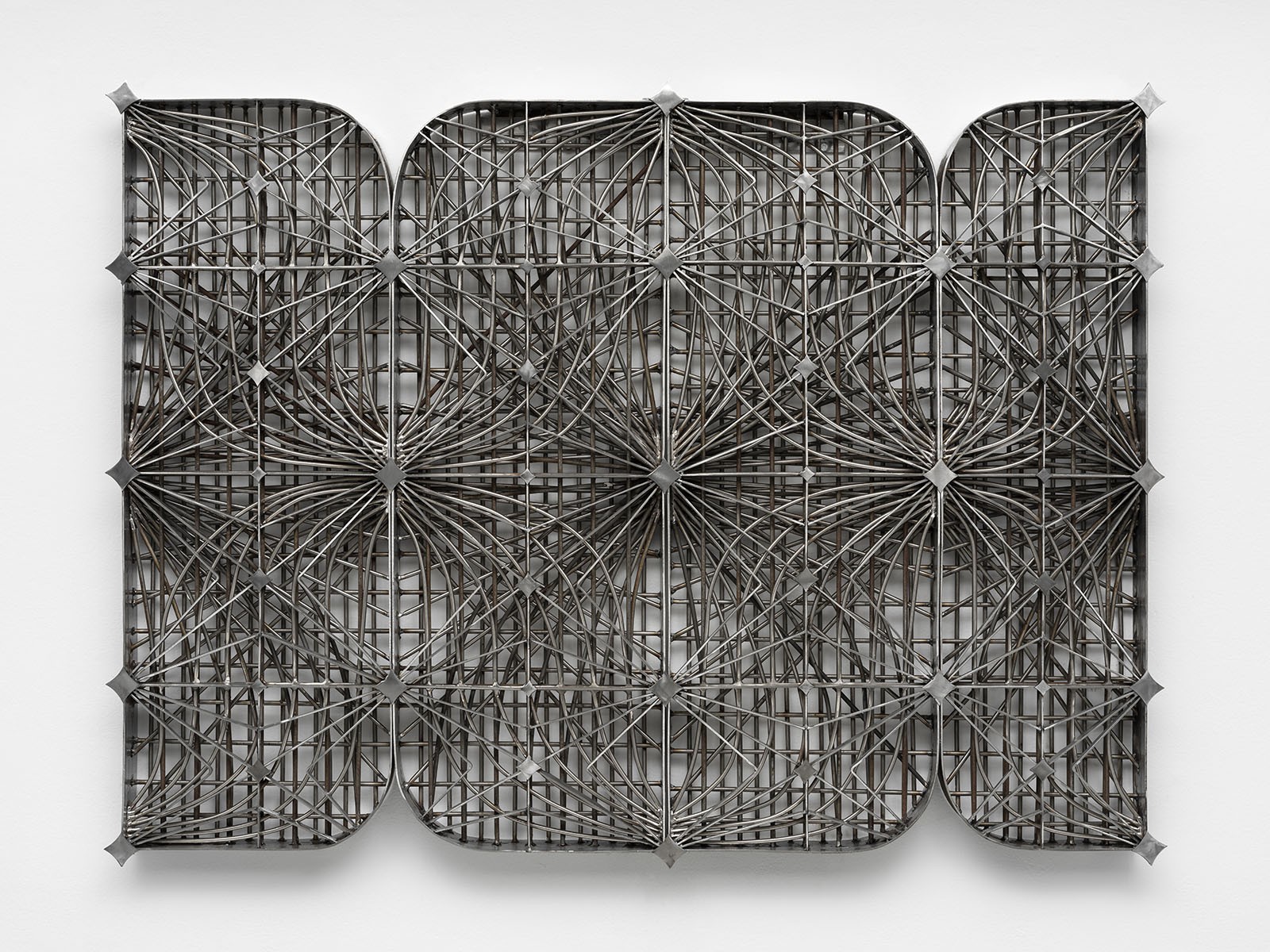

A two-barred cross looms over two floors in the MCA Chicago’s main atrium. Lit from behind, the cross comprises individual cabinets that house a confusing variety of everyday objects. It elicits a peculiar feeling from me – the sneering aversion of an atheist raised to resist such symbolism, paired with professional interest in it as the very basis of my discipline, as well as a stealthy fascination. Old wooden pews complete this highly suggestive set-up. They have been removed from a campus chapel of the University of Chicago in order to provide Muslim students with room to pray. I sit down on them and let Theaster Gates welcome me to church once again. Ritual is as central to the museum as civic institution as it is to Gates’ practice. As a kind of transitional threshold, the museum ritual serves as stage for the relations between the artist, the individual, the object, the market and histories. With his solo exhibition 13th Ballad, Theaster Gates adds a kind of postscript to his participation in documenta 13 in Kassel, Germany in 2012. A reprocessing and expansion that will most likely be strongest in three upcoming live performances that will take place in the atrium, and in which Gates will connect the several histories and places that are crucial to the two exhibitions. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=deCBuX7GYSo In the atrium’s cross, toothbrushes, cups and towels, pots and pans and other cooking utensils, hardware tools, neatly folded stacks of clothing, umbrellas left by unknown and absent owners form a kind of compendium reminiscent of Bachelard’s drawers. Visually juxtaposed with the white, slick and sober stonework of the museum architecture and its panoramic window, which opens up to the east over Lake Michigan, these stuffed wooden cabinets tell tales of intimate moments, slow-paced settings, provisional handiwork, manufactured goods and collectivity: spaces of yearning. But it is in the central, intimately lit, dark red box that contains the metal footrest of a shoeshine stand where these tales break open, fall apart and start to whisper, quietly, but strongly, about nostalgic notions of history, art market desires, race, class, power and labor. With these boxes, Gates employs the same design vocabulary that has become his trademark in dreamlike stage settings for his musical performances, as well as in art objects created over the past few years. For his documenta project, for example, he incorporated salvaged materials from a house at South Dorchester Avenue in Chicago into a temporal refurbishing of an old German Huguenot house, linking the two buildings for the days of the documenta, combining old and new materials and histories. Video projections of 12 soul and gospel ballads Gates recorded in Chicago with his group, The Black Monks of Mississippi, as well as ongoing live performances of musicians living in the coopted space, filled it with sounds that generated a surreal atmosphere, with the house’s old wooden planks bending and squeaking under every step, amplifying a sensation of teetering in and out of time and place, making one wonder whether this is real or merely a stage setting. A feeling that travelled well to Germany from Gates' Dorchester Projects in Chicago, where a simple effort to renovate a space for a studio a few years ago turned into an ongoing microtopia for the reuse of abandoned spaces, an artistic reworking of found materials and archives, experimental activation of these spaces through community and music, and the creation of a very specific economy of value. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwGqhqml87o The renewed interest in performance art of the past 15 years, parallel to an explosion of social practice and an engagement with place is especially compelling in Gates’ aestheticized and often nostalgic combinations that are additionally charged with black history and music, rendering them irresistible. But unlike similar projects, he not only makes visible and promises, he also delivers something to take home with you, if you can afford it. Long after the taste of exquisite soul food has vanished from your tongue, and the smell of used books, moldy houses paired with new wood and paint, as well as the ‘sounds of blackness’ are merely a distant memory, there are his “loaded, racialised, enigmatic, fetishistic, seductive objects, for sale.”[1] But despite their high popularity with private collectors and American museums, it is his performances that most evidently suggest the deep eruption that black culture poses to white traditions, and which can hardly be matched by Gates’ material-based practice – as loaded as it might be. Thus, it is not the confusing and callow presentation of a documentary film, video projections and dispersed objects in the 4th floor galleries of the MCA that can stand up as a resumption of examinations started in Kassel, but the still-to-come live performances which will take place in the atrium under the cross. On this stage, Gates and his ensemble as well as other collaborators will attempt to fuse music from the 1836 grand opera "Les Huguenots," written by German composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, with sounds inspired by the father of modern Chicago blues, Muddy Waters. While the opera tells a story of religious persecution and displacement in Europe, Chicago blues is the most obvious temporal and spatial transitional marker between rural black life in the South as the cradle of Mississippi Delta blues, and the industrial North, destination for millions of African-Americans during the Great Migration. The announcement of the performances refers to Meyerbeer’s neglected recognition as one of the prime opera composers, which was partly due to Richard Wagner's anti-Semitic campaign against his former mentor. But maybe more relevant to this set of freely associated relations is Meyerbeer’s father, a major sugar refiner in Prussia, who actively participated in the economies of slavery, and the inverted standing of the Huguenots in the US. Having been pursued in Europe, some of the religious refugees, who were imbued with a strong Calvinist work ethic, became notable plantation owners and slaveholders in the New World. Grand opera in a pentatonic scale. Gates is aware that positions shift with a change of place, and he is intrinsically interested in the span between these positions and how they can be put to work. Transitional moments are realized in performances and in rituals. Gates mobilizes labor as the overall metaphor of the exhibitions in Kassel and Chicago, as well as of his practice in general: speculating and strategically entangling histories of persecution, migration, race, violence, religion, labor, geography, economies and music throughout the Black Atlantic. Music as ritual, as intellectual process, as transformative moment for space, as activation of certain objects, as a feeling of being in the moment. Kathleen Reinhardt is a critic, curator and doctorial candidate based in Berlin. She is co-founder of the translation collective textual bikini. Currently, she is writing her thesis on socially-engaged and performance art in the realm of post-blackness at the Art of Africa department of the FU Berlin. Theaster Gates: 13th Ballad,Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, May 18 – October 6, 2013. Upcoming Performance at the MCA Chicago: Muddied Pentatonic with Believers and Blocks: June 30, 3:30 pm Migration Stories: August 11, 3:30 pm Church in Five Acts: September 22, 3:30 pm [1] Theaster Gates. Clay in My Veins and Other Thoughts. Lecture performance at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, 31 March 2011, available athttp://vimeo.com/23493473

Read more from

Feature

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Read more from

Performance art

Jesús Hilário-Reyes: Dissolving Notions of Group and Individual

A Biennial that relates sound to space and bodies