Trans-African Clarity

17 February 2016

Magazine C&

7 min read

January is an obvious but also tricky month to start up something new. Everybody feels overwhelmed by the beginning of the new year and is figuring out how to go about it. Yet The Trans-African launched its first issue on January 15 and did so in a clear-headed and focused way of mind. The online …

January is an obvious but also tricky month to start up something new. Everybody feels overwhelmed by the beginning of the new year and is figuring out how to go about it. Yet The Trans-African launched its first issue on January 15 and did so in a clear-headed and focused way of mind. The online magazine is dedicated to reflections on African art and visual culture and will feature independent African art writers. It’s a publication initiative byInvisible Border’s Trans-African Project, a non-profit organization founded by Emeka Okereke to patch “numerous gaps and misconceptions posed by frontiers within the 54 countries of Africa through art and photography.” The first issue features essays by the three editors Emmanuel Iduma, Ndinda Kioko, and Moses Serubiri. The tone that they set is a promising one: critical, which is refreshing in a mainstream art journal world. Furthermore, critical thinking finds its form in literature, truly honoring the art of art writing. For C& I talked to Emmanuel Iduma, Ndinda Kioko, and Moses Serubiri about the new platform, its background, presence and future.

An Paenhuysen: How did the idea for The Trans-African come about? Have you collaborated before?

Emmanuel Iduma: It’s always been a question of the conceptual—and political—framework with which we operate in Invisible Borders. The Trans-African was based on our interest in supporting independent art writing by African thinkers, those who work mainly outside the academic institutions, in the mainstream. I had admired the work of Moses and Ndinda. Once we settled for the current framework (having a select group of writers maintain monthly/yearlong columns in the journal), they were ready choices.

AP: In your journal’s statement it says that The Trans-African stands for clarity in writing and a clarity of ideas. Could you tell us a little more about this desire to be clear? Couldn’t one say that some writing, like poetry, gains from its opacity?

EI: We’re writing about images, and we live in a world with an inescapable surfeit of images. These two premises, for me, require writing that aims to get closer and closer to visual phenomena. Hence intimacy. But there’s also a sense of clarity as urgency—the ideas that might be lost to the world when the writer isn’t clear about the stakes of the matter. I say “intimacy” and “urgency” to establish that this isn’t primarily a matter of style or belletrism. While we aim to make our sentences clean as bone, the stakes are higher than that, and the territory certainly larger—charged, political, and historical.

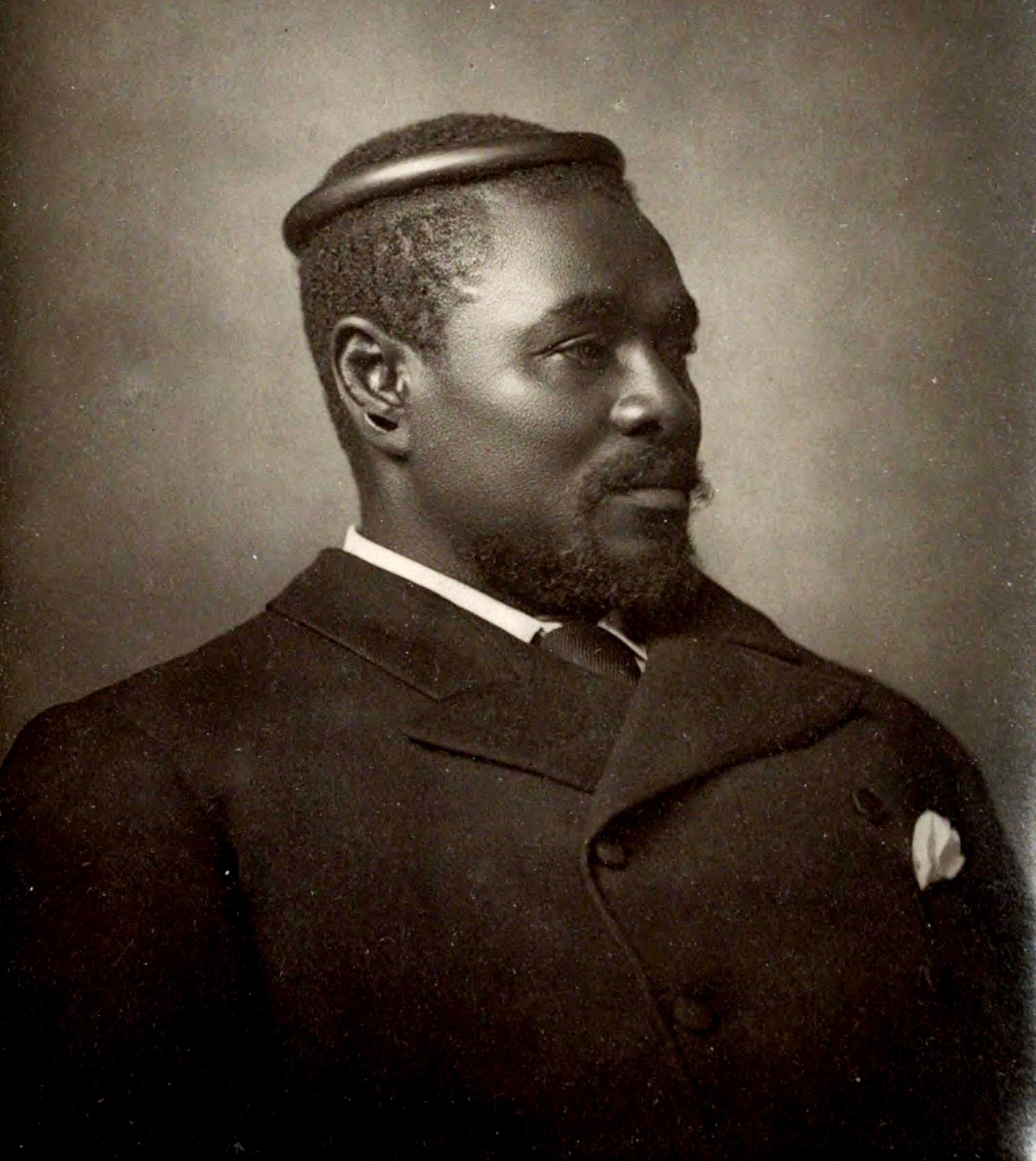

<figcaption> Cetshwayo kaMpande - Zulu King

AP: The archival image seems to be central to your first issue – yet there’s also an interest in what is missing from that archive, or how, as it is very much defined by colonialism, it can be re-imagined in the present. Will the archive be a central focus of the publication, and what is, for you, the benefit of looking back?

EI: I was surprised that when we shared the initial drafts for the first issue we were all addressing archives. But I see how that’s inevitable. We were born in post-colonies; we are products of sin, so to speak. How do we address that? I have become interested in the archives that I cannot access. I mean this literally and figuratively. I’d like to browse all the issues of West African Pilot, Nigeria’s premier newspaper, but I don’t know if or where they can be found. One way to make sense of this inaccessibility is through an investment in recovering lost histories, recuperating and retelling them, turning fact into fable—making history matter for who we are in the present, for who we will become in the future. So the benefit of looking back, simply, to quote Amiri Baraka, is to ensure that the future is not born dead, as a corpse.

Moses Serubiri: I am interested in what Gabi Ngcobo describes as a dilemma of absence. I am also interested in her follow-up questions: Whose dilemma is it? Who is responsible for this absence? I reflect on these questions very much, as they shape my relation to writing about images.

AP: How do you think that writing, texts, can change the way we look at things, the politics of seeing? Emmanuel, in your essay you claim that “language is always superfluous in relation to images.”

EI:The first thing I learnt about art writing is that you could write around images, or write into them. The latter is a project of revelation. On one hand you have scholarship, the rigor of coming to know, especially if you have to do research to understand the context in which the image was produced. That’s quite important; a critic has to be as intelligent as possible. However, beyond intellectual exercises, I always ask myself, where am I, and who am I, in relation to this image? Once I ask that in the course of my writing, I discover my prejudices. My writing in response becomes fluid and superfluous, making several detours. There’s that line from an Audre Lorde poem: “However the image enters, its force remains within my eyes.” That’s where I write from.

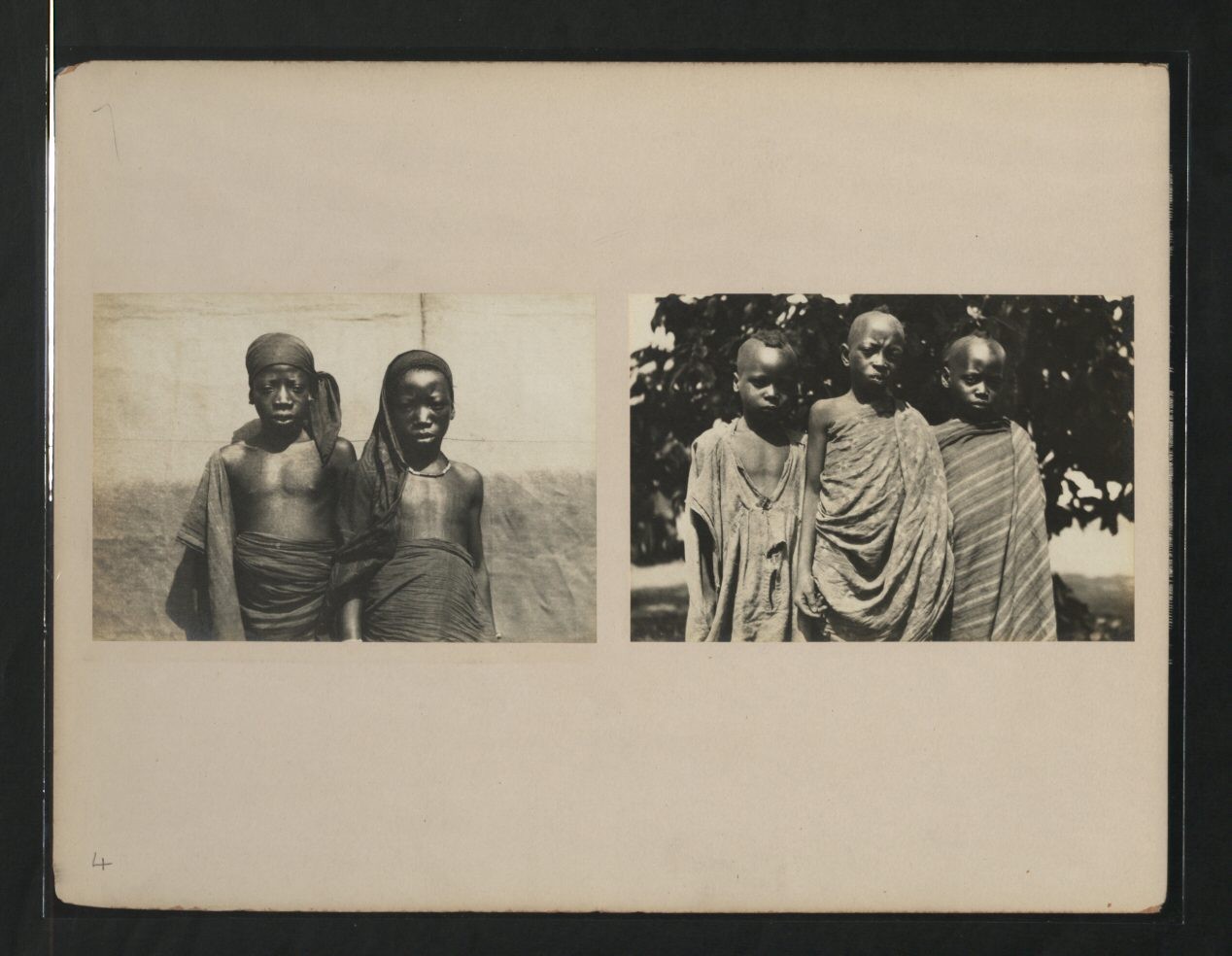

<figcaption> Kamberi girls and boys. Nigeria. 1920s.

AP: There is a personal voice in your writing, even memories are being told, like in your essay, Ndinda. I would say that the essays read like stories. Is this personal positioning something that The Trans-African stands for?

Ndinda Kioko: I find myself obsessed with this idea of expanding the space of the archive and pushing the personal to the center of my remembering. There is something beyond this personal, something beyond the naivety of the images on my father’s wall and memories of my grandmother’s stories. I want to look at the archive as one that is expansive, present in the everyday. I think I am playing around with the idea of how museum walls are also some kind of forgetting.

AP: In your essays you all seem concerned with expanding the photographic image, even opening it up to other senses than seeing, as you did, Moses, by connecting it to sound – “their tongues augmented that sound to reflect a blackness” – or you, Ndinda, to the tactile, the khanga. Would you say that by doing this, you try not only to understand the image, but to feel?

MS: Yes. In writing about the sound in the image I wanted to feel what it was like to be there. Luckily, the phonetics of 1885 are with us in African-Christian names. Faith changed to Faisi. Paul to Paulo. This sonic space is open for interpretation, and I'm excited about what it reveals about the image.

NK: All these things are present in each other. My darling friend Okwiri Oduor in an interview with Saraba Magazine says that “all art, not just writing, is incestuous. Painting begets dance begets sculpture, and all of it is poetry.” There is music in seeing. The reverse is also true.

AP: The Trans-African is published on a monthly basis. Contributors commit to write short essays each month for a calendar year. Did you opt for this set-up so that there’s a certain consistency?

EI: Yes, consistency. I believe in what the process of writing does to a writer’s intelligence. After 12 essays in one year, you are likely to confront your convictions, and understand better how your knowledge is organized.

An Paenhuysen works as a freelance curator, art critic and educator living in Berlin. She is a fervent art blogger and teaches art criticism online at Node Center for Curatorial Studies.

from

Announcement

Nnena Kalu wins Turner Prize 2025

Coming Soon: APRIA Journal Issue #7 — Exhaustion

Introducing the C& Cyclopedia

from

Art criticism

Darling, this is Switzerland

Unheard Voices: Arts and Culture Journalism in Nigeria