"This work tells a story of African hybridity."

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work? Ato Malinda: I had read portions of each section during my undergraduate years, so I was familiar with the text. I re-read some of it (but not …

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work?

Ato Malinda: I had read portions of each section during my undergraduate years, so I was familiar with the text. I re-read some of it (but not all), whilst preparing for the exhibition.

.

MMK/C&: In its merging of Christian beliefs and moral values as well as classical pagan topics, the “Divine Comedy” represents a deeply-rooted Eurocentric concept of society, values and culture. The exhibition aims at dismantling the European prerogative of interpretation and looking at it from a new angle. To what extent do you think this approach can lead to the Eurocentric interpretational sovereignty being generally put into question?

AM: I'm not sure that I perceive the exhibition's intentions as highlighting the hegemony of Europe. It is my understanding that Simon Njami wanted to align African art to the metaphor of Dante's poem. That is not to say that the context in which the exhibition is being presented does not show awareness of Eurocentricity and the post-colony. In fact, this exhibition for me was about veering away from the obvious contexts African artists are continuously situated in, and to truly talk about (the experience of) art and poetry.

.

MMK/C&: In European-North-American art history, the “Divine Comedy” has been interpreted by numerous artists (such as Botticelli, Delacroix, Blake, Rodin, Dalí or Robert Rauschenberg) – what role did this play for you in respect to your engagement with the topic?

AM: Of course I was aware of the significance of the Comedy, but I did not look at other artists' interpretations.

MMK/C&: How do religion and ethics feature in your artistic practice? And consequently, what do the terms heaven/hell/purgatory mean to you personally?

AM: I am very interested in African paganism. I find pre-colonial worship extremely gripping and appropriate. The terms heaven, hell and purgatory refer to monotheistic worship that I find limiting. Of course, this is speaking personally, as one can never speak for another on such topics.

.

MMK/C&: The over 50 art pieces in the exhibition are assigned to the areas heaven, hell and purgatory. What realm of the afterlife does your work belong in? How did this allocation come about?

AM: My work belongs in purgatory. I feel that I sit well in purgatory. I never claim to have any definitive answers and I feel my life and my work is about finding space to accept the uncertainty of life. The work I submitted for this exhibition tells a story of African hybridity; an African identity that is influenced by Asia and Europe; an African identity that defies authenticity.

.

MMK/C&: What is the work exhibited at the MMK about?

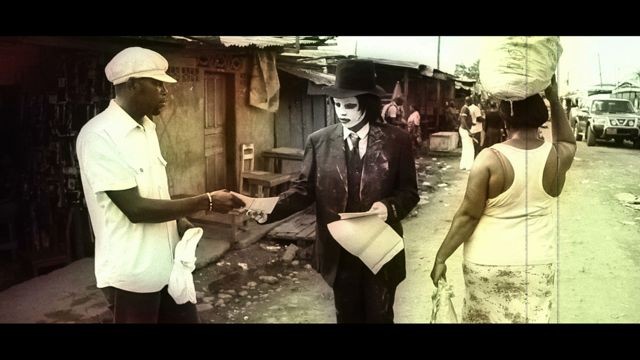

AM: As I began above, the work is about 21st century Africa. It tells a story of a pagan belief that was influenced by the migration of colonialism. The video is about Mami Wata, an ancient African water spirit worshipped by Africans long before the arrival of Europeans but whichcame into recorded history in the 15th century. It was recorded that when they first sighted European ships, Africans associated water spirits with the Europeans. During colonialism, in the 1880s, a famous German hunter, Breitwieser, brought back a wife from Southeast Asia to Germany. Under the stage name “Maladamatjaute”, Breitwieser’s wife performed as a snake charmer in Hamburg’s Völkerschau at Hagenbecks Tierpark, essentially a human zoo. The Friedländer lithographic company in Hamburg made a chromolithograph of the snake charmer, the original of which has never been found. However, in 1955 this image was reprinted in Bombay, India, after being sent there from Ghana. It is unknown how exactly the image got to West Africa, but it is thought to have been taken from Hamburg by African sailors when they were in Germany. On its arrival in Africa, locals declared the depicted Maladamatjaute to bear a resemblance to Mami Wata. The image has since proliferated throughout the African continent as Mami Wata, the snake charmer. On Fait Ensemble suggests in a metaphorical sense that this image came from Europeans. This is done through the market performance of Papai Wata. Papai Wata, the consort of Mami Wata in Beninese traditional ceremonies, symbolizes the European man and is depicted in the video by being painted white.

Ato Malinda, On Fait Ensemble, 2010, Filmstill, courtesy: the artist

The exhibitionThe Divine Comedy: Heaven, Hell, Purgatory revisited by Contemporary African Artists curated bySimon Njami,MMK / Museum für Moderne Kunst, 21 March - 27 July 2014, Frankfurt/Main.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas