“These landscapes are extremely contemporary."

The young artist and photographer Mame-Diarra Niang who gives insights into Dakar’s changing landscapes. This is Ouakam, a neighborhood in Dakar. This construction is on the old runway of the Dakar airport. My intention with this series was to show the new face of Dakar. The last ten years have seen ever more new buildings and …

The young artist and photographerMame-Diarra Niang who gives insights into Dakar's changing landscapes.

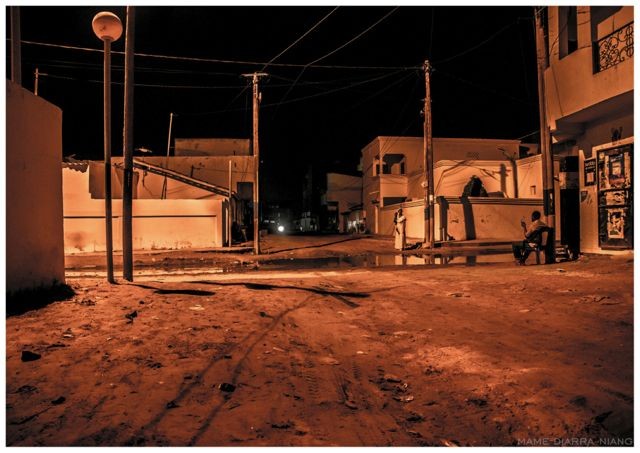

<figcaption> Sahel Gris © Mame-Diarra Niang

<!-- P { margin-bottom: 0.21cm; } -->

This is Ouakam, a neighborhood in Dakar. This construction is on the old runway of the Dakar airport. My intention with this series was to show the new face of Dakar. The last ten years have seen ever more new buildings and apartment blocks springing up here and there throughout the city, housing infrastructure that is architecturally quite limited—and this despite the fact that it was not our custom to live this way. We lived in our family homes or with each other. Now we are seeing a real search for individuality; individualism reigns in these kinds of dwellings. We have become consumers; we want to consume alone and in secret, to create a precise frame for ourselves. We are adopting a Western model which is in the process of collapsing—it’s not working in Europe, as everyone can see. We are starting to abandon things that worked for us until now because we envy what is happening elsewhere. I thought that this was an interesting topic to work on because it comes down to giving up the sky.

At the end of the day, we decide not to leave but to settle here. It is a kind of metaphor: we decide to settle into individualism, and even the sand used to make the bricks is sand that comes from this land. So we are witnessing a kind of choice: to wander, to roam, to walk, to flee, but at the same time to settle. It is a question of choice. You pass through, you trod upon the ground, or you build. In the process of this reappropriation of the space, or of this reappropriation of oneself—because the problem of living in large family homes here is precisely the loss of one’s unique profile—you no longer have a sense of yourself, you think with the others, collectively, and you no longer know where the boundaries of you are. In the end, what Senegalese or Africans living in the Diaspora can say is that they truly miss their families, but at the same time, when they come back to their countries, they need a certain degree of independence. And all of this problematizes this question, the frame you’ve imposed…When in Europe, we idealize Africa or this kind of community, but even if it has certain advantages, it also has its drawbacks. We all have to deal with this in our own way. And life in France is also idealized here.

Before construction even begins on the buildings, electrical boxes are put in place. So there are these whole plots full of little boxes. Here I was taking a walk on a plot like that. And it really felt like a cemetery. This thought occurred to me when I was wandering about—that was what I was doing when I took this series of photos, wandering aimlessly. Ultimately we spend our time trying to impose a frame and narrowing it. It’s almost as if we are adjusting to our own unique rhythm. In the end, because we are looking to live above others, life side by side with others will no longer be what it once was. It will be found in the cemetery, where we will all end up next to each other. Rambling around this landscape, I was really thinking about this idea, this loss of identity, about everything we’ve lost. And yes, we also have the need to be alone here, because the family can be a burden, society is a burden. So we have the need to build our own boxes, little boxes, each hidden from the others, above them, below them, but hidden in any case. And this amounts to a kind of death. My thoughts on this subject are still evolving. They are what led me to this photographic series, “Sahel Gris" (gray Sahel).

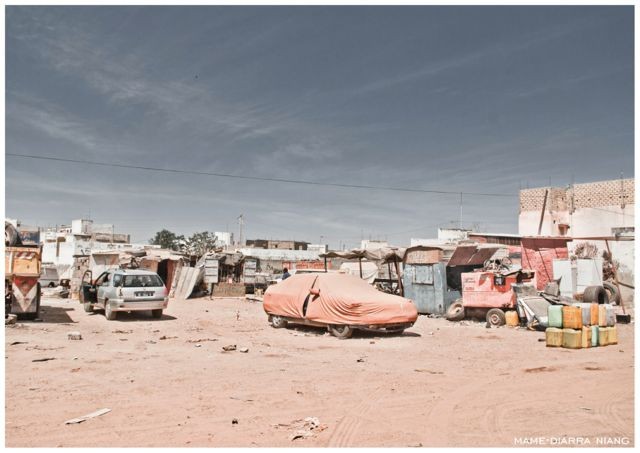

<figcaption> Sahel Gris © Mame-Diarra Niang

<figcaption> Sahel Gris © Mame-Diarra Niang

Dakar is becoming grayer and grayer because the bricks are made on site and the sand is just left there. Due to weathering, the sand used in the buildings turns gray; the landscape is gray because there is constant construction going on and everyone wants to keep going higher, always higher and higher. The highest rooftops keep being raised even higher. It’s as if the building were saying: “I haven’t said my last word yet, I may continue to grow, who knows?!” At the same time, the no man’s land areas where the horizon was very pronounced have been so built up that this horizon has disappeared entirely. All you can see is your neighbor. So even if you live alone, you’re still looking at each other, watching each other. I’m fascinated by this as well as frightened by it. I love concrete!

<figcaption> Thiayore obscura © Mame-Diarra Niang

This photo shows a house in ruins. This is the neighborhood where I grew up; the picture was taken in the middle of the rainy season. I came to Senegal when I was little. My father was very happy when he showed us our new house in this new neighborhood on the outskirts of Dakar. Today this neighborhood is in ruins. Due to lack of upkeep, because people have left—things have changed, other people live here now, it’s a different way of life. I have a very particular relationship to this neighborhood today. My work with these photos is also very personal. When I take photos, I am generally in this state of wandering, thinking about the paths that I take. And here, on these photos, you can see the paths that I always took, my way to school, my way home, my way to the store, places that I revisit, like an inventory. There you have it!

There is also something melancholy about it, because I no longer recognize this place. At the same time, it’s the Senegal my father never knew that I am photographing today. It’s precisely about this reappropration of the space.

<figcaption> Western Africa © Mame-Diarra Niang

This is the "Western Africa" series. It’s about taking stock, in a sense. The photos were taken when I was in a car, from the outside. I sometimes had to pass by the same object several times to get the right shot. I spent a lot of time in taxis during this period since I had to travel long distances and my days were very full. I was always either in a car or sitting in offices. My only escape was taking photographs and having to produce something. I always had my camera on me, aiming it out of the window, waiting for the right moment to release the shutter. I only ever saw what we were passing by through a lens; it was a pair of glasses, my vision, my work. To me these landscapes are extremely contemporary. They are like installations or stagings making up a real urban scenography where each object has its own life, its own utility.

So you could say that my work as a photographer provided the occasion for re-exploring all these places, for linking these different environments with each other: Paris, Abidjan, Dakar—these cities in which I was shaped as a person. This allows me to find an equilibrium. I don’t want to have to choose between these places. They all belong to me.

I have always been attracted to images, to photography, but I had not yet made a decision, a choice. I wanted to express myself. Photography allowed me to remain very reserved about what I felt. I didn’t have to put it into words; I could let people draw their own conclusions. From time to time I also made illustrations. There are always phases like that when I take lots of pictures and then I do illustrations or collages. This allows me to generate new ideas.

http://www.mamediarraniang.com

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas