There Isn’t One Way of Doing Things

24 March 2016

Magazine C&

7 min read

The free, expressive language of rhythm dancing connects Yorkshire clogs to West African steps. Pigments, introduced via trade routes, drawn from fantastical early Flemish painting, connect plantain to malachite and to an unstable idea of the exotic: Appau Junior Boakye-Yiadom’s layered practice is concerned with the possibilities that arise through slight gestures and incongruous …

The free, expressive language of rhythm dancing connects Yorkshire clogs to West African steps. Pigments, introduced via trade routes, drawn from fantastical early Flemish painting, connect plantain to malachite and to an unstable idea of the exotic: Appau Junior Boakye-Yiadom’s layered practice is concerned with the possibilities that arise through slight gestures and incongruous pairings. Spanning still images and found objects, videos assembled with archival footage, and installations ignited by live actions, Boakye-Yiadom’s works are a refusal of singular narrative, a celebration of multiplicity

Hansi Momodu-Gordon: P.Y.T. (2009) uses found objects and subtle gestures, as a pair of black penny loafers are held on tiptoes by a cloud of colorful balloons touching the ceiling. I am interested to know what the title stands for, but also in the role found objects play in your earlier works and how this is shifting in your more recent practice.

Appau Junior Boakye-Yiadom: It’s that Michael Jackson stance. I was trying to somehow encapsulate this iconic image and insert myself into that narrative. The title is from Michael Jackson’s song “Pretty Young Thing,” which relates to the work’s formal situation as well. The balloons can’t last forever and eventually the piece diminishes, so it was a reflection on that. I was very much aware of the space itself when making this piece, and that it spans from the floor to the ceiling. In more recent works, using video has meant moving away from objects and I just naturally started appropriating other found things. Whether it’s an iconic image or an object, I am attracted to things that already exist in the world. I still have that same approach, but with different material.

<figcaption> Appau Junior Boakye-Yiadom, Carmine Lake, 2015 from Baste on Narration series (2014-). Courtesy of the artist

.

HMG: Your ongoing series Baste on Narration (2014-) brings together references to Flemish painter Hieronymus Bosch, Russ Meyer’s 1976 sexploitation film Up!, and music from Travis Biggs’s 1976 rendition of the Steve Miller’s track “Fly Like an Eagle.” Can you describe how the installation comes together in a space, what led you to these source materials, and how they inform the work?

AJBY: There are two monitors, one on top of the other. The top one shows a clip taken from Up!, this black screen that unzips, so you are revealed and you’ve got somebody looking down at you. There is something about Russ Meyer’s cinematography that I find quite compelling. The monitor on the bottom displays a sequence of colors that were used in Hieronymus Bosch’s paintingThe Garden of Earthly Delights (1503–1515). In a voice-over I am narrating the colors of his palette to the backing track of “Fly Like an Eagle” by Travis Biggs.

Color was at the core of this piece. I was looking at The Garden of Earthly Delights and thinking about how it reflects early Flemish exploration, travel, and trade outside of Europe. The time it was created was quite an optimistic time. Everything was exotic: the food, the animals. It’s likely that Bosch himself wouldn’t have seen all these things firsthand, but he still depicts them in his painting. There are fantastical fruits and animals, and the people enjoying these earthly delights are of various ethnicities.

I have used a still from the ‘unzip’ scene in Up! in recent prints. The woman’s identity is quite ambiguous, and challenges the idea of the exotic. Most of the vegetables I collage her with were taken from East Street Market in London. Sweet potato, Scotch bonnet, plantain, okra: all these things are perishable goods grown outside of Europe and they all represent a color from Hieronymus Bosch’s palette. So there’s malachite, copper resinate, etc. Pigment was also introduced through trade and I was thinking about the new colors that would have been introduced during Bosch’s time.

<figcaption> Appau Junior Boakye-Yiadom, Untitled (Language Research), 2015. Video still. Courtesy of the artist

HMG: 4 minutes 6 of Conversation (2015) brings together your approach to archival research, process, and materials, using references from across different geographies. What was the evolution of this piece?

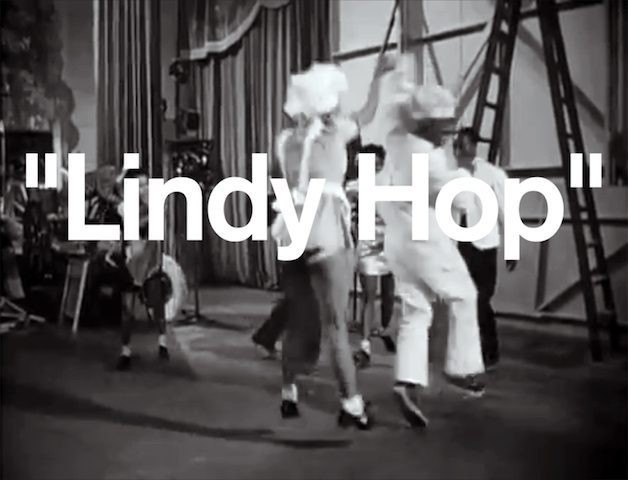

AJBY: I wanted to make a work reflecting 1960s male soul groups and their synchronized routines. I thought it was interesting how the gestures are always really slight and soft; it’s never too much. I knew I wanted to use a tambourine beat, which is a particularly 1960s soul sound, as I was so keen on incorporating sound right from the beginning. I searched through a lot of archival material and started looking at “No Maps on My Taps” (1979), featuring three tap dancers from the heyday―Chuck Green, Bunny Briggs and Sandman Sims―who in 1979 are looking back, saying, “Nobody’s interested in this now, things have moved on…”

This was one of the first times I incorporated archival material in my work and I wanted to make it my own. I was initially interested in finding footage of different dance traditions and looking at how they evolve within the language of that dance. However, I realized I had to think about other ways of talking about the Black transatlantic performer, because that is what the piece came to represent. The research led me from Yorkshire clog dancing to Harlem, New York, to West Africa. All of this is connected, part of a non-linguistic story. I’m interested in how non-literary forms are used for storytelling and the continuation of cultural heritage. The online availability of visual and moving image archives adds a new layer to this, with the possibility of appropriating stories and re-presenting them to new audiences. In certain cultures, you have dances that are passed down to different generations and slightly changed so as to keep them relevant. I was very interested in that particular history of sound and dance music.

HMG: Among your influences you have referencedThe Black Audio Film Collective and in particular the works ofJohn Akomfrah as well as Haim Steinbach’s shelf pieces. What is it about these practitioners that you feel an affinity with?

AJBY: I really like seeing a Steinbach. It’s just a reminder of how doing very little can be very effective. He creates this democratic plane that just holds as one. As for John Akomfrah, I’ve heard him talk about this idea of multiplicity and that’s what I am really interested in. Both artists manage to unify seemingly incongruous objects or ideas and to bring in different references, so that in a way their work becomes a truer reflection of society. Musically, the person/albumI listen to and who reflects what I want to do with my art is MF Doom ‘Mm.. Food’. The way he samples things, it’s this cut-and-paste that’s really appealing.

<figcaption> Appau Junior Boakye-Yiadom, P.Y.T, 2009. Installation image. Courtesy of the artist

HMG: What ideas are you exploring at the moment?

AJBY: I have been working on a few things around language, bringing together the Ghanaian Akan language “Twi”, New Years greetings “This time next year….” with Only Fools and Horses and Del Boy’s one-liner “This time next year, we’ll be millionaires.” I’m also starting to bring in more performance, narrations with visuals, and making that live. I feel that as an artist I want to show that there is not one single way, there is just multiplicity.

Hansi Momodu-Gordon is an independent curator, writer, and producer with recent projects at Autograph ABP and The Showroom (2015), and her book of artist interviews 9 Weeks is published by Stevenson (2016). She has held curatorial positions at the Tate Modern (2011-15), Turner Contemporary (2009-11), and the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (2008-09), and published writing on contemporary art with The Walther Collection, Rencontres de Bamako 10th edition, Frieze, and elsewhere.

from

In Conversation

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

‘To Treat Process with Care and Intention’: Favour Ritaro Carries Forward Important Curatorial Legacies

from

Archive

C& Highlights of 2025

The Museum of Black Futures