The Subversive Potential of Micro-Histories

For the first time of Venice Bienniale’s history the Belgian Pavilion exhibits the works of African artists – alongside with those of other nationalities, altogether examining the complex and hidden issues of colonial encounters and their aftermath. The logo of the Belgian Pavilion at this year’s 56th Biennale Arte di Venezia reminds me of those …

For the first time of Venice Bienniale’s history theBelgian Pavilion exhibits the works of African artists – alongside with those of other nationalities, altogether examining the complex and hidden issues of colonial encounters and their aftermath.

The logo of the Belgian Pavilion atthis year’s 56th Biennale Arte di Venezia reminds me of those little animated creatures popular in the 1990s. They popped up on the first gaming devices, with their big bellies, tiny feet and eyes all over. The logo also reminds me of a cell diagram of a simple organism as depicted in biology books. Besides, its black and white colour scheme is significant. I recall two sensations from my visits at the pavilion - a perception of monochromy on a grey scale and a reminiscence of a church layout induced by the building’s ground plan with its large centre area and the chapel like side rooms.

Logo of the Belgian Pavilion

The history of the pavilion and its relation to Belgian colonial history - in the context of a broader international perspective and of the Venice Biennale itself - are points of investigation in the researched-basedgroup exhibition entitled Personne et les autres. The title, meaning “no one and the others”, references a lost play by André Frankin, a Belgian critic affiliated with the Lettrist and Situationist International movements. Ten artists from four continents are taking part in the exhibition, and more importantly, for the first time in the history of the Belgian presence at the Venice Art Biennale artists from Africa are included. However, Belgium does not stand alone in breaking the tradition of selecting one or two artists to represent the country. Germany that shared this history of solo or duo exhibitions opened up its interpretation of a national contribution by inviting four international artists for the 55th Biennale in 2013, among them the South African photographer Santu Mofokeng.[1] Again this year, curator Florian Ebner presents four artistic projects by Olaf Nicolai, Hito Steyerl, Tobias Zielony, and Jasmina Metwaly & Philip Rizk.[2]

Initially planned as a temple for the arts, the Belgian Pavilion was the first foreign pavilion built 1907 in the Giardini, one of today’s two main exhibition areas of the biennial. Over the last century the building underwent several architectural alterations.[3] The pavilion’s relevance in terms of national representation found its visual expression in the addition of the coat of arms of Belgium in 1930 that still adorns the portal today. In conjunction with the geometrically arranged oculi on the stone grey windowless front the entrance recalls that of a fortress.

Outside view of the Belgian Pavilion 2015. Photo: Press Belgian pavilion

This year, the stronghold has been taken over as indicates the black pirate like flag with the imprint "Black Lives” by New York-based artist Adam Pendleton - a reference to the “Black Lives Matter” movement that arose from the protests over recent police violence in the US. The US-born Brussels-based artist Vincent Meessen who was selected to represent Belgium asked the curator Katerina Gregos to jointly develop a concept that would include multiple voices and viewpoints. They invited Mathieu K. Abonnenc, Sammy Baloji, James Beckett, Elisabetta Benassi, Patrick Bernier & Olive Martin, Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj, Maryam Jafri and Adam Pendleton to participate. All of them artists who share the interest of exploring complex and hidden issues of colonial encounters and their aftermath based on the concept of a pluralism of modernities.

Sammy Baloji, Sociétés Secrètes. 2015. Photo: Peters-Klaphake

Through their manifestations in micro-histories of forgotten relations or individuals in a perspective of entangled histories, the artworks in this dense and ambitious exhibition make references to political and artistic avant-garde movements like DADA, CoBrA, Situationist International, as well as Pan-Africanism, African Independence movements and Global ’68. Meessen’s three channel video installation One.Two.Three. is the centre piece of the exhibition. It reveals the largely unknown participation of Congolese intellectuals in the Situationist International by telling the story of a re-discovered protest song and its author, Congolese Situationist Joseph M’Belolo Ya M’Piku. The discursive and poetic exhibition not only creates references between the artworks in the space but also links to the main exhibition under the theme “All the World’s Futures”. While Sammy Baloji’s work Sociétés Secrètes connects to his copper sculpture The Other Memorial in the Arsenale, the continuous reading of Karl Marx’ “Das Kapital” only a few steps away in the Giardini’s main pavilion subtly resonates for example in M’Belolo’s statement: “Belgium had colonized Congo, but capitalism colonized Belgium.”

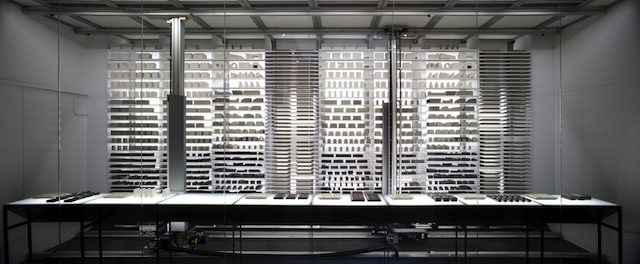

James Beckett, Negative Space, installation view. Photo: Alessandra Bello

The above mentioned feeling of monochromy stems from a factual dominance of blacks, whites and greys in the large installations of Pendleton and Beckett. Supported by the quasi natural tones of the plaster bones in Elisabetta Benassi’s tram station honouring M’Fumu; the shiny yet earthy copper in Baloji’s Sociétés Secrètes and faint colours of the historic aerial views of Lubumbashi’s colonial cityscape and the museum collections of flies and mosquitos in his Essay on Urban Planning; and the reduced colours in the prints of Maryam Jafri’s interrogation of iconic photographs of the African liberation. Yet, it really mirrors a subjective sensory impression resonating with the “archival impulse” at play. In returning to the metaphor of the cell, the exhibition can be seen as a fabric that carries some deciphered as well as lots of latent information on many of the world’s entangled histories bringing to light new narratives and subjectivities.

56th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia, May 9 - November 22, 2015

Katrin Peters-Klaphake is the curator at Makerere Art Gallery/Institute of Heritage Conservation and Restoration, Makerere University, Kampala, andco-initiator of the KLA ART project

References

Gregos, K. & Meessen, V. (Eds.) (2015). Personne et les autres. Vincent Meessen and Guests. Milan: Mousse Publishing

Foster, H. (2004). An Archival Impulse. In October 110, pp. 3-22.

The Venice Questionnaire 2015 #27: Vincent Meessen. In artreview

[1]The German contribution to the 55th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale Venezia 2013 - took place in the French Pavilion. Curater Susanne Gaensheimer showed works of Ai Weiwei, Romuald Karmakar, Santu Mofokeng und Dayanita Singh.

[2] Ebner further altered the German Pavilion considerably to overbuild the edifice's National Socialist architecture.“Starting from their varied reflections on the notions of ‘work’, ‘migration’, and ‘revolt’, the four artistic positions transform the building into a factory, into a vanished, virtual factory of the imagination, into a factory for political narratives and for analysing our visual culture.”

[3] In his historic analysis architecture theorist Bart Verschaffel concludes that the pavilion is again a “temple now not explicitly, or as allegory, but incarnated and hidden in sacred emptiness, divine whiteness, and wordless pure architecture.”

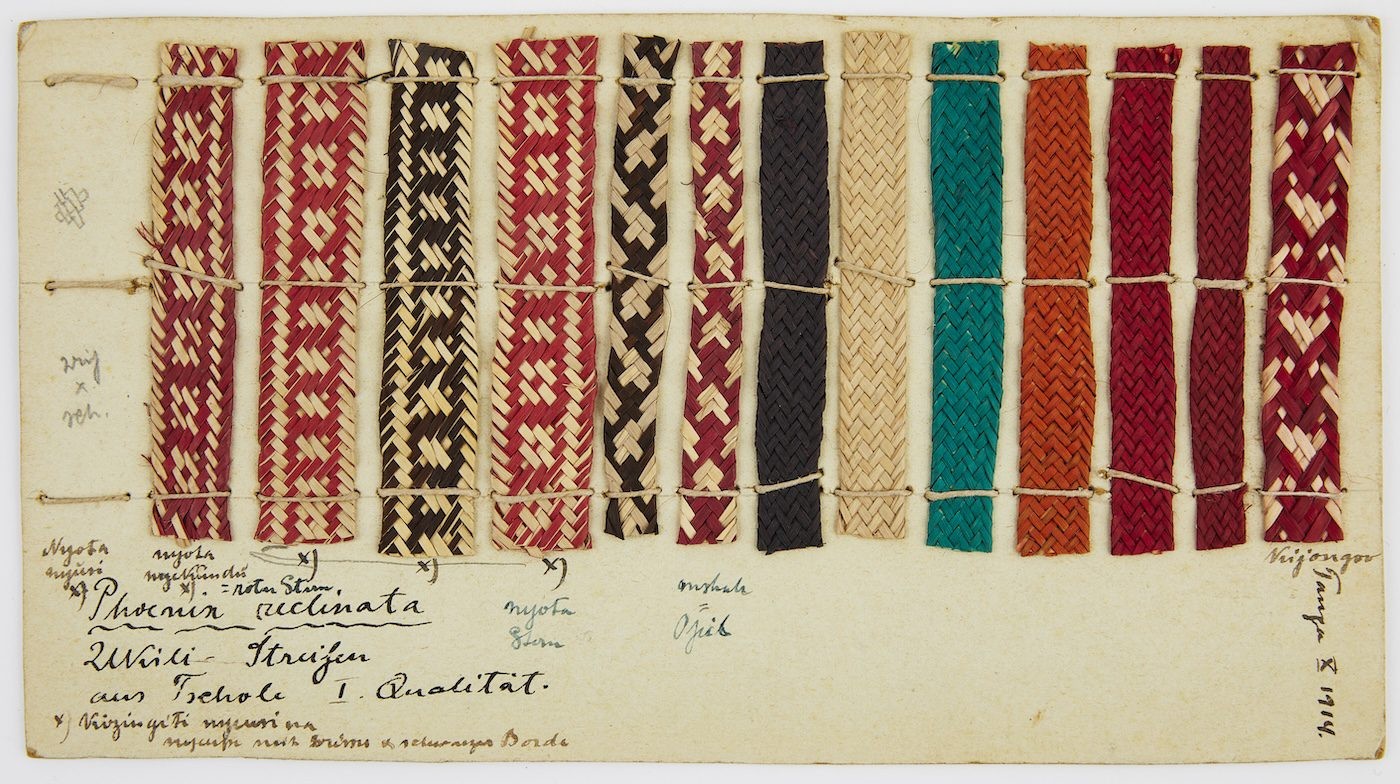

Colonial history

AMANI kukita | kung’oa - German and Tanzanian Perspectives on a Colonial Collection

Examining De/Colonial Traces Through Colonial Collections

Dekoloniale and C& Announce Berlin Residents 2024

Belgium

Baloji and the Art of Averting the Evil Eye

Otobong Nkanga Receives 2025 Nasher Prize