The New Church

In a speech to inaugurate the opening of his contemporary art space, The New Church, South Africa’s first privately owned museum devoted exclusively to art made after 1994, financier and collector Piet Viljoen conjectured how he and President Jacob Zuma were “connected through art, and specifically Brett Murray’s work”. “I was moved to start collecting …

In a speech to inaugurate the opening of his contemporary art space, The New Church, South Africa’s first privately owned museum devoted exclusively to art made after 1994, financier and collector Piet Viljoen conjectured how he and President Jacob Zuma were “connected through art, and specifically Brett Murray’s work”.

“I was moved to start collecting by his sculpture Africa, while our president was moved to ban his work,” said Viljoen. He was referring in the first instance to Murray’s JK Gross Trust-funded public sculpture on St George’s Mall in Cape Town, a bronze West African fetish figure sprouting garish yellow Bart Simpson heads. “At least we were both moved,” he added, making light of the recent imbrogliosurrounding Murray’s The Spear, a satirical painting that portrayed Zuma as Lenin, his penis exposed.

Viljoen’s road to Damascus moment as a collector happened in 1998. A former Reserve Bank analyst and currently the chairman of asset management company RE:CM, Viljoen was still working as a fund manager at Investec.

“It was the time of the IT bubble and Y2K,” he explained in a private walkthrough of his museum, a repurposed Victorian home built in 1890 on New Church Street in the suburb of Tamboerskloof. Challenging the prevailing orthodoxy, he presented a talk at an Investec conference that “lambasted” the hype around the new digital economy. “The visual thread in my PowerPoint presentation was Murray’s sculpture.”

Afterwards someone told him that art dealers Andries Loots and Fred de Jager were selling a miniature bronze model of Murray’s work. He set off in search of it. “I saw a whole bunch of other stuff that blew my mind,” recalled Viljoen. “That’s where it started.”

Murray’s model, which is the size of gold Academy Award, sits on a shelf adjacent some of Norman Catherine’s freaky oil on wood mini-sculptures in Viljoen’s office. Nearby, on the carpeted floor, is a garish pink figurative sculpture by Michael MacGarry. The polyurethane and industrial foam was shown on MacGarry’s solo exhibition The Other Half: Past and Future Now, held at Stevenson gallery in June. I initially mistook the Roland drum kit on the opposite end of the room for an artwork too. Not so. Viljoen uses it to practice his rock riffs. Yip, Viljoen has his own man cave.

For a while now there has been whispered talk about a big name collection opening a private art museum in Cape Town. Joburg collector Gordon Schachat, PUMA chairman Jochen Zeitz and English collector Charles Saatchi have all been mooted as candidates. In the end, Viljoen, who dismisses talk of art as an investment, quietly got on with the business of finding a space, signing the title deed, contracting an architect and placating angry neighbours.

While admittedly prompted by a “selfish” motive – “I wanted to see my work, it was all in storage” – his new venture is, like the man, studied and calm, also generous and playful. A text work by painter Georgina Gratrix installed at the entrance pithily summarises his attitude: “Art is very, very, very … serious.”

As part of his commitment to treating art very seriously, Viljoen, whose passions also extend to cycling, invited artist Penny Siopis to sift through his 480-piece collection and organise a representative display for the museum’s opening.

Siopis’s selection includes a number of her Stevenson Gallery stable mates, notably new abstractionist painter Zander Blom, installation artistDineo Seshee Bopape, sculptor Nicholas Hlobo andLynette Yiadom-Boakye, a London-based figurative painter of Ghanaian descent. She has also included her own work, the short film Obscure White Messenger, an impressionistic collage of found images and Verwoerd assassin DimitriTsafendas’s biographical statements.

“Yes, my collection is focussed on a couple of galleries,” responded Viljoen to a query about the small circle of galleries – including Goodman Gallry, Whatiftheworld and SMAC – whose artists are represented on his show. “But those galleries look after their artists’ careers much better than of the other galleries, so it is no accident.”

Elaborating on how she worked with the constrained albeit blue chip sampling of contemporary production in Viljoen’s collection, Siopis stated: “My point was to try draw out what I perceive to be the heart of Piet’s collection, which is really his interest in the human subject. My interest was not so much the obvious identity stuff but rather the kind of works that speak about the human subject through forms that manifestly require engagement from the viewer.”

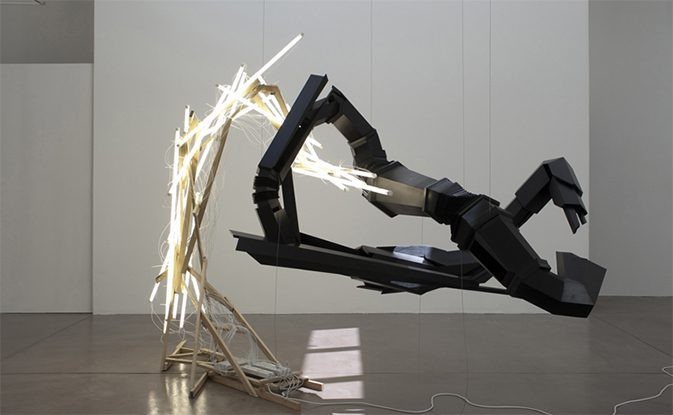

The exhibition, which is titled Subject as Matter, includes a number of works by Walter Battiss. It is the only concession to a pre-1994 practice engaged with ideas of contemporaneity and selfhood. Wim Botha’s recently completed white neon and wood sculptural installation, Time Machine, is undoubtedly the show’s standout piece. A dynamic integration of competing black and white forms, the impossibly asymmetrical work is displayed in a retrofitted double-volume space at the rear of the museum space.

“After being a bit uncertain, I loved seeing that work when I went to the opening,” said Botha, whose work was recently included on The Rainbow Nation, an exhibition of three generations of sculpture from South Africa, at Museum Beelden aan Zee, The Hague. “Such an unlikely object.”

“The work reminds me of a challenging project I once set students where they had to draw a human being using only the lines that could be made with a ruler,” writes Sioipis in an accompanying catalogue.

The New Church, which will host Siopis’s exhibition for the duration of summer, is open to the public by appointment only.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and co-editor ofCityScapes, a critical journal for urban enquiry. He lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025