The Line between Analysis and Insult

17 November 2015

Magazine C& Magazine

9 min read

Egyptian cartoonist, scriptwriter, culture critic, podcast creator and artist Andeel was born in the northern delta city of Kafr al-Sheikh in 1986. He moved to Cairo and became a professional cartoonist as a teenager, working for various national newspapers. He has since co-founded Tok Tok, a comics quarterly, and launched the podcast Radio Kafr al-Sheikh …

Egyptian cartoonist, scriptwriter, culture critic, podcast creator and artist Andeel was born in the northern delta city of Kafr al-Sheikh in 1986. He moved to Cairo and became a professional cartoonist as a teenager, working for various national newspapers. He has since co-founded Tok Tok, a comics quarterly, and launched the podcast Radio Kafr al-Sheikh al-Habeeba. He now works for online media platform Mada Masr, and the first film he has written as sole author, Zombie Go Zombie, is about to go into production. Jenifer Evans is the culture editor at Mada Masr and co-founder of artist-run space Nile Sunset Annex. Andeel is her husband.

Jenifer Evans: Sometimes your cartoons make a point, but sometimes they're more conceptual or focus on a mood or feeling ―those ones can be a bit puzzling to editors. Can you describe your style a bit, and give an example of both types?

Andeel: Generally, my inking style or color palette gives almost all my work a visual signature. I emphasize lines with thick strokes the same way I do with an idea when I'm speaking, yet the shapes and masses are a bit wobbly and badly finished like most of the things I'm surrounded by in Egypt.

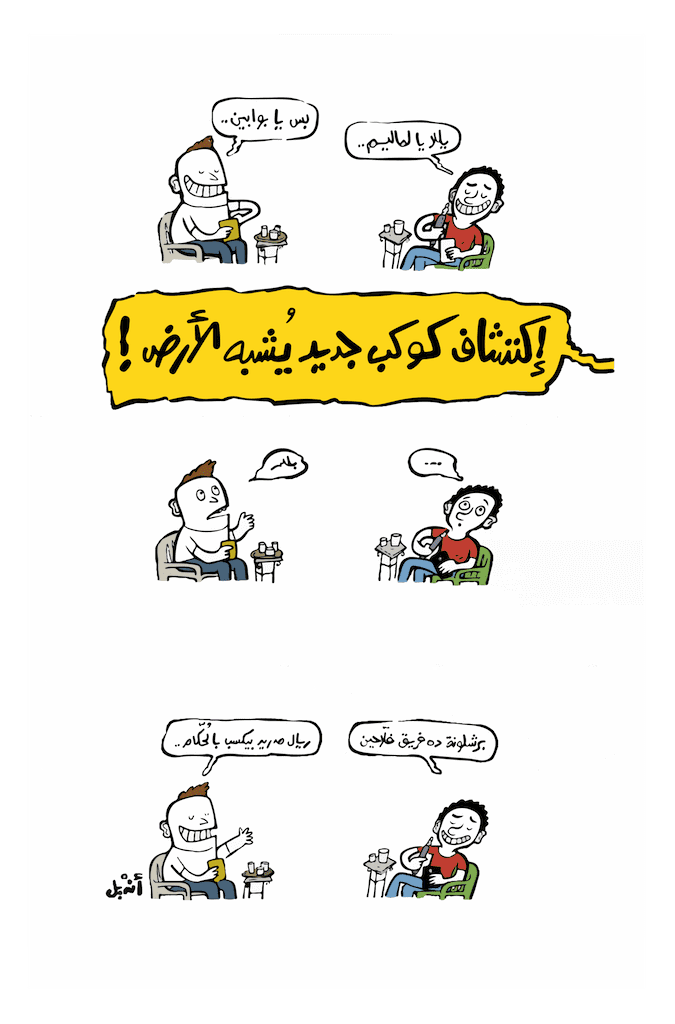

Sometimes I make predictable cartoons that react to news, like this one:

<figcaption> Andeel, originally published in Mada Masr, 2015. Courtesy of the artist

Dude 1: "You're a bunch of low-class football supporters."

Dude 2: "You're doormen."

Announcement: "A new planet similar to Earth has been discovered!"

Dude 1: "Barcelona is a team of peasants."

Dude 2: "Real Madrid only wins by bribing referees."

And sometimes I make cartoons that open discussions people might be unprepared for, or might not know exactly what I’m trying to say, like this one:

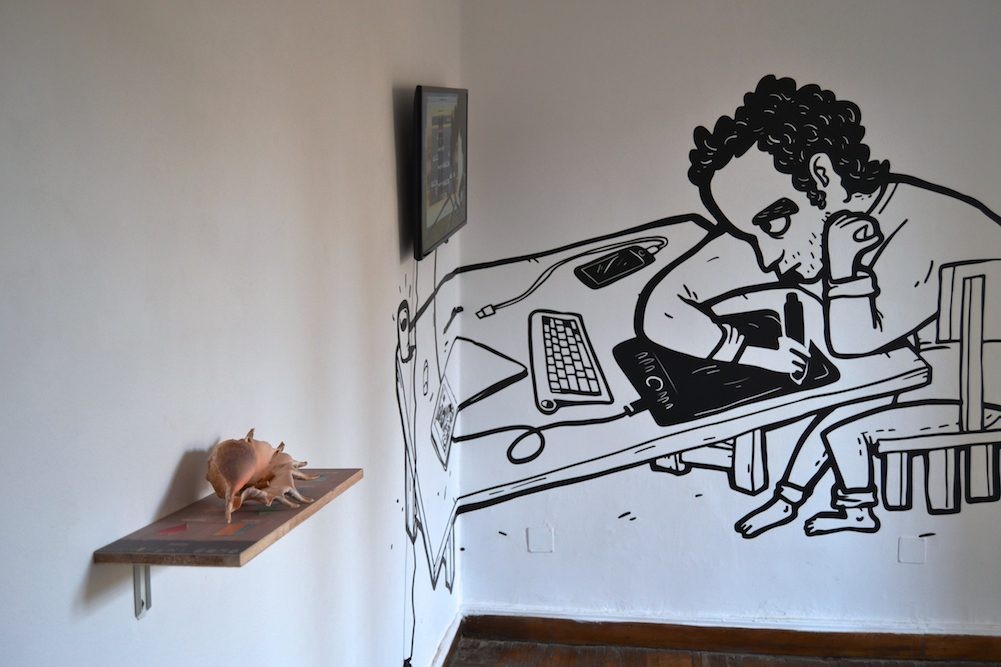

<figcaption> © Andeel, originally published in Mada Masr, 2014

Guy 1: "Those gay people are funny, bro..."

Guy 2: "Yeah man..."

JE: What was your model for constructing a cartoon when you started out, and how did you develop your current process ― drawing with pencil on paper, taking a photo of the drawing with your phone, then "inking" it in Photoshop?

A: My first job was at Al-Dostour [a privately owned national weekly], and I was working with people older than me. I learned how to do cartoons the classic way, meaning pencil on paper, then inking with a brush or marker. We even sometimes corrected mistakes with white correction pens, or cut and pasted parts of the drawing. The medium ― poorly printed newspapers ― controlled the aesthetics a lot. Sometimes that was exciting and sometimes boring.

JE: I can’t imagine you using a paintbrush!

A: I wasn’t very attracted to those traditional solutions ― I always found computers a lot more exciting and empowering. In 2011 I started using a digital drawing tablet to ink and color my work, and it changed my style dramatically and opened new horizons. I like RGB colors, and feel they belong to this era of history. I also like how a computer allows me to elaborate the drawing and make decisions as I go instead of having a strict plan I just execute.

JE: How is it different working for print and digital, which is mainly what you do now? Does it change the way you think about the cartoons?

A: Yes. Firstly the readership is different. Demographically, generation-wise and even politically. I feel freer to express myself in a way I find more relevant, less reactionary, and more fun and playful.

Technically, online cartoons look and behave a lot like cartoons in newspapers, but I try to push their function and to benefit as much as possible from the new medium. Sometimes I make them extra long to make readers scroll to the point, like here.

Or I play with the titles and what people expect when they open the link, like here:

A cartoon that won't be understood by the main character in it

<figcaption> Andeel, originally published in Mada Masr, 2013. Courtesy of the artist

JE: You get annoyed with European and US journalists for focusing on the sexy issue of freedom of expression over anything else, like the actual work you’re producing or other curtailed freedoms, like freedom of movement. It seems ignorant at best to insistently ask you about this when your relationship with the “West” has been characterized ― until this month and your trip to Cologne ― by visa rejections. Is there anything you wouldn’t make a cartoon about?

A: I’d find it very problematic to use the power of satire against a group or person already oppressed or suffering. I was deeply and ideologically in dispute with the Muslim Brotherhood when they were in power, but felt uncomfortable making fun of them when they were being arrested and executed left and right. I make fun of the Muslim majority’s religiosity sometimes because of ideas I have about organized religion as a method of advancing society, public interpretation of morality and collective failure, which I see a lot in the generic Islam of Egypt (and many other Muslim-majority countries), but I’d never make fun of Egypt’s Copts, even though they’re very similar, and would probably behave similarly if they were the majority. Right now they’re under so much pressure I can’t justify picking up on them, like a lot of minorities in many places in the world.

JE: How does your writing, which manifests on social media but also as a culture writer for Mada Masr and a writer of TV and film scripts, complement the cartoons?

A: One thing I like about cartoons is that they work very well when based on a strong opinion. I enjoy the fact that my work isn’t only about being able to draw stuff. Social media has encouraged people to express opinions and share them, so for me, it’s a good chance to start conversations about important things people don’t really want to talk about in a society where many opinions are oppressed. As for criticism, I think there’s a big void in culture writing in Egypt for a lot of reasons. I try to look into what makes good works good, and bad works bad. I find the choices and challenges artists must go through to produce art here, navigating the economy, politics and major cultural complexities (identity, religion, the idea of liberty and tolerance, etc.), very exciting. For me writing about art is a self-teaching process ― as a person who’s interested in producing art ― before it can be a discussion opener with whoever’s interested.

JE: What about film and TV? The first movie you’ve written as sole author, an apocalyptic film set in your hometown of Kafr al-Sheikh, is being directed by Ahmad Abdalla.

A: I think of it as a natural extension of a comedy practice. I learned a bit about traditional scriptwriting working on little projects, and I enjoy challenging the commercial requirements for success ― decided and enforced by a complicated network of investors, other “creatives” and general common culture ― when working in mainstream entertainment. I love the freedom artistic creation gives you to express your deepest, irrelevant personal issues, but sometimes really cool work can come out of a project in which you’re pretending that you’re not doing that at all. Abdalla is a filmmaker famous for his experimental, art-prioritizing career, but we’re trying out making a movie that will hopefully be ― I mean, of course it will be ― extremely popular.

JE: You’ve also been going in the opposite direction — lately you’ve been making forays into the contemporary art world. You’ve been helping out at Nile Sunset Annex, and we invited you to do a collaborative show with Kareem Lotfy that happened in March, the same month your billboard collaboration with Hassan Khan was shown at Sharjah Biennial. What are the good and bad things about doing contemporary art stuff?

A: I used to have a negative relationship with contemporary art. My first encounter was through foreign-funded art institutions in Cairo after I moved here. I didn’t really feel properly introduced or welcomed, and the work I saw felt alien to me — I couldn’t relate to the language or what was being said. Later I became friends with contemporary artists and had interesting conversations about it. I also saw more diverse practices, like Nile Sunset Annex, which I found a lot more chilled and less institutionalized and nervous. I started finding a lot of inspiration in contemporary art for other things I produce, and then I was even tempted to try and produce my own contributions to it. You can digest an artwork because of how it feels or the way it has a presence, rather than an obvious point or “message.” Hassan knows exactly what he’s doing, and seeing his work for the first time was one of the things that helped me create a different understanding of contemporary art. The stages we went through to develop the billboards were very interesting. Even though it looks like a piece with a very specific idea, the conversations behind it were sometimes enjoyably vague. We spoke about things that didn’t seem to have any connection except through the piece. We discussed the aesthetics and specifics, like the composition or the characters’ clothes, as well as existential worries and fears. I remember Hassan saying: “Children are weird, children and monkeys are weird!” It was exciting to be collaborating with Hassan and Kareem during the same period because they’re such different artists. While Hassan’s work seems to be weighed with a golden scale, Kareem’s brains are all over the place. He didn’t seem to mind what direction the work took, yet always had a very strong response. His ability to react felt very spontaneous and fluid, which contrasted with Hassan’s very precise, structured relationship with the work.

Read more from

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Read more from

MAM São Paulo announces Diane Lima as Curator of the 39th Panorama of Brazilian Art

Naomi Beckwith Unveils Core Artistic Team for documenta 16